Editor's note: This story was originally published in May 2018.

It happened fast, but then, these things do.

One minute, Arizona women’s basketball coach Adia Barnes was on the road recruiting; the next, she was spending the day in Longview, Texas, visiting her estranged and ailing father.

That day would change both of their lives.

Over the next 10 months, Adia Barnes got to know her father, Pete, for the first time, moved him to Tucson and watched as his health rapidly declined. Pete Barnes, a longtime NFL linebacker, died May 3 in Tucson hospice care after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. He was 72 years old.

Adia Barnes said the caretaking was “rewarding and hard.”

“I’m glad I did it,” she said. “I look back and I told my sisters this: If we wouldn’t have done something, he would have just died.”

People are also reading…

Arizona coach Adia Barnes reflects on Wildcats' memorable tournament run, calls Aari McDonald best player in school history

A phone call — and a shocking discovery

To understand the relationship between Adia Barnes and her father, one has to go back nearly 38 years. She was just 3 years old when her parents, Pete and Pat, divorced. Her mother eventually married another man, Bruce McRae, and Barnes and her birth father drifted apart.

Barnes went to the UA, became a basketball star and spent 10 years playing overseas. She would talk to Pete on the phone periodically.

“Was it hard because he wasn’t a part of my life and didn’t take care of me? Yes, it was. But I wasn’t angry about that because I had a good life,” Barnes said. “I wasn’t mad about anything. I wasn’t bitter, or didn’t feel like I missed out, or waking up every day thinking I don’t have a dad, because when Bruce came into my life, he was my dad.”

Last year, Barnes received a phone call from Lee Thomas, one of Pete Barnes’ old teammates with the Chargers. Pete was living in Texas and struggling to survive. Upon arriving in Texas, Adia Barnes learned her father’s landlord had been charging him multiple times per month. Pete, his memory slipping, didn’t remember that he had already paid.

“He was paying for telephones and paying thousands of dollars a month for stuff,” she said. “It was insane.”

Adia Barnes moved her dad to another apartment, leaving his clothes and much of his belongings behind.

“I’m sure there was paperwork, but I wasn’t going to go through anything,” she said. “I was just so upset about the situation. I bought him all new clothes — it wasn’t worth taking. Everyone was taking advantage of him.”

The move was temporary. Pete Barnes couldn’t be left by himself. He wandered off frequently. Eventually, Adia’s sister, Candace, took Pete in.

Adia and her sisters, Candace and Maisha, began researching their options and talking to doctors, former NFL players and health-care workers. The goal: to get their dad into the NFL’s 88 Plan, which grants retired NFL players with dementia around $100,000 per year for medical and custodial care. The plan is named after John Mackey, the Hall of Fame tight end who died in 2011 after years of living with dementia.

Barnes took over control of her father’s life right as she was preparing for her second season coaching the Wildcats.

“For me, it was necessary,” she said. “He needed it. I wasn’t just going to stand there and not do anything.”

In November, Adia moved her father to Tucson and admitted him into the Copper Canyon Alzheimer’s Special Care Center. Two days after he arrived, the Barnes family received welcome news: Pete was now a part of the NFL’s 88 Plan.

“It’s hard with all these transfers, but I don’t know the solution,” said Arizona coach Adia Barnes of the current state of college basketball.

'I was his baby'

In the beginning, Adia Barnes couldn’t understand how her father was left alone.

The more she talked to those close to him and the more she learned about him, however, she began to understand. Pete Barnes was independent and stubborn, and he certainly wasn’t going to take someone’s charity.

Still, he moved out of state with his daughter. Adia says her dad was tired and knew he needed help.

And then, this: “He was sad that he didn’t take care of me. He was sad he didn’t have a relationship with me. I think that’s why he came.”

Those who know the 41-year-old coach best say they weren’t surprised that she took the lead.

“Adia is always trying to help someone, no matter the circumstances in her own life — with a family to care for and a program to run, she always takes on the next thing,” UA assistant coach Morgan Valley said. “To me, this is normal; she tends to carry a lot. She’s taught the girls a lot of lessons. Life happens; you move on. In the end she still has to get up in the morning, go to work, take care of her son, and coach. It’s pretty impressive.

“She didn’t have to do this, but the fact that she did shows who she is.”

