Fifth-graders wear angel costumes as they walk in procession through Barrio Viejo. Other elementary students are dressed as peasants or shepherds.

A few get special jobs, like carrying the manger that holds baby Jesus or knocking on doors to ask for shelter. When the children sing carols, their voices are joined by the neighborhood’s faithful.

The night is Las Posadas, a Mexican Christmas tradition where a community comes together to act out Mary and Joseph’s search for a place to bear Jesus. The pageant is put on as a collaboration between the students at Carrillo Elementary School and their neighbors in Barrio Viejo.

The troupe of children marches through the neighborhood. Tradition dictates that the first four houses deny the party a place to stay. The fifth home opens its doors to the crowd.

The barrio takes pride in the tradition, which has been hosted by the elementary school since 1937, with brief interruption by COVID. It’s one of the few remaining examples of the vibrant culture that once defined the neighborhood.

Since Las Posadas began in the barrio, the original community has endured powerful waves of displacement. First, in the late ‘60s, when the city declared the area a slum and removed over 700 mainly Mexican-American, Indigenous and Black residents to build the Tucson Convention Center. Then again, years later, when people with more means identified the neighborhood as desirable, thanks in large part to its character: adobe homes, ceilings lined with saguaro ribs, old trees. The barrio is history you can touch.

Star girl Irasema Baldenegro walks through the school playground as the procession begins for the 85th Annual Las Posadas celebration at Carrillo Elementary School.

Today, few adults who participated in Las Posadas as children remain in Barrio Viejo. Many of their peers have been driven out by some of the highest property values in the city. Those who have persisted usually choose to open their homes to the procession, homes which have often been passed down from their ancestors. They might attend services at the Catholic San Cosme Church, where people who used to live in the barrio return as pilgrims, for worship. El Minuto Cafe has had to raise its prices, but that’s where you might encounter people sitting together and catching up with their neighbors, the way they used to when Elysian Grove Market was run by a local Latino family. But that property is a single-family home now.

As newcomers buy properties in the barrio, they are faced with the question of how to be good neighbors, and to whom that applies. The stakes can feel higher when the new face is not just a family, but a business, like a restaurant or coffee shop, that will attract even more people into the neighborhood as visitors.

These groups of newcomers may appreciate the barrio’s charm, but not understand the fraught, multicultural history that created the neighborhood’s beauty, or see how that history survives today in residents like neighborhood association president Pedro Gonzales, who was removed from his home by urban renewal in the late ‘60s.

Exo Roast Co., an upscale coffee shop, came to Barrio Viejo in February. Before them, boutique retailers already entered the area, like The Coronet and 5 Points restaurants, and venues like La Suprema. “I have reverence and respect for the neighborhood,” said Exo co-owner Amy Smith. “People have told me, ‘Well, it’s already been gentrified.’ That didn’t sit well with me.”

As the fabric of their community changes, barrio residents are hoping to keep their history and culture intact. But investors coming into the area have long held the power to transform the neighborhood: in whose image will they build the barrio’s future?

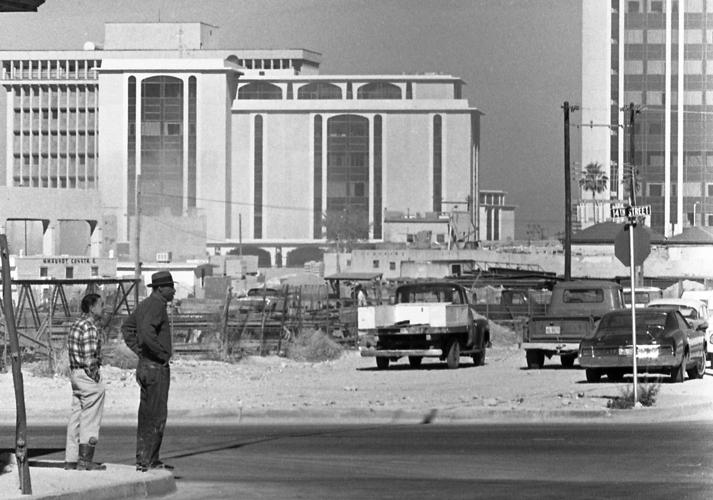

A couple of gentlemen stand on West 14th Street (later became Cushing Street) and possibly South Church Avenue as construction continues on the Tucson Convention Center on December 4, 1970.

