Editor's note: This story contains descriptions of child abuse, coercive sex and domestic violence.

For her first 22 years, Sarah Kiser’s thick hair stretched down past her knees.

People would accidentally sit on it. The strands would gnarl up into painful tangles. The ends always felt dry and unhealthy because she couldn’t cut it, not even a small trim, she said. Her head throbbed from frequent migraines due to its weight. It would get caught in car doors, hairdryers and once even a vacuum.

She hated it. But Kiser said the length of her hair was never her choice, much like the rest of her life when she was part of a religious sect called “The Message.” She now calls the group a “cult.”

“Everything I did was controlled based on rules that Branham set in place for women to follow,” Kiser said.

The late Rev. William Branham was a preacher who gained fame in the 1950s for his faith healings. He died in 1965, but the religious sect he started, called "The Message of the Hour," has millions of devotees worldwide who consider Branham their prophet, according to a rough estimate from a Message nonprofit organization called Voice of God Recordings. Branham’s sermons, which were recorded before his death, have been criticized for containing misogynistic rhetoric and doctrine.

Kiser, 26, of Virginia, was raised in a Message church called Faith of the Apostles in Arkansas. She said the church was “very misogynistic” and “more cult-like” than other churches in the fringe Christian sect.

A photo of Sarah Kiser's long hair while she was in The Message. Kiser said her friend had painstakingly curled her hair into ringlets.

“I was raised to believe that the only thing that I was supposed to do — that I was meant to do — was to be a wife and a mom,” Kiser said. “The entire system was rigged against women.”

The church discouraged her from pursuing a career or college education. She was not allowed to move out of her parents’ house until she got married because she needed to be under the “headship,” or authority, of a man at all times, she said.

The dress code for women was strict, and if they didn’t follow it, they were “shamed and reprimanded” for tempting men to lust, Kiser said. Skirts below the knee or longer, and shirts with high necklines and at least short sleeves were required. No pants, bra straps, panty lines, makeup, painted nails, high heels, tight-fitting clothes or short hair. Branham ridiculed women for wearing makeup and said a man had a right to divorce his wife if she ever cut her hair.

From a young age, Kiser had been strong-willed, sassy and independent, but The Message took that away from her. When she was herself, church members chastised her for not acting like “a young lady,” she said. She said her personality was “squashed.”

“(Branham) said that women were supposed to be meek, quiet women ... and they weren’t worth a good, clean bullet,” Kiser said. “Women were just not respected.”

Sarah Kiser is pictured in her home in Bristol, Va., Aug. 16, 2024. She wears a pair of bright pink pants and a tank top that shows her shoulders, clothes she would have been barred from wearing in her former fundamentalist church. Under the faith she used to follow, "The Message," she had to always wear long skirts to cover her figure so she did not temp men to lust.

Branham’s influence

Branham said in 1959 that he was not “a woman hater,” nor was he against Message women. He was “just against the way modern women act.” In that same sermon, he said young women who get drunk with older men and then come home to their husbands are “not worth a good clean bullet to kill them with.”

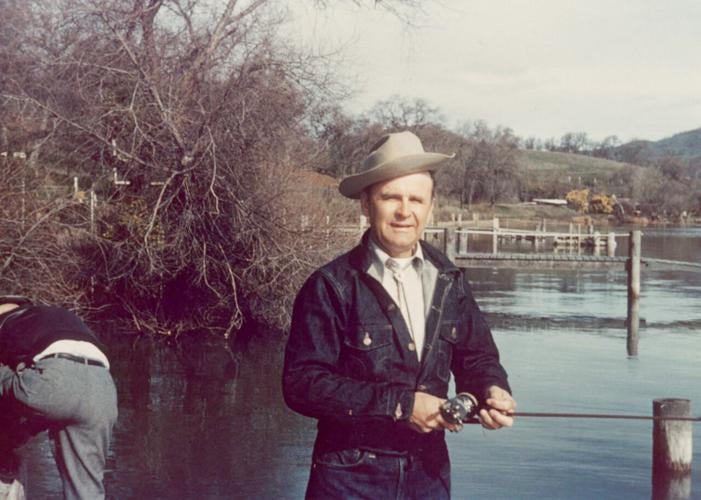

Rev. William Branham fishes in this photo from Voice of God Recordings' archives.

