For more than a decade, Raytheon Missile Systems has been making missile interceptors that destroy their targets in space.

Now, the Tucson-based company is adapting those capabilities to develop small, disposable military satellites that give ground troops on-demand views of their locations.

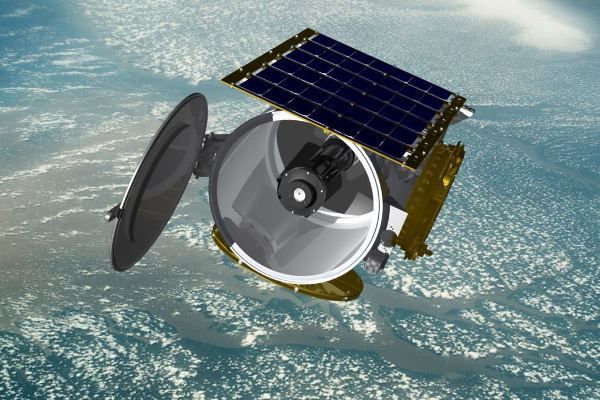

Raytheon has modified some of its manufacturing lines in Tucson to produce relatively inexpensive satellites for a program called Space Enabled Effects for Military Engagements, or SeeMe.

The program, managed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, aims to give ground forces the ability to get high-resolution satellite images of the battlefield via their smartphones or other hand-held devices, within 90 minutes.

In contrast to military spy satellites as big as a bus that cost $1 billion or more, Raytheon’s “nano satellites” weigh about 50 pounds, are roughly the size of a 5-gallon paint bucket and have an expected base price tag of less than $500,000.

The SeeMe constellation was designed to use some two dozen satellites, each lasting 60 to 90 days in very low-Earth orbit before falling out of orbit and burning up.

DARPA’s request for SeeMe designs caught the attention of the folks at Raytheon’s sprawling missile plant at Tucson International Airport, which was looking for new markets.

“We determined we could easily translate our capabilities and technologies into the emerging small-space market,” said Randall Gricious, business-development lead for Raytheon’s small-satellite business.

It turns out that small satellites are very similar to missiles — they have similar subsystems including power, propulsion, guidance, avionics, communications and sensors, Gricious said.

In Tucson, Raytheon Missile Systems already builds two “kill vehicles” for ballistic missile interceptors designed to destroy enemy missiles in space — one for the Ground-based Missile Defense system and another for the Standard Missile-3, part of the mainly ship-based Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense system.

In 2015, the company completed a $9.2 million expansion of its Space Systems Operations factory at its airport plant.

Funding interrupted

Whether the new effort translates into actual business is still uncertain.

Raytheon won a $1.5 million SeeMe design contract in 2012, and two other companies were awarded similar contracts in 2012 and 2013.

DARPA’s SeeMe program lost funding a couple of years ago, but it is being kept alive by Raytheon and other contractors with some DARPA support.

Despite the loss of future funding and launch delays, Raytheon still hopes its SeeMe satellite prototype will be flown into space sometime next year.

The company already has adapted some missile technologies to space vehicles.

In 2009, it modified a high-resolution synthetic aperture radar from a tactical missile to both the Indian Chandraayn-1 and NASA Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter missions that detected ice on the moon, Gricious noted.

The interest in small military satellites comes as the commercial market for small satellites is booming.

Spaceworks Enterprises, an Atlanta-based space engineering company, predicts that launches of satellites in the 1-50 kilogram class (up to about 110 pounds) will double to more than 400 annually by 2022.

The global small-satellite market is estimated to be worth $2.2 billion this year and is projected to grow to $5.3 billion by 2021, with a compound annual growth rate of more than 19 percent, according to the research firm MarketsandMarkets.

Backlog of launches

One major factor that could cut into those forecasts is the limited availability of launch services.

Much of the growth in small-satellite deployment is being driven by small, modular satellites known as CubeSats, which were developed by scientists at California Polytechnic University and Stanford University in 1999.

Launches of CubeSats — which are assembled in roughly 4-inch cubic units — and similar small satellites accelerated in the mid-2000s and peaked in 2014, but last year launches dropped due to limited launch capacity and launch failures.

A couple of dozen companies are working to bring new small-sat launch vehicles to market including launch-industry giants like Orbital ATK and startups like Vector Space Systems, which announced last week it would build its headquarters and rocket production facilities in Tucson.

Several launch failures from late 2014 through 2015 contributed to the growing backlog of small-satellite launches, Spaceworks said.

Failures of launch provider SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket last year and again on Sept. 1 has put launches of many small satellites — including Raytheon’s SeeMe prototype — on hold while SpaceX investigates.

Raytheon’s Gricious said the company’s SeeMe satellite is scheduled to ride into space aboard a Falcon 9 along with the primary payload — an Asian communications satellite — and 86 other small satellites.

The launch has been pushed back several times for various reasons, including the Falcon 9 failures, Gricious said.

“Our best guess for launch is first quarter 2017,” he said, adding that the prototype recently completed final testing.

The other two companies that were awarded SeeMe design contracts, California-based Millennium Space Systems and NovaWurks, a Northrop Grumman tech spinoff, are also awaiting prototype launches, though Millennium tested its craft in a high-altitude balloon flight in late 2013.

DARPA program manager Jeremy Palmer said though the government program formally ended in 2014, the agency has been monitoring the progress of Raytheon’s satellite closely and the prototype will be stored until a launch vehicle is available.

Flying commercial

A space-policy analyst said the Pentagon has been looking to increase satellite-level intelligence capacity because existing military satellites — including huge surveillance satellites built by defense giants like Boeing and Lockheed Martin — can’t handle demand.

A system like SeeMe would put satellite data into the hands of troops on the ground, but the Pentagon planners have their eyes on the fast-evolving commercial small-sat industry, said Brian Weeden, technical adviser to the Secure World Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit promoting sustainable use of space.

“My guess is all this commercial activity, which is starting to solve some of these problems, may have played a role in why this program didn’t get the funding,” he said.

Indeed, during comments at a conference on small satellites last year, the commander of the Air Force Space Command said the military will move slowly and look to the commercial sector for help with its small-sat programs.

“When the commercial sector starts investing money and starts proving capabilities, just like in the launch business, we’re going to walk into that with eyes wide open and figure out how to take advantage of those capabilities,” Gen. John E. Hyten said in a keynote speech at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics/Utah State University Small Satellite Conference.