To earn his diploma from Sunnyside High School, Edgar Casas, 19, fought for his life.

As a high school freshman, he was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

At the time, he was living in Phoenix with his grandmother and had never been seriously sick before. His schooling ceased when treatments began at Cardon Children’s Center in Mesa.

There, he met Monica Molina and her daughter Marissa Molina, who was at the hospital to receive treatment for bone cancer.

“He took care of himself a lot during his treatment and was often by himself,” Monica says. “But he was always smiling and always stayed positive. He didn’t feel sorry for himself or anything like that and didn’t have the support that most of the kids had there.”

Monica remembers Casas taking taxis to and from treatment and making trips to the grocery store to make his own meals. Monica, her daughter and many of the nurses rallied around the teen.

Casas didn’t give up on school. Instead, he earned 12 credits through homebound schooling via Bostrom High School in Phoenix.

But treatment didn’t go well. He relapsed twice. The cancer came back despite chemotherapy and radiation.

With his immune system weakened from chemo, Casas says he developed a brain infection that could have cost him an eye. After almost three years of treatment, he was done.

He decided to go back to Mexico, where he had lived as a child after being born in California. His mother still lives there, and Casas believed his quality of life would be better with his family.

“It was a scary decision ... but it was worth the risk,” Casas says.

His doctors pleaded with him to stay, telling him he would not live long if he stopped treatment.

“I had so much hope in me that I knew they were wrong,” he says.

Casas spent about six months with his family in Mexicali, taking no prescribed medications and undergoing no treatment.

“I felt like God wanted more for me than what they had given me,” he says. “I felt like I deserved more.”

And so he needed to finish school.

He reconnected with the Molinas, who promised him they would help enroll him if he moved to Tucson. Monica works as an administrative assistant for the Sunnyside Unified School District office.

Casas moved to Tucson in spring of 2014 started school in August and got involved in Youth On Their Own, a nonprofit that helps unaccompanied teens graduate.

“Nowadays, if you don’t have a high school diploma, you don’t get a good job,” Casas says. “The diploma is the first step towards your career.”

But another setback came in the form of pneumonia and a trip to Banner-University Medical Center toward the end of 2014.

Doctors noticed Casas had a low count of platelets, which help blood clot. A follow-up visit in January revealed Casas had MDS, or myelodysplastic syndromes, meaning his bone marrow did not make enough healthy blood cells.

“The transplant doctor said it was critical and that he needed to get a (stem cell) transplant right away,” Monica Molina says. The hospital admitted Casas in March, and he began chemotherapy to prepare his body for the transplant.

Again, his education went on hold.

He spent 72 days in the hospital but was able to resume homebound schooling until he could return to Sunnyside in August to finish his remaining credits in a modified setting.

Medically, he is in maintenance for the transplant, which means he visits the hospital every few weeks for checkups and to refill his medication.

There are no signs of the leukemia, though his weakened immune system still has him in and out of the hospital for various illnesses.

“There are just so many setbacks because the transplant put stress on his body,” says Marissa Molina, 19. “The doctors still say Edgar is not himself.”

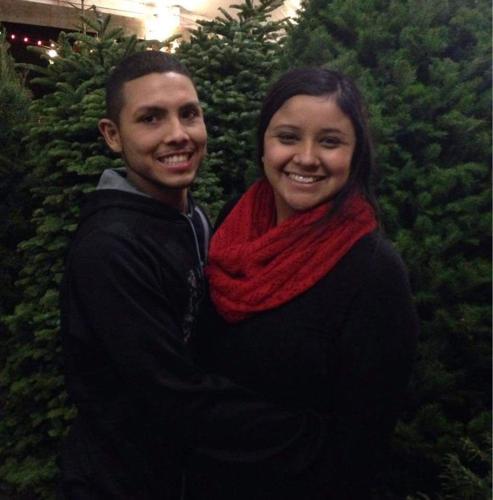

It takes time to regain strength, adds the younger Molina, who has been in remission for about five years. She and Casas are dating.

Casas has hope for his future. Earlier in December, he completed his high school coursework at Sunnyside High School. He will walk in the graduation ceremony in May.

“He believes more in his God than the doctors,” Monica says. “He believed he had more to do here.”

Casas doesn’t know exactly what he wants to do next, but he is drawn to the medical field. Perhaps he will become a nurse or EMT, he says. He wants his own experiences to make cancer treatment less scary for other kids by explaining exactly what they can expect.

“The nurses don’t prepare you,” Casas says. “They tell you everything by the books, but they can’t tell you personal experience or what could happen just because they can’t release anyone’s information. ... But me, myself, I don’t care. I’ll tell them my story.”