Urban renewal remakes Barrio Viejo

Development has long dictated the fate of Barrio Viejo. In the 1960s, the city received federal funding to demolish a part of the neighborhood called El Hoyo (or, the hole, named due to its low bearing and tendency to flood). In its place the city would build the Tucson Convention Center in an attempt to revitalize downtown. The city, through the Pueblo Center Redevelopment Project, displaced Gonzales and his family from their house just before Thanksgiving 1967.

“The experience taught me what it means to take something personally. When someone takes your car, your purse, $10 straight out of your pocket. That’s just things. They took my home, displaced my family,” he said.

Gonzales is quoted in Lydia Otero’s book “La Calle,” a history of Barrio Viejo and how it was destroyed by urban renewal. Stories of residents of the barrio open each chapter.

Lydia Otero, author of "La Calle"

“La Calle” tells the story of the barrio like this: In the ‘60s, city planners perceived the dense, vibrant communities just south of downtown as blight. The barrios were predominantly Mexican-American and had been for nearly 100 years. Despite reports that extolled the charm of the historical houses, the racial makeup of the area caused city officials, bankers and powerful groups like the Committee on Urban Blight (COMB), to label the area as slums.

In 1942, less than 3% of homes were in need of repair, Otero cites. Despite that, over the course of the next two decades, city officials failed to provide services like trash removal to the area. Bankers denied the barrio’s homeowners and landlords access to loans to maintain or improve their properties. “By the mid-1960s,” Otero writes, the barrio “had become synonymous with ‘old,’ ‘dilapidated,’ and ‘dangerous.’”

COMB, which spearheaded the redevelopment project that would eventually displace 735 people to build the TCC, “hoped to populate the downtown area with a new breed of people: ‘Change the environment and people will want to live in high density apartments in the downtown,’” according to Otero’s book.

Today, people see what remains of the barrio as valuable. Sites of community have been reimagined. A former schoolhouse has been turned into affordable housing for elderly residents. An old bakery is now a single family home. Traditional Mexican details, like colorful plaster facades, courtyards and niches, are priceless heritage, belonging both to the Mexican-Americans who built the barrio and the newcomers who now occupy it.

Patrons enjoy the small patio at Exo Roast Co., 196 W Simpson Street.

Exo Roast Co. moves in

The neighborhood’s history was exactly what drew Amy Smith to locate Exo’s second shop in Barrio Viejo.

“When we first were looking at places … I [didn’t] want to move into a strip mall on Speedway, or the northeast side,” she said. “We wanted to find a place to bake in, and a historic space. Because so much of it has been razed, there’s not a lot of options for historic space.” The location the co-owners chose is one of the few properties that is commercially zoned in Barrio Viejo.

Like many newcomers, Smith honors the history of her property with fidelity to its details. Intention is omnipresent, from the absence of wifi to locally-sourced ingredients to sparse, elegant design. The interior is exquisite, with the hand-spread white plaster signature to the neighborhood, rustic wood details, pristinely-laid brick floors.

The decor is highly curated. Exo’s furniture is mostly a type called Ranch Oak, which was made by the A. Brandt company in Texas during the mid-century period. Smith’s partner sources the furniture second-hand, scouring Craigslist, consignment stores and the deep corners of the internet to score. On the entire central wall, next to the counter, there’s only one framed piece of art: a poster from the Marfa Agave Festival. “If it looks like it’s a living room, it’s because mine is basically empty right now,” she said.

