Editor's note: This story contains a description of child abuse.

Naomi Wright grew up in what she described as a polygamous cult near Buffalo, New York. Her father was the leader.

Wright’s father amassed about 200 to 300 followers in western New York, central Ohio and Arkansas from the early ‘80s to 2007, she said. He would travel to the three areas to preach in people’s homes — and visit his multiple families.

Naomi Wright grew up with a father who practiced and preached polygamy. She has grown and healed from her traumatic upbringing and now runs a nonprofit called Be Emboldened that helps support people who have experienced religious abuse. Wright is pictured here in Waco, Texas, in April 2024.

“My specific sect got a little funkier than some of the other (Message) sects have gotten,” Wright said.

The religious group considered themselves followers of “The Message,” an offshoot of Pentecostalism started by 1950s-era faith healer William Branham. Believers consider Branham their prophet. Today, The Message movement has millions of followers across the globe, according to a rough estimate from Message organization Voice of God Recordings.

Most in the sect do not practice polygamy, experts say, but a few leaders within the movement have used some of Branham’s sermons to justify the practice. Wright said that created a community where young women were “preyed upon.”

Branham mentioned polygamy a handful of times in his more than 1,200 recorded sermons. He said he was against the practice but also spoke positively about it.

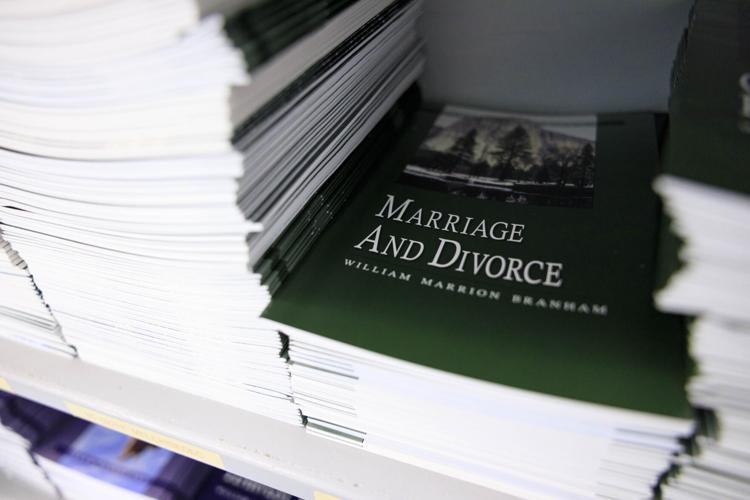

Booklets containing one of William Branham’s most controversial sermons, Marriage and Divorce, are seen at Voice of God Recordings’ production facility Jan. 15, 2024, in Jeffersonville, Ind. In the sermon, Branham preaches that a man can remarry many times as long as his new wife is a virgin, but women can never remarry. Branham, a ‘50s-era healing revivalist who was believed to be a prophet, died in 1965 but has millions of followers to this day.

In a controversial sermon called “Marriage and Divorce,” Branham preached that women can never remarry, but men can divorce and remarry as long as their new wife is a virgin. Some ministers have taken that doctrine to lay the theological foundation for polygamy: If Message men can remarry virgins as many times as they want, why not at the same time?

"Here's the prophet's word: He can remarry and remarry and remarry and remarry!” Virginia minister Elwood Gallimore preached to his congregation in 1993, according to the Washington Post. “He can! He can! He can! He can! He can! But she can't!"

Gallimore, who claimed to follow Branham’s teachings, gained national notoriety in 1993 for having two wives. Gallimore stayed married to his wife of 26 years while simultaneously “marrying” a 16-year-old girl, the Roanoke Times reported. To avoid breaking the law, Gallimore initially did not legally marry the girl, but he said they were married “in the eyes of God.”

Gallimore would jump and yell in support of polygamy as he preached. He used Branham’s sermon to defend the practice. But Branham’s two sons have always maintained that interpretation is the opposite of their father’s intent.

