First of four stories

|

Oscar’s phone battery was failing as he tried to stay on the line with the 911 dispatcher.

He had crossed the Arizona-Mexico border southwest of Tucson a few days earlier, but he was running out of food and couldn't keep walking through the Baboquivari Mountains. His call to 911 came during a record heat wave that turned September 2020 into one of the deadliest months for migrants ever recorded in Southern Arizona.

"I'm lost and alone," Oscar said through a shaky connection with a dispatcher at the Pima County Sheriff's Department, which recorded the call. "I've been lost for two days and I have almost nothing to eat here so I called this number."

The battery was running out. "It's down to 5%," he said.

The dispatcher connected Oscar's call to the Border Patrol, but the call dropped even though multiple carriers provided coverage in the location he called from.

"Hopefully, he's able to call back," the Border Patrol agent said.

Oscar called again but the call dropped. He called again, and this time the coordinates showed him to be about a mile away from the site of his original call.

"I only have 3% of my battery left," he said. An agent told him to send a text message through the WhatsApp messaging service instead of using his phone battery on a call.

Oscar called back again, pleading, "please don't leave me here." The Border Patrol sent an aircraft to look for him, but Oscar said it was flying on the wrong side of the mountain.

"I don't want to be here anymore," Oscar said. "I don't have anything left. I didn't think things were going to be so hard here."

His battery was at 2%.

"My wife is about to give birth and I prefer to just go back there. This is killing me," Oscar said. He started to sob.

A Border Patrol agent took over the call and the 911 audio recording stopped.

Oscar's fate isn't known. The Sheriff's Department later said the Border Patrol found him, but the Border Patrol could not find any record of what happened to him.

He was one of thousands of migrants who cross the border in Southern Arizona every year. Each year, many of them are overwhelmed by the harsh deserts and mountains, leading to distress calls to 911 dispatchers, family members and local humanitarian groups.

Some find help. Others do not.

Over the past two decades, the remains of more than 3,900 migrants were found in Southern Arizona, according to the Pima County Medical Examiner's Office, the Tucson-based aid group Humane Borders, and the Yuma County Sheriff's Office. An unknown number of others also died while crossing the border, but their remains were never found.

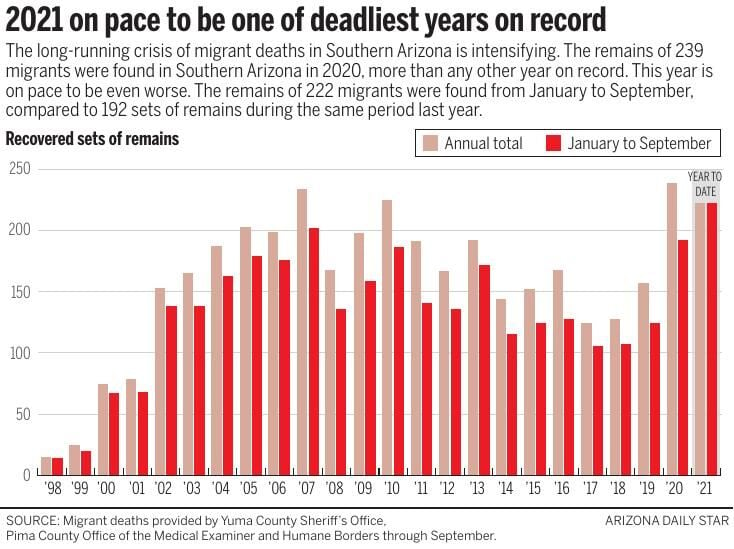

The long-running humanitarian disaster is intensifying. Within weeks of Oscar’s calls for help, the remains of 36 migrants were found, making September 2020 the deadliest month since 2013. By the end of the year, the remains of 239 migrants had been found, more than any other year since large-scale deaths in the desert of Southern Arizona began in 2000.

Until this summer.