Adia got to know her father during the final five months of his life. And he was introduced to a new cast of people: Barnes’ husband, Salvo Coppa — also a UA assistant — and their son Matteo.

They talked about football and shared stories. Pete Barnes even came to watch Adia coach a UA game — and the Wildcats won.

Pete was often confused and forgetful. But he never forgot his daughter.

“He knew who I was,” she said. “I was his baby.”

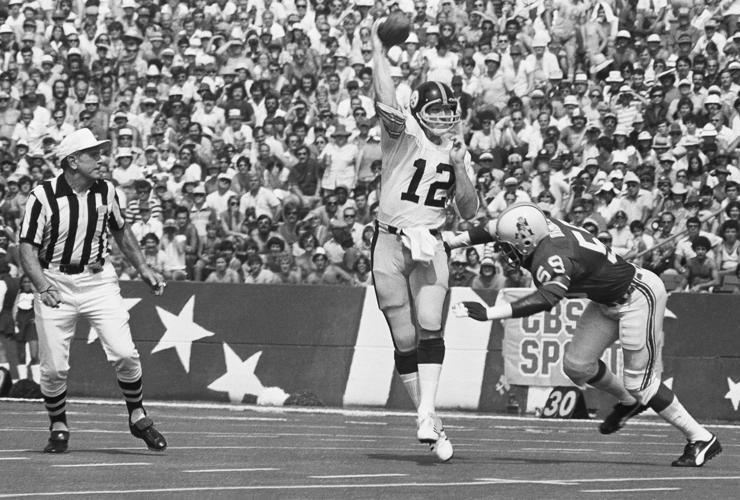

During that time, Barnes learned much about her estranged father. Pete Barnes was a tremendous athlete who earned All-American honors in both baseball and football while at Southern University. The Houston Oilers took him in the sixth round of the 1967 draft, and gave him a $45,000 signing bonus to choose football. He played 11 seasons with the NFL’s Oilers, Chargers, Cardinals and Patriots.

Pete was also a smart and savvy businessman who owned and sold several apartments in coastal San Diego — near Mission Bay High School, where his daughter became a basketball star — long before it became trendy.

He walked away from his business after his playing days were over. Asked why, Adia Barnes offered a two-word reason: “brain damage.”

New England Patriots linebacker Pete Barnes chases Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw in first quarter of play at Foxboro, Mass., Aug. 28, 1977. The pass was incomplete. (AP Photo)

'He must have known'

Adia Barnes and her sisters think they know what led to their father’s premature death: the same violent collisions that made him a name in the NFL.

Pete Barnes played 142 games across 11 pro seasons. Who knows how many concussions he suffered, how many bone-jarring hits he delivered and received, or how much damage was done to his brain? The Barnes family believes Pete’s Alzheimer’s was the result of CTE, a degenerative brain disease often found in athletes and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma.

A 2017 Boston University study examined the brains of 202 deceased former football players, 111 of whom had played in the NFL. All but one of the former NFL players’ brains had CTE. Over the years, hundreds of former football players have demonstrated symptoms of CTE, including odd or forgetful behavior, or developed early-onset Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease. Some, like Junior Seau — the most popular player in Adia Barnes’ hometown — kill themselves rather than endure a slow descent.

Pete Barnes’ death came quickly. He was moved into hospice care 4ƒ months after relocating to Tucson, and died two weeks later.

At Pete’s request, the family donated his brain to Boston University to determine whether he had CTE. Results can take as long as eight months.

Adia said her father “wanted to help other players.”

“He must have known (he had CTE),” she said. “Sometimes he would get frustrated that it wasn’t clicking, like there was a miss in his synapses or something. He would be sharp about certain things and then be like, ‘You know, I’m having a hard time. Don’t ask me about that.’ He was trying to search for stuff and there was a space that was just gone.”

Earlier in May, Adia Barnes traveled to Pete’s hometown to formally — finally — deliver her father home. The UA coach was amazed at the number of people — she estimated in the thousands — who attended a viewing and celebration of life for the man she had just started to know.

Barnes is proud of what she was able to do for her father but wishes they had had more time together.

“I didn’t think he was going to decline so fast,” she said. “I think God did this for a purpose, for me to spend the rest of his life with him.”