For the 51st time in the last month, a parent wanted to know the whereabouts of her child. And for the 51st time, the authorities in federal court in Tucson did not tell her.

Flor Berillos de Lopez pleaded guilty to crossing the border illegally June 10 near Lukeville with her 15-year-old daughter, who was taken from her by the Border Patrol hours before Berillos’ June 12 hearing at U.S. District Court in Tucson.

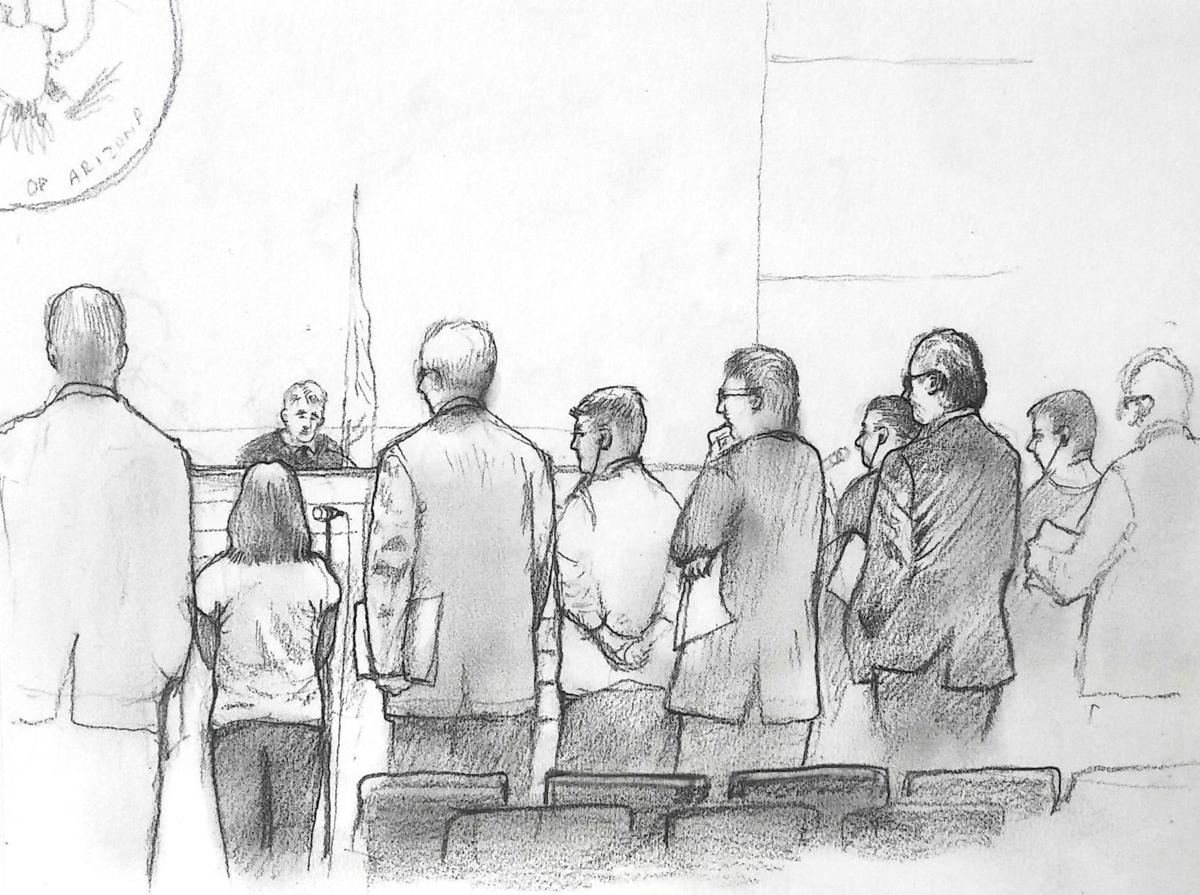

“They were separated this morning and she does not know where her child is,” defense lawyer Joe Machado told Magistrate Judge Bernardo P. Velasco during an Operation Streamline hearing, a fast-track prosecution program for illegal border crossers.

The exchange came a week after Magistrate Judge Bruce G. MacDonald told federal prosecutor Christopher Lewis to call the agency responsible for the children and report back with a way for parents to know where their children are.

On June 6, U.S. Attorney’s Office spokesman Cosme Lopez said prosecutors in Tucson were working with law enforcement and the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which places children split from their parents in foster care or with family members, to develop a “mechanism” to keep parents informed about their children.