After the remains of 52 migrants were found in June, more than any month since 2010, the death toll so far in 2021 is on pace to surpass last year. The remains of 222 migrants were found in Southern Arizona from January through September, compared to 192 during the same period last year and 124 during that period in 2019.

"2020 does not look like a one-year blip," said Dr. Greg Hess, Pima County's medical examiner, who oversees the vast majority of remains recovered in Southern Arizona. "We're super busy over these types of remains in 2021 and I imagine we're going to come close to the numbers we had last year."

The increase in migrant deaths is raising the stakes for President Joe Biden as he seeks to overhaul immigration policy. Hundreds of predictable and preventable deaths could continue for the foreseeable future without urgent and sustained action by federal authorities, but that action is nowhere on the horizon.

As has been the case for the past two decades, the thousands of migrant deaths flit around the periphery of the immigration debate but rarely become the center of attention. Biden has proposed a wide array of new immigration and border policies, but they are not aimed at helping migrants in the desert.

To understand the crisis, the Arizona Daily Star analyzed medical examiner data in multiple Southern Arizona counties and built a statistical model of migrant deaths.

We listened to audio recordings of 911 calls from migrants and reviewed incident reports from law enforcement agencies. We also tracked how lawmakers discussed those deaths; and interviewed migrants, scholars and officials. We visited sites where migrants died, and walked through the desert and mountains with Border Patrol agents and humanitarian volunteers.

The Star found the Border Patrol, humanitarian groups and local law enforcement work hard to rescue migrants. But no one is in charge of those efforts or held accountable, despite the need to coordinate across 20 jurisdictions and work with humanitarian groups and the families who lost loved ones in the desert.

The Star also found the scope of the crisis remains unclear, even after two decades of migrants dying in large numbers in the desert. The Pima County Medical Examiner's Office is the only agency involved that does not take a lethargic approach to record-keeping. As a result, migrant deaths tend to be treated as isolated incidents, rather than as part of a large phenomenon.

Perhaps most importantly, the lack of clear rules for providing humanitarian aid blocks the intellectual power and volunteer energy the Tucson community unleashes when an extraordinary migration event occurs, from the Sanctuary Movement in the 1980s, when Tucson churches and activists helped refugees fleeing violent conflict in Central American countries, to the volunteers and donations that keep the Casa Alitas shelter for asylum-seeking families in Tucson running today.

All this is unfolding as the U.S. Senate considers the nomination of Chris Magnus, current chief of the Tucson Police Department, to be the next commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, which oversees the Border Patrol. A key committee narrowly approved moving forward with his nomination process on Nov. 3.

The Star's investigation found that:

Exposure to the elements, particularly heat, is the most common cause of death, leading to 1,390 deaths and likely many of the 1,866 sets of skeletal remains where cause of death was undetermined.

The journey has grown more dangerous over the years, due in part to walls and barriers funneling migrants into remote areas. Today, remains are found an average of 17 miles from towns.