Kara Younce, 28, who grew up with Kiser at Faith of the Apostles, confirmed that the church was a very controlling environment for women. Younce said she left because she didn’t want her daughter to be forced to follow a dress code that Younce herself didn’t believe in. She didn’t want her daughter to be made to think that she was less than a man, something she said Branham instills in Message believers.

“I read a quote from (Branham) where he said something along the lines of if she wears inappropriate clothing or smokes cigarettes, the husband should beat her with a board. The other one was him saying that women were designed by Satan,” Younce said, paraphrasing sermons that Branham gave in 1958 and 1965. “I was shocked because no one had ever told me that he said those things.”

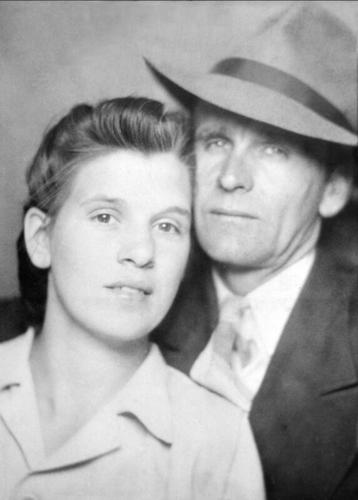

Rev. William Branham and his wife Meda Branham in the late 1940s. Branham married Meda after his first wife died in 1937. Branham preached that a man's wife should be his "sweetheart," not a "doormat." But he also preached that a man who lets his wife smoke cigarettes "don't love her or he'd take a board and blister her with it."

“I had been raised to think that he was God’s prophet, and I didn’t think that someone who was speaking the words of God to me would say such terrible things about women. So then I was mad I guess at the ministers for not telling me this.”

Branham's teaching that men are the leaders of the home and church left Kiser with no agency, which made her an easy target for abuse, she said.

Kiser said her father was physically abusive. As head of her household, Kiser's father whipped her with belts when she was a child, she said. Once, he split her lip open after backhanding her across the mouth while wearing a ring, Kiser said.

Her father said in a brief phone interview that he was not interested in commenting on those allegations, but said, “Sarah said a lot of things just to hurt people.”

When extended family members reported the alleged abuse to the church, the pastor’s response was “‘I can’t tell a man what to do in his own house,’” Kiser recalled. The pastor did not provide a response after a reporter repeatedly requested comment via voicemail and text.

“As a woman, it was our job to follow, never to lead,” Kiser said. “It was our duty to submit to the leadership of our father and our pastor, then after we married — young, of course — we were to be subservient to our husband.”

‘A normal man’

Kiser got married at 18 to a man more than six years older than her in 2017. They dated for about nine months but weren’t allowed to be alone together, so she barely knew him, she said. Her first kiss was at the altar.

Kiser said she wanted to marry him, but a large part of that was her desire to move out of her parents’ home and start her adult life. Marriage was the only way forward.

Sarah Kiser got married at 18 to a man more than six years older than her in 2017. They dated for about nine months but weren’t allowed to be alone together, so she barely knew him, she said. Her first kiss was at the altar.

“It’s hard to say that you actually wanted to do anything when you’re brainwashed into something,” Kiser said of her decision to marry.

It wasn’t long before her husband started to criticize her for not cleaning or cooking enough, Kiser said. He yelled and screamed, she said. He told her she was unattractive and not skinny enough.

Kiser said she didn’t feel safe being emotionally vulnerable with him, so she lost her sex drive. But Kiser said her husband would “badger and badger and badger” her until she would finally give in and have sex with him.

“For me, it was coerced consent or marital coercion,” Kiser said. “Because we were taught that a woman's body doesn't belong to her and the man's body doesn't belong to him, and you're supposed to have sex with your spouse even if you don't want to.”