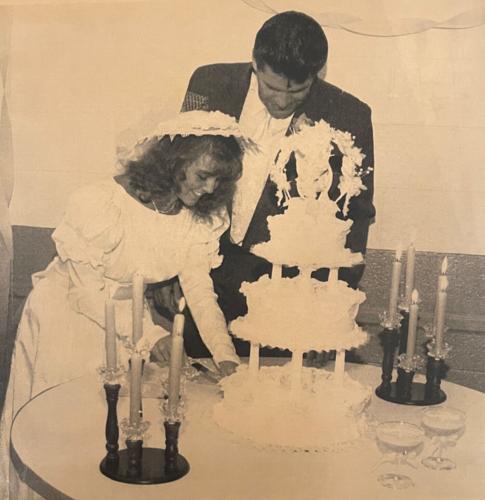

In this 1994 Martinsville Bulletin file photo, Sabrina Simpkins and Elwood Gallimore cut their wedding cake. Gallimore stayed married to his wife of 26 years while simultaneously “marrying” Simpkins when she was 16.

"Two living wives? At the same time?" Billy Paul Branham, who died last year, asked a Roanoke Times reporter in 1993. "That's what we call polygamy. We absolutely do not believe in that."

Voice of God Recordings, the nonprofit that Branham’s son Joseph Branham runs to continue his father’s ministry, remains against polygamy today. Nonprofit spokesperson Jeremy Evans said Branham “never stood for polygamy at all.”

Gallimore’s first wife, Janice, divorced him in 1994, and Gallimore legally married the teenager, Sabrina Simpkins, the Roanoke Times reported. Although no longer legally married, Janice still listed Gallimore as her husband when she died in 2007, according to her obituary.

Gallimore also took a third wife at some point. When he died at 73 in 2022, his obituary listed both Sabrina Hope and Sarah Ruth as his wives.

In this 1994 Martinsville Bulletin file photo, the Rev. Buddy Crotts of Axton officiates as the Rev. Elwood Gallimore puts the ring on Sabrina Simpkins's finger. Gallimore stayed married to his wife of 26 years while simultaneously “marrying” Simpkins when she was 16.

‘Awful environment’

Wright’s father had four and sometimes five wives at one time, Wright said. He had children with some of the wives, and others were young women, some 18 or 19, who only stayed married to him for a short time. Wright’s mother was closest in age to their father and was considered the “primary wife,” Wright said.

Wright shared her story on the condition of keeping her father anonymous. She said sharing his name could hurt his living family members who are still active in the sect.

Rev. William Branham

Her father’s support of polygamy started with Branham casting the practice in a positive light, Wright said. In one sermon, Branham says he doesn’t believe in polygamy, but “the nation in (sic) a whole would be better off if it practiced polygamy.” Wright would disagree.

“It created a really awful environment for the young men and the young women growing up in that culture. Because the young women, … they were being preyed upon. They were being groomed,” Wright said. “I remember someone trying to stake claim on me when I was only 8 or 9 years old.”

Her father didn’t let that happen. But some older men would claim 16- and 17-year-old girls as their future wives, Wright said. That took away potential wives for the young men.

The young women weren’t forced into the polygamous unions with her father, Wright said, but she thinks some were manipulated. Their parents believed it would be advantageous for their daughters to marry their faith leader. The group considered Wright’s father to be the prophet or “voice box of God” who came after Branham, she said.

“I know for a fact young women did not want to be 17, 18 years old and marrying a man in his 50s. They were horrified by that idea,” Wright said. “But the parents had a different view.”

Wright’s father’s polygamous lifestyle created an unstable home environment for her and her brother. They lived in New York with their mother while their father was gone for weeks at a time to visit his children and wives in Ohio and Arkansas. Wright was supposed to consider those half-siblings her full siblings, but to the outside world, she had to pretend they were her cousins when they came to visit.

“Because polygamy is illegal in the states in which he was practicing them, we were coached that we couldn’t tell anyone,” Wright said. “We had to be secretive about pretty much everything.”

Naomi Wright grew up with a father who practiced and preached polygamy. She has grown and healed from her traumatic upbringing and now runs a nonprofit called Be Emboldened that helps support people who have experienced religious abuse. Wright is pictured here in Waco, Texas, in April 2024.

Although destabilizing, her father’s absence was also “a Godsend,” Wright said. When home, their father sporadically physically abused her and her brother, knocking their heads together or throwing them into walls, she said. She said her father once beat her for giving herself bangs when she was 6. Branham said it’s immoral for women to cut their hair.

Wright believes Branham’s teachings contributed to her father’s abusive and misogynistic practices. Branham taught that women were “hogs,” “jezebels” and “just worthless,” Wright said.

“My dad growing up the way he did maybe he would have been abusive anyway,” Wright said. “But to have someone who is sort of your mentor and you’re following in their footsteps who talks about women in the way that William Branham did, there’s no way that’s not going to make it worse or at least is going to further entrench that way of thinking about people.”