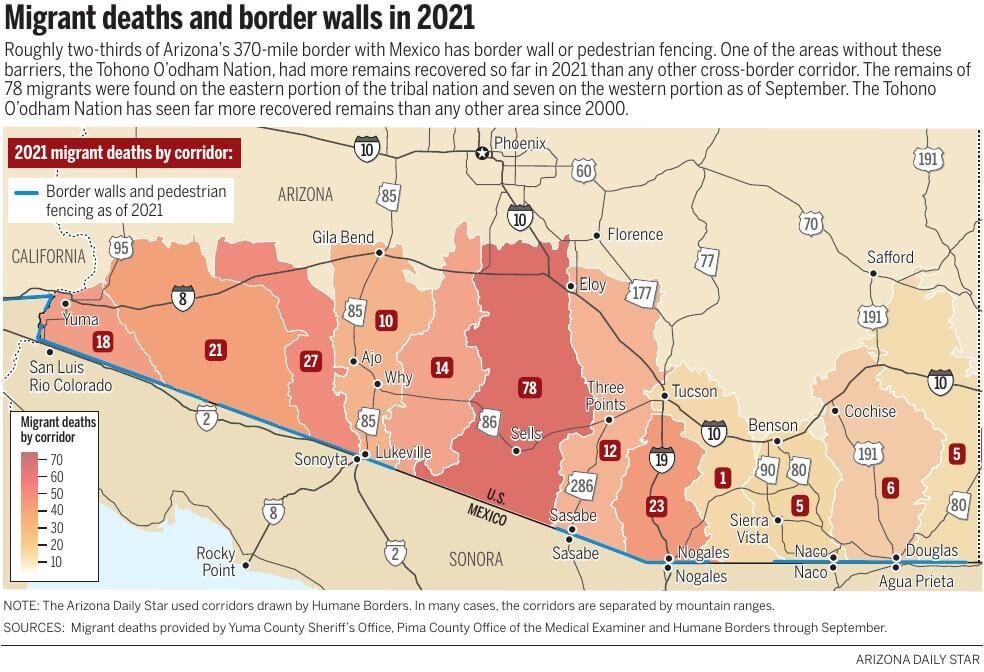

Southern Arizona's desert is as large as several states, but deaths are concentrated in specific areas. About half the deaths in 2021 occurred in 6% of that area.

Migrants often can't call for help. At least 514 migrants died in areas without cellphone coverage.

Migrants often die just hours before help arrives. More than 1,000 migrants died less than 24 hours before the discovery of their remains.

Opposing principles

The political decisions that shape the official response to migrant deaths have become wrapped up in the debate over border enforcement without being "elevated to the discussion it needs to have," said U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva, a Democrat who has represented districts along Arizona’s border with Mexico since 2003.

"Politically, if you show any empathy, any response short of enforcement, then for some reason you fall into the category of those that don't want to do anything about the border, and you fall into the open-border discussion," Grijalva said. "So politicians have backed away from it."

Without clear guidance from Congress, the public policy response to migrant deaths remains caught between opposing arguments.

On one hand, the argument is that if migrants didn't cross the border illegally and try to evade Border Patrol agents, they wouldn't risk dying in the desert.

"No one wants anybody to die," Border Patrol Agent Jesus Vasavilbaso said as he sat next to a trail in the Baboquivari Mountains where a migrant from Mexico died last year.

"If we had 100% apprehensions, nobody would die," Vasavilbaso said.

"Strong border security and interior enforcement is the best way to stop loss of life," U.S. Rep. Guy Reschenthaler, a Republican from Pennsylvania, said during a debate on the House floor in December 2020, over a bill that would direct federal officials to count migrant deaths.

"In reality, to prevent future deaths at the border, we need to make it absolutely clear that no one should embark on this dangerous journey because illegal entry is simply not an option," Reschenthaler said.

On the other hand, the argument is that border enforcement strategies put migrants’ lives in danger by leaving only one option, crossing through deadly terrain rather than through ports of entry, as they look for a better life in the United States or flee poverty, corruption and violence in their home countries.

In 2005, U.S. Rep. Jim Kolbe, a Republican who represented Southern Arizona from 1985-2007, described a "hard lesson" learned in Arizona after a vast increase in the number of Border Patrol agents and technology in previous years: "No matter how much we increase our enforcement, still the illegal migrants kept coming, at the same rate or faster than they had come in previous years."

"The border buildup did not stop the flow; it merely shifted it to more dangerous areas, where apprehensions are more difficult and death more likely," Kolbe said in remarks on the House floor, archived by the Library of Congress.

Over the last two decades the Border Patrol "monopolized the emergency response to a crisis of their own creation," the Tucson-based aid group No More Deaths wrote in a February report.

"Only abolishing Border Patrol policies and practices that cause people to become lost, missing, and injured in wilderness terrain in the first place will stop death on the southern border," said the No More Deaths report.