Kiser said her pastors always left out the part about the man’s body belonging to his wife, even though that’s in the Bible. They focused instead on how women belong to men, Kiser said. She noted she had to ask for her pastor’s permission to go on birth control.

Sarah Kiser is pictured with her dog, Goose, in her home in Bristol, Va., Aug. 16, 2024. Goose is not the dog that her ex-husband allegedly abused.

“A lot of the abuse and the trauma for me really stemmed from never feeling like anything belonged to me,” Kiser said. “Nothing of mine ever belonged to me. Like, my body didn’t belong to me. My sexuality didn’t belong to me. Who I was as a person — my personality didn’t belong to me.”

A few times, Kiser said, the abuse in her marriage escalated to physical violence. Her husband would push her or throw things, she said. In one instance, she said he grabbed her by the throat and slammed her into the couch. Kiser said her husband would also kick their dog and “jerk him around” by the neck.

Lee Enterprises investigative team left voicemails and text messages for Kiser’s now ex-husband seeking comment on the alleged domestic violence, but he did not respond. Someone, possibly her ex, answered a phone call from a reporter in August but would not identify themselves and hung up after Kiser’s name was mentioned.

Sarah Kiser got married at 18 to a man more than six years older than her in 2017. They dated for about nine months but weren’t allowed to be alone together, so she barely knew him, she said. Her first kiss was at the altar.

Kiser eventually found the courage to tell someone about how her husband was treating her.

“‘He gets mad and yells at me, like screams at me, and throws things, and is just generally terrifying,’” she remembers confiding in her assistant pastor in Arkansas. “‘He’s even put his hands on me at a couple of points.’

“‘That’s a normal man,’” she said the pastor told her.

That assistant pastor also did not respond to voicemails and text messages requesting comment.

Kiser slowly started detaching herself from The Message. Then the pandemic started in 2020, and she and her husband moved to Wisconsin.

They found a Message church in the Wausau area but decided not to attend. She drank alcohol and wore press-on nails. When she told her Message parents she had started wearing pants, they said they didn’t want to see or talk with her anymore. She said they essentially “disowned” her.

Sarah Kiser is pictured in her home in Bristol, Va., Aug. 16, 2024. Kiser said her former faith, "The Message," taught her that women were supposed to be meek, quiet and submissive to their husbands.

Healing process

Kiser left her marriage and The Message in late 2020 when she was 22. After she left, she would have nightmares about sitting in church — imagery that’s not scary on its face but left her with a “feeling of intense fear.” She said she was diagnosed with complex post-traumatic stress disorder from her time in the sect.

“The healing process, it’s still going on,” Kiser said.

Kiser now lives in Bristol, Virginia. She said her life is different, but “so much better.” Kiser is in a polyamorous relationship with a partner who supports her and has built other friendships outside the church.

Sarah Kiser is pictured in her home in Bristol, Va., Aug. 16, 2024. Kiser said she is working on healing after enduring an abusive childhood and marriage in "The Message."

“I have surrounded myself with people who encourage me to express myself,” Kiser said. “People who see my fierceness and curiosity as a blessing instead of a curse. People who love me for who I am already and don’t try to force me to fit inside a box of their own design.”

She is taking aerial arts classes and has done some modeling. Kiser recently accepted a volunteer position as an assistant artistic director for a magazine starting up in New York. She works primarily as a pet sitter and house sitter, a flexible job that lets her focus on launching an accessory business to sell her hand-beaded purses.

Kiser said she finds joy in changing up her clothing and hairstyles.

In November, her hair sat at her shoulders in a short auburn bob. In August, her now sandy, strawberry-blonde hair had grown just past her shoulders.

Kiser said she has gone to therapy and become secure with who she is as a person — a confidence she never had in The Message.

“I want there to be more conversation about The Message. And I want it to be more mainstream (that) this is a problem. This is all over the U.S. and the world, really,” Kiser said. “I want my story to help people because what’s the point of going through something if you can’t use that to help somebody else or to make someone else feel less alone?”

Sarah Kiser at an event while she was a part of The Message.

A photo of Sarah Kiser from when she was a part of The Message.