Amy Smith, owner of Exo Roast Co., poses for a photo inside the second location of the shop at 196 W Simpson Street.

Construction complicating the entrance to Exo’s original location, on East Sixth Street and North Sixth Avenue, motivated Smith to open a second location.

The majority of Exo’s Barrio Viejo location is office and event space, where Smith plans to extend Exo's community collaboration programs and host workshops and salons discussing books.

These events, she imagines, will be accompanied with food and drink, including alcoholic beverages — a point some barrio residents are unhappy with.

In an industry with small profit margins for coffee and even smaller profit margins for food, selling alcohol is an economic choice for Exo. Smith’s goals — to do more than break even, to give back to the community, to continue paying her staff a living wage, to feel financially stable herself during a lengthy city construction project — are much more possible with the ability to sell liquor.

“But why here?” Gonzales asked.

Pedro Gonzales, chair of the Barrio Viejo neighborhood association.

Urban Removal

Barrio Viejo today is very different from the neighborhood that was partially razed to make the convention center. Its history, beauty and proximity to downtown make it one of the most desirable neighborhoods in Tucson. Few have been able to maintain a foothold in the neighborhood through many stages of evolution — from the bohemian artists who laid the groundwork for gentrification in the ‘80s to the late-stage investors like Diane Keaton who have renovated historical properties for a tidy profit.

Gonzales is one of those few, with a house on the micro block of South Elias Avenue.

Walking down the street, you can visibly tell which homes more likely belong to multigenerational families, and which to newcomers. The renovated houses have been maximized for resale value with additions and expensive-looking walls or fencing. Some details are reminiscent of those at Exo: hand-spread white plaster, antique wooden doors.

Gonzales has witnessed generations of predatory practices — investors trying to buy low and sell high.

“I get postcards from realtors constantly asking us to sell our home. My neighbors get them, too,” he said. “I’ve asked them to stop sending them but they never do.”

“Zopilotes, I call them, vultures,” he said. He knows of people who keep close track of the city’s property tax records. If a family fails to pay property taxes, anyone with the cash to pay them off can place a tax lien on the property. If the family then fails to pay the lien back, the investor who has paid off the property tax gets to keep the property, for pennies on the dollar.

In nearby Barrio Anita, the beloved Anita Street Market was victim of a tax lien last year. Investors were almost able to acquire the property by paying off just over $100,000 of taxes, which accumulated, Gracie Soto said, because her abuela trusted the wrong accountants. Nearby properties are evaluated to be worth two or three times that amount.

Other families have lost their home in Barrio Viejo because the parent who owned the place died, and no individual child was able to buy out the other siblings’ stakes in the property. They sell and split the proceeds equally to use in their daily lives elsewhere in Tucson.

Lalo Guerrero Elderly Housing, 124 W. 18th Street.

Through decades of attrition, the original community who built the history that makes Barrio Viejo special is now easily outnumbered by newcomers. One place the barrio holds onto is the church San Cosme, where former Barrio Viejo residents can attend services. The interior of the chapel is humble: parishioners sit in vinyl-covered seats you might associate with a public school auditorium, not fancy pews.

“When you say this coffee shop is beautiful,” Gonzales asked me, “To who is it beautiful? Not me,” he said. While Exo plans to host events, they don’t resonate with Gonzales. “My community is simple. It’s about our family, our faith, our food, talking to people,” he said.

Gonzales finds Exo’s restaurant license, which permits the sale of alcohol, disrespectful. “Barrio Viejo is not here at your disposal,” he said. “They want to sell liquor across the street from a school, a block away from a church.” His grandchildren attend Carrillo, like he did. His family goes to that church. “It’s very, very disrespectful to us,” he said.

After losing so much of his community to displacement, to Gonzales this feels like another outsider coming in and dictating what they want to do in his space, without considering its impact on him or his community. “To me, [Exo is] doing the same thing the government has done,” he said.

