Researchers at the University of Arizona hope a $2.27 million federal grant will help them build a genetic profile of people who get severely ill from valley fever.

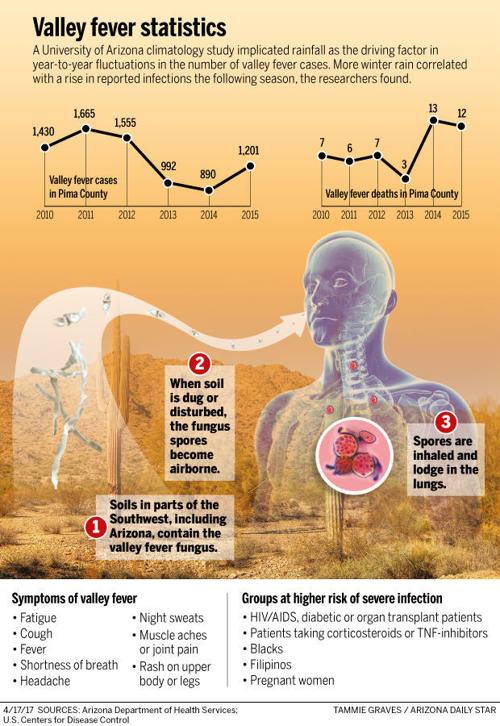

Some genetic factors are already known to put people at higher risk for the potentially deadly respiratory disease — gender, blood type and ethnicity. Other risk factors include a compromised immune system and pregnancy.

The biggest risk factor is geography: More than 65 percent of all valley fever cases in the U.S. occur in Arizona, and 30 percent occur in California. Most other cases occur in Nevada, Utah and New Mexico. Nearly 6,200 cases of valley fever were recorded in Arizona last year, including 54 deaths, preliminary state health data show.

But UA researchers want to focus on the specific genetics of those who get very sick with the disease and are neither pregnant nor immunocompromised, said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the UA’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence.

“It’s a major commitment to understanding why some people get really bad (valley fever) disease,” Galgiani said. “I can’t remember funding for that from the NIH in a long time.”

200 patients

The UA researchers are hoping to include about 200 patients in their study, which is called “Immuno-Genetic Basis for Human Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis.” Coccidioidomycosis is the scientific name for valley fever.

One result could be the ability to tell a patient with a particular DNA sequence that if they were to get valley fever, it would disseminate. When valley fever disseminates, that means it goes to the bloodstream, moving from the lungs to the skin, bones and joints, the spinal cord, and brain.

Or if that same patient were to get pneumonia and get a valley fever diagnosis, then medical providers may have to be more aggressive about treating it.

The four-year grant is from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and technically amounts to $2.7 million, Galgiani noted, as the NIH will do part of the work and has been awarded $500,000 for its role.

NIH researcher Dr. Steven Holland will be a co-investigator along with the UA team, which includes Galgiani and Dr. Yves Lussier, who is the associate vice president and director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics and Biostatistics at UA Health Sciences as well as associate director of the UA’s BIO5 Institute.

Severe illness

Current research shows one of every three people who inhales a coccidioides fungal spore gets sick enough to go to a doctor. In one of every 200 people who get sick, the valley fever disease disseminates.

Studies have already found higher rates of disseminated valley fever in men than in women, and in African Americans and Filipinos versus other ethnic groups. Also, certain blood groups — B and AB — have been identified in studies as more likely to get the disseminated version of the disease.

But Galgiani said the UA researchers are looking for more specifics.

“We want to know the mechanisms. ...We have associations but we don’t actually know what differences drive those associations,” he said. “The associations are not all-or-none. African Americans have a higher rate of severe disease, but most African Americans still don’t get severe disease.”

Galgiani is hoping researchers might also understand whether any genetic factors might prevent a vaccine from working on people with disseminated valley fever.

“An underlying question about vaccines is would they actually help the people who would benefit the most?,” Galgiani said. “We’re going to address that. It could be the vaccine works only for people who don’t get disseminated cocci.”

In a separate project, UA researchers are working with a veterinary startup on developing a live vaccine against valley fever made from a mutant fungal spore. The research team, which has applied for a separate NIH grant for the vaccine development, is hopeful the vaccine will work on both humans and dogs.

Death from valley fever

Sue Medinger, who lost her husband to disseminated valley fever Aug. 24, says anything that will focus more on valley fever awareness and prevention is a step in the right direction.

The Medingers divided their time between Tucson and San Antonio, and Sue is certain her husband contracted valley fever in Tucson, where the couple owned a townhome. Her husband, Joseph David Medinger, was an avid UA Wildcats fan. The couple got engaged in front of Old Main in 1966 and were married here in 1968.

Yet no one in the family, nor the doctors they saw in Texas, suspected valley fever until it was too late, Sue said. Her husband, who also had diabetes, was admitted to the emergency room with what appeared to be severe pneumonia just days before he died at the age of 71. Initially, doctors thought he might have tuberculosis, she said.

“It is hard to know he might have been saved if we’d had the right information,” Sue said. “There’s just not enough awareness.”

Galgiani said awareness and the purpose of the latest grant are not mutually exclusive.

“Knowledge is valuable. If we know exactly, we might be able to replace what’s missing, or suppress what’s too much therapeutically and prevent you from disseminating,” he said. “If you know it’s broken, you can more likely fix it.”

It may turn out that people with disseminated valley fever have a slow immune response to the disease, Galgiani said.

“The reason that is so important is that means that a vaccine actually would prevent it. If you vaccinate them and bring up that immunity way before they see the infection, they are now immune.

“So this work has real practical value. We’re trying to help patients with this. That’s why the NIH funded it.”