When Wright’s father died in 2007, more men in her religious group were embracing polygamous lifestyles, she said. Wright left the group several years later. She’s not sure if they still practice polygamy.

In this 1993 Bulletin file photo, Sabrina Simpkins, center, and Janice Gallimore — Elwood Gallimore's two "wives" — talk to the media during the lunch break from court.

Polygamy in Africa

Although rare overall, polygamous interpretations of Branham’s message have spread across the world. The practice is more common in African Message churches, said John Collins, an ex-Message believer who now runs the William Branham Historical Research website. Collins has written several books on Branham's message including, "Weaponized Religion: From Latter Rain to Colonia Dignidad."

Martin Maene, 19, a former believer who grew up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, said he was aware of two or three small Message congregations that practiced polygamy in that area. But he noted that most Message churches condemn the practice.

Uganda pastor Patrick Kimera said Branham inspired him to practice polygamy, according to a 2013 article in the Daily Monitor, a Ugandan newspaper. Kimera had four wives.

“His message on marriage and divorce was the first time a preacher helped me understand why I still loved one wife and wanted another one,” Kimera told the newspaper. He said he modeled his church after Branham’s ministry.

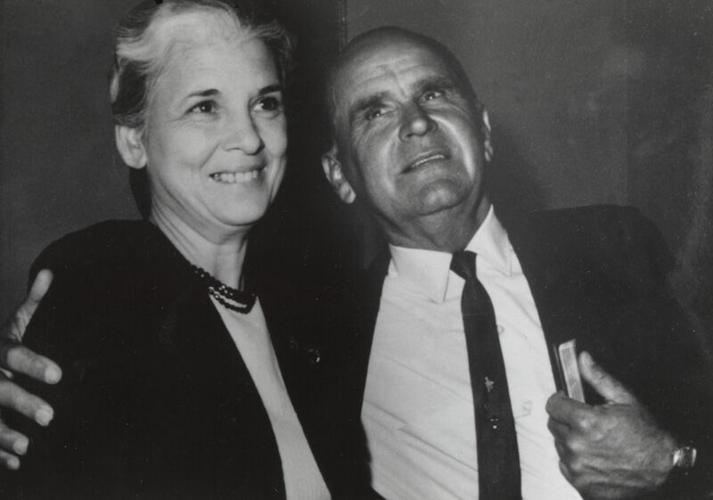

Rev. William Branham and his wife Meda Branham. Branham married Meda after his first wife, Amelia, died in 1937. He did not practice or support polygamy.

Kimera started practicing polygamy in 2001, the Daily Monitor reported. He preached Branham’s “Marriage and Divorce” sermon to his congregation at the End Times Gospel Church and told them he planned to marry a second wife — a message that Kimera said elicited cheers. But when he introduced that woman, many members left the church and sued him to try to kick him off the church property.

Kimera told the newspaper he had been in and out of court for more than a decade over the dispute. He still had a small group of loyal followers in 2013.

About 2,000 miles south of Uganda and decades before, another African minister with ties to The Message took multiple wives.

In Zimbabwe around 1980, a young man named Robert Gumbura joined a Message church, Zimbabwean researchers Fortune Sibanda and Bernard Pindukai Humbe wrote in a 2020 chapter of the book “#MeToo Issues in Religious-Based Institutions and Organization.” Over time, Gumbara broke away to form his own church. And he took up polygamy.

Gumbura was able to open several churches and gain thousands of followers, all while marrying and having sex with many women in the congregation, Sibanda and Pindukai Humbe reported. But it fell apart beginning in 2014 when he was arrested and accused of rape, charges that eventually landed him a 40-year prison sentence.

As part of that court process, the judge and other personnel visited one of Gumbura’s lavish properties. On the wall: A painting with Jesus at the center, Gumbura on one side, and Branham on the other.

Recovery

Message churches in the U.S. are widely against polygamy today. Wright said that when her father started endorsing the practice, he was excommunicated from a slew of Message churches in the Northeast.

Naomi Wright grew up with a father who practiced and preached polygamy. She has grown and healed from her traumatic upbringing and now runs a nonprofit called Be Emboldened that helps support people who have experienced religious abuse. Wright is pictured here in Waco, Texas, in April 2024.

“We see things in the Bible the way we want to see them because it makes a desire that we have OK, instead of actually correcting the desire and reigning that in,” Wright said. “I believe that is what happened here.”