'For my family'

Damaris, a 25-year-old woman from Guatemala, had heard about the dangers of crossing the desert, but a family member was able to loan her the money this summer to make the journey. She decided to take advantage of the opportunity.

"You have to overcome," she said at a migrant shelter in Nogales, Sonora, in late July. "You make the decision to risk your own life and you say 'for my family.'"

The Border Patrol had picked up her group the day before, after they walked through the desert for more than a week. She didn't know where they crossed the border, saying "everything looks the same."

As she traveled to the United States, she met a 50-year-old woman from El Salvador who sobbed as she described her ordeal in the desert.

"We don't know who to trust," she said through tears.

Joel Mondragon, a 27-year-old man from the Mexican state of Jalisco, had been in Nogales for nearly two months. He and his family, including young daughters, did not plan to try to cross the border through the desert.

Joel Mondragon, who traveled from the Mexican state of Jalisco, said he and his family would not risk a surreptitious border crossing. From a shelter in Nogales, Sonora, he added: “They told me about asylum here and I think it’s better, more correct, to do things right.”

"I wouldn't risk it," he said.

"They told me about asylum here and I think it's better, more correct, to do things right," Mondragon said.

Damaris and Mondragon were among more than 100 migrants and asylum seekers seated at long tables inside the Kino Border Initiative shelter in Nogales, Sonora. Many of them erupted in loud applause as asylum seekers took turns with a microphone to call on Biden to let them make their claims at the port of entry a few miles away.

They spoke in front of a mural portraying a border version of Leonardo da Vinci's "The Last Supper," with Jesus surrounded by migrant parents and their children. The windows behind Jesus in the mural showed the wilderness and mountains of Southern Arizona stretching into the distance.

That wilderness covers the equivalent of Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island combined. It includes harsh desert, steep mountain ranges, and vast areas with few towns and roads.

Organ Pipe National Monument is one of a handful of areas where migrant deaths tend to cluster. At right is a formation migrants refer to as “Buddha Rock.”

Crossing the wilderness

From a car, the Altar Valley flies by on Arizona 286, which connects Three Points and Sasabe southwest of Tucson. On foot, the 45-minute drive turns into days of walking across rough terrain rutted with ravines.

Walking is even more treacherous on the trails that run along ridges in the nearby Baboquivari Mountains, which Customs and Border Protection officials in Arizona say have become one of the main thoroughfares for migrants crossing the border.

The area also has long been one of the deadliest for migrants, medical examiner numbers shows. The remains of nearly 1,400 migrants were found since 2000 in the corridor on the west side of the Baboquivari Mountains on the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation, including more than 140 since January 2020.

On the east side of the mountains, the remains of about 550 migrants were found in the Altar Valley since 2000, including at least 35 since January 2020.

The trek is made more difficult by the fact that many migrants already walked for days on the Mexico side of the border, as a couple from the Mexican state of Oaxaca did last December.

They sat glumly on a stone next to a dirt road in the mountains a few miles north of the border. They had been walking for four days and couldn't continue, they said. They tried to call for help, but they couldn't get cell reception and decided to wait for someone to come by.

This couple from the Mexican state of Oaxaca had already walked for days south of the U.S. border when they encountered Border Patrol Agent Jesus Vasavilbaso a few miles north of it. They said they couldn’t continue.

As Border Patrol Agent Jesus Vasavilbaso questioned them, they emptied crackers and vitamin water from their backpacks and showed him the street clothes they wore under camouflage pants and jackets. Minutes later, they got into the back of a Border Patrol truck. From there, they likely were expelled to Mexico, left to decide whether to give up or try to cross the border again.

Had the couple from Oaxaca continued their journey, they might have met the same fate as Jovita Garcia Ortiz, a woman from Hidalgo, Mexico, who died near the northern edge of the Baboquivari Mountains.