In addition to opposing the restaurant license for its proximity to a school and church, Gonzales is skeptical about parking. He says the residential neighborhood doesn’t have enough space — especially since the arrival of places like 5 Points, La Suprema and now Exo. He wants to make sure the Carrillo parking spots are reserved for school use, to make sure elderly residents won’t be forced to park blocks away or in another neighborhood altogether.

For her part, Smith is excited to be close to a school. She wants Carrillo teachers and guardians to feel comfortable in her coffee shop, and to support the school.

“My husband and I are former educators,” she said. “We do truly respect this community and want to be a part of it. A bunch of Carrillo teachers came in and I cried and whooped and hollered,” she said.

“I kept our coffee affordable because I wanted them to be able to afford it.” When asked about the restaurant license, she insisted: “I’m not going to sell alcohol during the school day.”

Gonzales sees the task of advocating for his community differently. He got involved in community organizing decades ago, with the encouragement of Father Arsenio Carrillo, the beloved namesake of Carrillo Elementary.

Gonzales’ vision was to start a land trust for the barrio. The trust would be able to purchase houses in the area and sell them at an affordable rate, with the stipulation that when the property owner moved on or died, the property would be sold at the same low price to someone else in the community.

While he was able to organize his community, start the trust and eventually become the neighborhood association president, the funding from the city to implement the trust never came through. He felt betrayed by the city once again.

He and the neighbors he speaks for have mistrust for the government. They’ve felt marginalized and let down too many times. The latest of which came with Exo: despite Gonzales and the other neighborhood officials sending a letter to city council, begging them to reject the license’s application on the grounds of its proximity to the school and that overflow parking would displace residents’ parking spots, Exo’s restaurant license was approved on March 22, in a bulk vote along with the other six licenses and four event permits that had been submitted since the last meeting.

Moving forward

Exo has addressed Gonzales’ concerns about their business: to mitigate parking overflowing into the barrio, they have bought seven parking spots in a nearby lot. They will not be selling alcohol during school hours.

But the pattern of development still hits close to home for Gonzales. When investors said the barrio would be more valuable as a convention center, he was removed from his home. When investors said the barrio would be more valuable as a residential neighborhood, the people who came in didn’t look like him, didn’t connect with him like the people they replaced. To him, the narrative is consistent: the fate of his home has been decided by outsiders who felt entitled to do what they wanted in the area.

Growing up, his neighbors would ask him — not just once — how his day was, if there was anything they could help him with, or if they needed a favor. They’d yell at him if his DIY projects were too loud, then invite him over for a meal. He still tries to maintain this kind of community, one where people rely on their neighbors and are a meaningful part of each others’ lives.

I saw this community in Barrio Kroeger Lane, adjacent to Viejo but with the highway cut straight through. There, people were constantly coming up to Doña Josefina Cardenas, their neighborhood association secretary and co-founder of the community organization Favor Celestial. Cardenas was mentored in community organizing by Gonzales.

One neighbor asked her, in Spanish, when the city was coming for the twice-annual Brush & Bulky trash collection. Another asked if he could give her an enchilada (when he couldn’t, because his wife had already given the food away, he brought cellophane-wrapped pastries instead).

During our interview, a third neighbor asked her for extensive counsel about the neighborhood dogs and how to handle an unfair landlord. A more recent addition to Barrio Kroeger walked by, her dogs on a leash, in silence. Gonzales has seen a similar pattern in his own barrio. “Newcomers, they’ll say hi once, and then a year later, they’ll say it again,” Gonzales said.

Gonzales still tries to be a part of the barrio in the style he was raised, even to newcomers like his next-door neighbor Charles. When you’re on the phone with him, people in the background call out to him in Spanish. He opens his home every year for Las Posadas.

Kroeger Lane is starting to face some of the gentrification that Viejo has already endured. While newcomers often come in with the intention of being good neighbors, Cardenas said: “Good intentions are important, but more important is the strength to see them through.”