Authors’ Note: Over the course of a decade, from 2006 to 2016, members of a Latino-led movement in Maricopa County waged an energetic resistance against Sheriff Joe Arpaio, discriminatory policing by his agency, and the laws and policies that enabled it.

Maricopa County residents of Latino descent, including U.S. citizens, felt targeted by Arpaio’s shock-and-awe immigration-themed sweeps of neighborhoods in which deputies arrested undocumented immigrant drivers and passengers and provoked terror and outrage in the Latino community.

The resistance sought justice in the halls of Congress, the voting booth, the public square, the streets and the courts. Maricopa County Latino drivers and passengers brought a class action racial profiling lawsuit against Arpaio and his agency. A federal judge ruled that Arpaio and his deputies had engaged in unconstitutional policing.

Arpaio lost his election for Maricopa County sheriff after 24 years in that office. The former sheriff was subsequently convicted of criminal contempt of court only to be pardoned by then president Donald J. Trump, who later lost Arizona in 2020 to Joe Biden. The resistance is credited with helping transform Arizona into a battleground state.

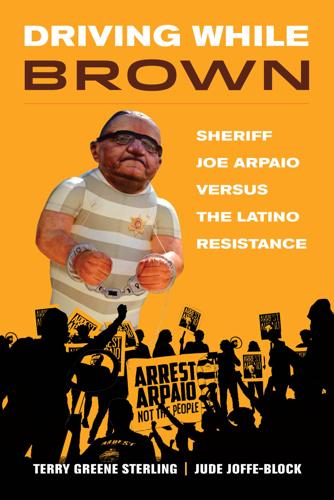

This adapted excerpt from the new nonfiction book, "Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio versus the Latino Resistance," by Terry Greene Sterling and Jude Joffe-Block (University of California Press), recounts a 2012 scene witnessed by the authors outside the federal courthouse in Phoenix.

The scene features Carlos Garcia, a former Tucsonan who is now a Phoenix City Council member. A graduate of Desert View High School, Garcia was born in Sonora and lived for several years as an undocumented immigrant in Tucson — an experience that shaped his unique brand of activism.

Excerpt from "Driving While Brown: Sheriff Joe Arpaio versus the Latino Resistance":

“Arrest Arpaio! Not the people!” Carlos Garcia chanted with other young protesters outside the courthouse.

It was July 2012. Inside the courtroom, Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio testified that his deputies had not racially profiled Latino drivers and passengers.

But for now, Garcia didn’t want the media to report only on “attorneys coming to save the day.”

Garcia was a leader of the Puente Human Rights Movement. The group’s volunteers were already nationally known for organizing colorful and daring street protests that aimed to keep the pressure on both Arpaio and the Obama administration, which so far had failed to deliver immigration reform during the president’s first term.

At 29, Garcia was at odds with some older members of the Latino-led resistance who trusted that institutions – like the courts – would help them get rid of Arpaio. They also believed Democrats would one day deliver immigration reform.

Garcia believed people vulnerable to deportation should have the tools to defend themselves and not rely on institutions.

The U.S. Supreme Court had just allowed a key provision of SB 1070 to take effect. It required local police to inquire about the immigration status of people they suspected of being undocumented.

The court’s ruling only cemented Garcia’s reluctance to count on the judiciary. Nor did he trust Democrats. Deportations under Obama far outpaced the deportations of the Bush administration.

Garcia had already felt the sting of the Obama deportations. One cousin had been deported. Another cousin was sitting in a federal detention center awaiting an immigration court hearing.

The Obama administration had publicly sided with immigrant rights advocates by having its justice department conduct a civil rights investigation of Arpaio, by challenging Arizona’s SB 1070 in the Supreme Court, by suggesting ICE use “prosecutorial discretion” when deciding which deportation cases to pursue, and by revoking Arpaio’s 287(g) partnership that had once allowed his office to enforce federal immigration laws.

But nevertheless, ICE officials were still quietly scooping up undocumented people who had landed in Arpaio’s jails.

So, when Arpaio’s racial profiling trial broke for lunch, Puente launched the group’s boldest action to date.

Standing in the searing July sun, four Puente members outed themselves to the media as undocumented immigrants and then sat down at a busy intersection just east of the federal courthouse.

Each protester sat on one corner of an enormous poster carpeting the hot asphalt.

The poster read: No Papers No Fear: Sin Papeles y Sin Miedo.

The protesters were doing exactly what most undocumented people wanted to avoid. They put themselves in the dangerous position of getting booked into Arpaio’s Fourth Avenue jail where ICE agents might choose to deport them.

One protester, Leticia Ramirez, hugged her young daughter before her imminent arrest. “Give a kiss to your brother and your papi, OK?” she told her child in Spanish.

Minutes later, Phoenix police took all four protesters into custody.

Since all four protesters had clean records. Garcia hoped ICE would use its “prosecutorial discretion” to not deport the immigrants if Puente kept the pressure on and the media amplified the story.

As it turned out his strategy was on target.

Three protesters were released from jail that afternoon. The fourth, Miguel Guerra, was transferred from jail to ICE custody. It was a harrowing night. Garcia stayed up with Guerra’s family.

Puente alerted the media and eventually pressured ICE to release Guerra.

The daring act was so well covered by news outlets that it could not be ignored by the public. Garcia and the protesters had clearly delivered their message.

Being bold had paid off.