Garcia was traveling with a group of migrants, but she fell behind in early August 2020.

Her fate was unknown for more than a month. On Sept. 11, 2020, a Border Patrol Search, Trauma and Rescue (Borstar) agent called the Sheriff's Department to say they were tracking a group of migrants near the Border Patrol checkpoint on Arizona 86, not far from the northern edge of the Baboquivari Mountains. A Border Patrol dog led the agents to Garcia, who appeared to have died several weeks earlier.

The Pima County sheriff's deputy who went to the scene remembered an Aug. 15 report from No More Deaths volunteers, who relayed a call from Garcia's family. Another migrant in the group had called the family to let them know Garcia had fallen behind.

At the time, deputies believed Garcia's last known location was on the Tohono O'odham reservation. A deputy alerted the Tohono O'odham Nation Police Department and the Border Patrol, but it turned out that Garcia was not on the reservation. The phone she carried with her showed missed calls and text messages sent days earlier.

Like Garcia, about half the migrants whose remains were found in Southern Arizona were from Mexico. Another 12% were from Central American countries such as Guatemala. The medical examiner could not determine the nationalities of 37% of the found remains.

Remains are far more likely to belong to men, accounting for nearly 3,100 remains where gender could be determined, compared with about 500 belonging to women.

In terms of age, about 1,600 were between 18 and 39 years old and about 460 were in their 40s or 50s. About 100 were under 18 years old. The ages of about 1,500 could not be determined.

Shaky correlation

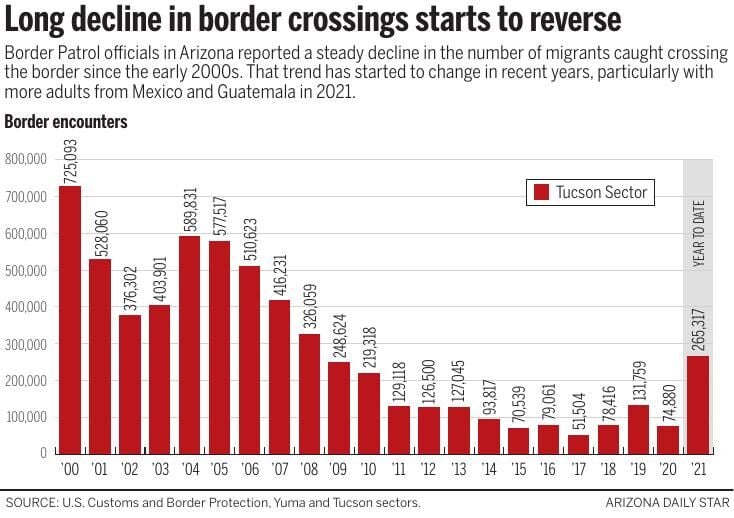

A sharp increase in border crossings since the winter when Biden took office dominated news coverage and political rhetoric about the border, which might make it tempting to point to the rise in crossings as the obvious explanation for more deaths in the desert.

But a rise in crossings doesn't fully explain a rise in deaths, the Star found by comparing Border Patrol statistics on encounters with migrants, which generally are used as an indicator of overall crossings, and medical examiners' data from Arizona's border counties.

Agents in Arizona reported more than three times as many encounters with migrants in 2021 than they did in 2020, but the number of remains found in those years stayed on the same record-breaking, but consistent, pace. Agents reported 74,800 encounters last year and about 265,000 through September of this fiscal year. Medical examiners reported 239 sets of remains last year and 222 from January to September this year.

On a smaller scale, agents in Arizona reported similar totals for encounters in June and July, but the number of remains was dramatically different. Agents reported 30,800 encounters in June and 32,800 in July. But the remains of 52 migrants were found in June, more than twice the 23 found in July.

In fact, Border Patrol apprehensions plummeted by roughly 90% over the past two decades, while the number of remains found in Southern Arizona grew nearly tenfold.