Wright, 39, now runs a nonprofit called "Be Emboldened" that helps support and mentor people who have experienced religious abuse, including some who have left The Message. Licensed mental health professionals who have been through religious trauma themselves help survivors rebuild and recover. The nonprofit offers courses that cover topics such as how to grapple with grief, rebuild one’s life, manage emotional triggers, develop boundaries and learn to trust again.

“There is something precious about having purpose coming out of such tragedy,” Wright said. “I want to offer the encouragement that where people are right now, it doesn’t have to be permanent. Our lives can look so different. There’s so much hope, and there’s so much possibility for change.”

In this 1994 Bulletin file photo, wedding guests pelt Sabrina and Elwood Gallimore with birdseed as they leave the reception.

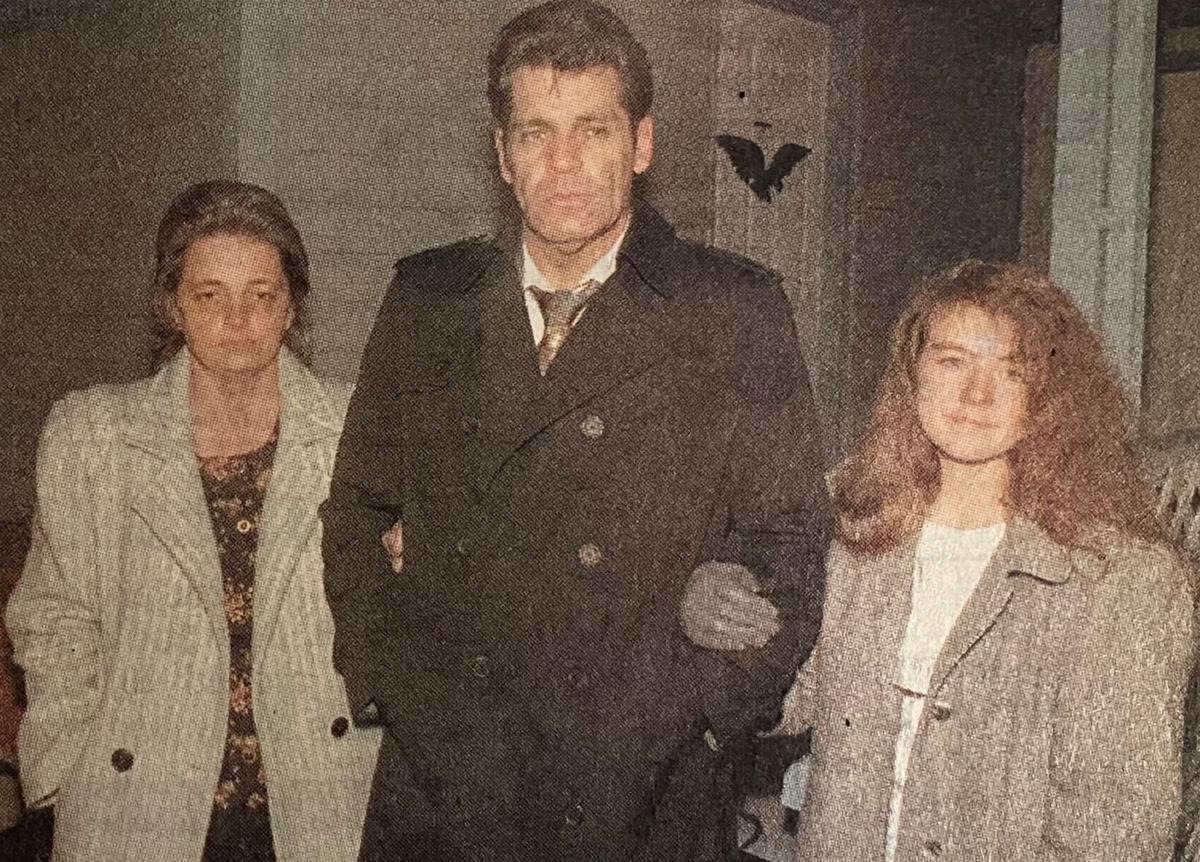

In this 1993 photo, Elwood Gallimore poses with Sabrina Simpkins, 16, and Janice Gallimore, 42, whom he called his wives.

In this 1993 Bulletin file photo, Gallimore and wife Janice (concealed behind coat) leave services.