Tucson mother Jessala Grijalva can usually get what she needs for herself and her three children, but she’s found some surprising exceptions.

Leer en español: Invertir desde el principio puede evitar resultados horribles

The first in her family to finish college, she earned a bachelor’s degree in government and public service with highest honors from the University of Arizona last May and recently was accepted at Notre Dame, fully funded for a Ph.D. in political science.

But the last year has been a struggle. She lost her campus job in February 2017 and could not find work that would allow her to complete her studies. Money got especially tight in August when she stopped receiving unemployment checks.

She’s working now, for AmeriCorps, but what she needed most, in addition to a little cash to make it to the end of the month, was help with child care.

She thought she could get help through a federally funded program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, since she was doing so much to improve her life while also caring for her children.

Not so.

Arizona has the some of the strictest guidelines in the nation for TANF.

Even though Grijalva and her children live well below poverty level — which is $24,600 annually for a family of four — she couldn’t get help because her ex-husband pays $1,020 a month in child support for the children she’s otherwise raising alone.

“It was really confusing,” she said. “I had them explain it to me, about why I don’t qualify, and I was told Arizona has a special rule.”

She does receive some help with food through SNAP, which stands for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, as well as with health care through Medicaid. The $214 per month from SNAP covers about 40 percent of her food budget.

To cope, as she studied, looked for work and completed internships with Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild and U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva, she resorted to leaving her children home alone sometimes. Likes others she knows, she bought a cellphone for the eldest, who turned 13 in January.

“A lot of my friends are getting their kids cellphones so it’s easy to check in on them,” she said.

Despite living under the poverty line, Jessala Grijalva and her three children were denied cash assistance through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program.

Federal millions shifted

Covering the basics is the type of primary prevention Arizona needs most, said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.

Instead, families are often required to complete a lot of programming and classes without having other supports put in place, Wexler said. That can compound family stress and “make everything worse.”

TANF — which is distributed as a block grant, meaning states decide how to use the funds — is intended for families in transition. Job training, child care and cash assistance are the main objectives, but in Arizona, most of the money goes to the state’s Department of Child Safety to support foster families and adoption services, and to provide child care to families already involved with DCS.

The share of TANF money moved to DCS grew by 67 percent from fiscal year 2010 to fiscal 2015 as the number of children DCS removed from their homes swelled.

As access to child care for poor and low-income families dropped from 16,200 families in 2009 to an all-time low of 3,700 in 2014, the cases of neglect reported to DCS grew from 9,850 to just under 20,000 during 2015.

Arizona spent $469 million in TANF funds in 2015, says the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Of that, 8 percent went to the original objectives of job training, child care and cash assistance. Just under half went to DCS.

The state also reduced its cash assistance and hunger relief funding under TANF from $77 million in 2009 to $28 million for fiscal year 2016, and its employment services dropped from $13 million in 2009 to $6 million in 2016.

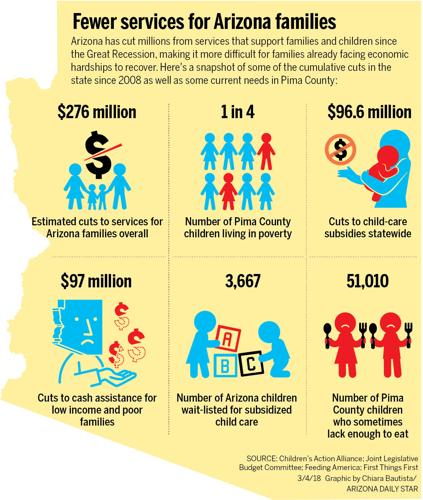

Click the graphic to enlarge

The waiting list for Pima County families who need child-care help but who are not involved with DCS is dauntingly long — Grijalva was told last year that 2,000 families were ahead of her.

TANF isn’t the only funding option to help Arizona families pay for child care. The state gets about $125 million per year in federal Child Care and Development Funds, which provide most of what the Department of Economic Security uses in its child-care programs.

As part of this, Arizona is required to offer what’s called maintenance of effort and matching funds — which means the state cannot claim a $37 million portion of the total grant without also spending $30 million of its own dollars on child-care–related activities.

That wasn’t a problem until the Great Recession. When the economy went south, lawmakers reduced spending and continued to do so until 2012, when all general fund spending on child care in the state was eliminated. In 2015, some of those funds were restored, with the state counting on about $30 million a year from First Things First, a 2006 voter initiative created to help Arizona children during their first five years.

Don't miss a story → Sign up for our Foster Care newsletter

First Things First is already spending that money, mostly on improving the quality of child care and providing child-care scholarships.

Even so, nearly 3,700 children are on the child-care waiting list statewide.

Help with food, housing

In El Paso County, Colorado, tackling poverty is considered a key to preventing child neglect — and its officials use TANF as one of their central components.

Here’s how it works: Caseworkers from the county’s child safety system and those providing TANF services collaborate with a focus on helping the family, not conducting an investigation. They know that families qualifying for TANF or Medicaid have an increased likelihood of entering the child safety system because of economic stress and hardship.

To reduce the chance of abuse and, especially, neglect, they try to quickly get families help with food, housing and health care.

And if a family is reported for possible abuse or neglect, they look to see what benefits the family is receiving. If the family is lacking something critical, those services are put in place as quickly as possible.

“The same things that lead people to get benefits like TANF or child care, those same things cause child welfare issues,” said Marian Percy, the deputy director of the county’s Children, Youth and Family Services. “It could be generational, or be due to a lack of education, (or to) domestic violence or substance abuse.”

The challenge is helping families without making them afraid, said David Berns, who set this approach in motion when he came to El Paso County as director of the Department of Human Services in 1997. He focused on reducing the number of kids in out-of-home care while improving safety for children at risk.

“Caseworkers weren’t being trained to be family-centered,” he said. “Now, the training is focused on engaging with the families and how to create less damage and have them experience a lot less trauma.”

One thing he noticed time and again is that most families coming into the child-safety system are poor.

“It’s not because poverty causes abuse and neglect but because families that are low on economic resources cannot weather the storms the same way a middle-class household can,” he said. “To keep kids out of foster care, you can’t just put in safety plans. You have to address the real poverty issues.”

Caseworkers focused on creating plans with families and found that one positive change often rippled out to cause many more. If they addressed housing and helped with child care, for example, they found people could work more and set up transportation.

Colorado county sees poverty at root of neglect

“We don’t ever want to deal with a parent having to have their child placed (in foster care) due to poverty,” said Cheryl Schnell, director of adult and family services for El Paso County’s Department of Human Services.

The idea was to avoid the costs that come later: adults with long-term substance abuse and high medical costs, kids in foster care and the juvenile justice system.

“If we invest our strategies in things that prevent horrible outcomes, it’s not only cheaper, but then families can start contributing back into the system,” Berns said.

The changes won bipartisan support as several thousand people dropped off the county’s welfare rolls during the first five years.

Pima County used to have a similar program, but it didn’t last long, said Chris Swenson-Smith, former division director for child and family services at the Juvenile Court Center here.

Families eligible for, or already receiving, cash assistance were also to receive intensive prevention services. The program, Family Connections, was headed by the state’s Department of Economic Security and included partners from DCS, Medicaid, TANF and a job training program.

Arizona stopped funding it in 2009.