A week later, Lopez said he was “unsure” what was happening with the mechanism.

Prosecutors are still working with federal law enforcement and the courts to develop the mechanism, Lopez said. They also are consulting with other federal judicial districts on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Lopez declined to discuss the obstacles to putting a system in place. The Office of Refugee Resettlement did not respond to a request for information, nor did the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector.

Meanwhile, 51 parents from Central American countries, most of whom are Guatemalans who turned themselves in to Border Patrol agents near Lukeville, have asked magistrate judges in Tucson for the whereabouts of 55 children, according to an ongoing review of court records by the Arizona Daily Star.

Along the entire U.S.-Mexico border, the Border Patrol held 1,995 minors traveling with 1,940 adults between April 19 and May 31 while the adults were criminally prosecuted, a Department of Homeland Security spokesman said Friday.

The separations came after Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced a zero-tolerance policy for prosecuting illegal border crossers. As a result of that policy, children are separated from parents who are criminally prosecuted for crossing the border illegally.

In mid-May, when parents started asking magistrate judges in Tucson where their children were, often amid tears, the judges put their requests on the record. Then the judges started recommending families be reunited after parents are released from criminal custody. The judges often reiterate that their recommendations are not orders.

MacDonald’s request to prosecutors marked a next step, but federal prosecutors, who are referred to as “the government” in court, have so far pointed at other federal agencies when asked by judges for information on children’s whereabouts.

“If there was a will, there’d be a way,” defense lawyer Machado said in an interview. “I just don’t think the proper effort is being expended to make a bad situation bearable.”

Machado said the authorities’ actions in Berillos’ case “didn’t make sense.”

Berillos and her daughter were taken into custody two days before their hearing, but they weren’t separated until the morning of the hearing.

As is the case with most parents prosecuted through Streamline, Berillos was scheduled to be sentenced to time served, released and deported.

“You would think they would know that and keep them together,” Machado said.

Berillos planned to file an asylum claim based on her fear of returning to El Salvador, “But she was so distraught about her daughter she didn’t even care about that anymore,” he said. “She wanted her daughter.”

Some of the children separated from their parents are placed by the Office of Refugee Resettlement at a government-funded shelter in Tucson run by Southwest Key.

When children arrive at the shelter, “They have no idea where their parents are,” nor do the case managers, said Antar Davidson, who worked at Southwest Key’s shelter in Tucson from February until he resigned June 12.

He was told to tell a Brazilian child it would take a week to locate his parents and another week to arrange a conversation. After arrangements are made, most children get two phone calls each week to talk to their parents, he said.

Davidson is a field director for state Rep. Pamela Powers Hannley, a Tucson Democrat. She recently co-sponsored a bill to increase transparency at private prisons funded by tax dollars. Davidson said he opposes private prisons and “detainment for money.”

He decided to talk about what he saw at the shelter because he “felt a personal responsibility to kind of share their struggle and help ease their pain.”

Before the zero-tolerance policy, the children placed at the shelter had crossed the border on their own, rather than being separated from their parents, Davidson said. They expected to spend months without family members, and many already had set up sponsors in the United States.

But the zero-tolerance policy started filling the shelter with children who were “traumatized from being forcibly removed” from their parents, he said.

While answers for parents are unavailable in court, local nonprofits try to fill the void.

Among their efforts is providing a petition for an asylum hearing to Streamline defendants and sending emails to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said Peter Hirschman, a member of the End Streamline Coalition and the asylum team leader for Keep Tucson Together.

When the petition is passed along to the appropriate agency, “It seems to work pretty well,” he said.

In the case of a Guatemalan woman who was prosecuted in mid-May, her lawyer put the names of the children on an ICE form and arranged for a hearing to explain her fear of returning to Guatemala. The mother was able to speak with her children and then get in touch with her sister, who is trying to have the kids placed with her in North Carolina, Hirschman said.

At the detention center in Eloy, where ICE records show at least 12 parents prosecuted in Tucson were detained while awaiting deportation after being released from criminal custody, posters near the phone used by detainees explain how to contact the Office of Refugee Resettlement, Hirschman said.

In some cases, the Guatemalan consulate also is arranging for parents to be reunited with children at airports before flying back to Guatemala, he said. But if those arrangements don’t work, children may spend months separated from their parents.