Apprehensions in Arizona dropped from 725,000 in 2000 to 74,800 in 2020, while the number of remains grew from about 25 in 1999 to 239 in 2020.

Longer, more

perilous routes

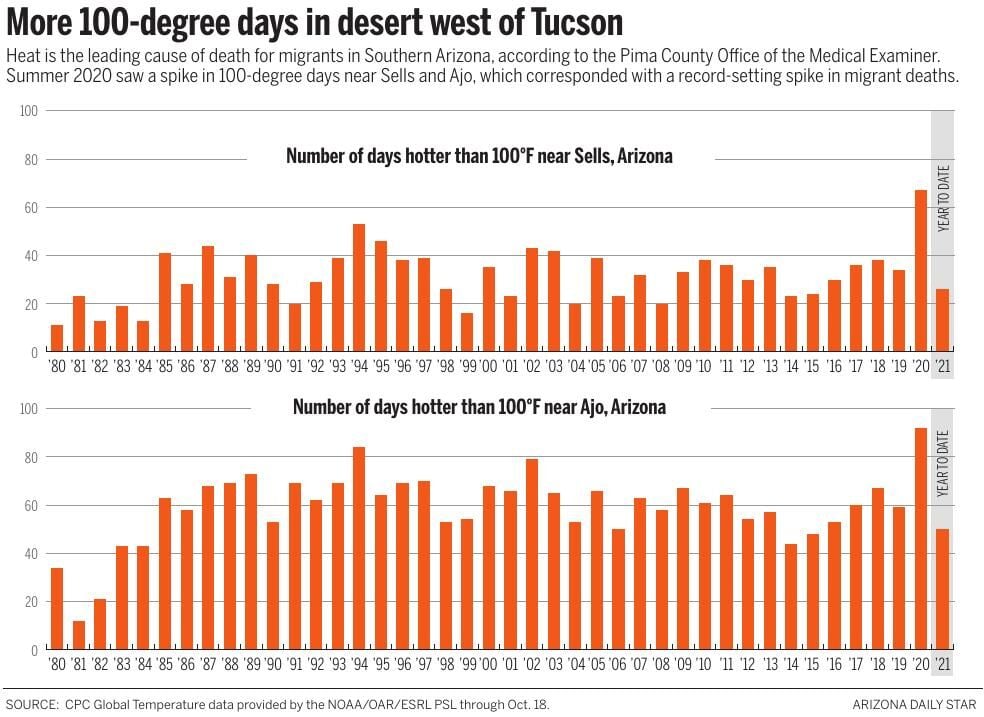

Deaths occur throughout the year and across thousands of square miles, but they are most frequent during the heat of summer and in the desert west of Tucson, the Star's geographical analysis of migrant deaths shows.

Two important trends emerged in the Star's analysis: Summers are growing hotter in Southern Arizona and migrants are taking longer, more dangerous routes through the desert.

A third trend, the quick expulsions of migrants to Mexico during the pandemic under the public health order known as Title 42, may have allowed migrants to make repeated crossing attempts just hours or days after making grueling treks through the desert. While Border Patrol statistics show Title 42 expulsions were the norm in the Tucson Sector in 2021, no data is available on how many of the migrants who died had been expelled.

More than 3,200 migrants died from exposure to the elements or their bodies were too decomposed for the medical examiner to determine a cause of death. The months from May to September accounted for 60% of remains found. For the roughly 1,400 sets of remains found within a week after death, more than 1,000 were found in the summer.

The risk for migrants is worsening as the deadly summer months in Southern Arizona grow hotter. Last year was the second-hottest year on record, as well as the driest, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Seven of the 10 hottest years on record were in the past decade.

In the cold winter months, migrants sometimes die of hypothermia, including about 60 since 2000.

Migrant deaths from violence have become rarer in Southern Arizona over the past decade. Fewer than 3% of all migrant deaths, or about 120, were the result of violence, such as gunshot wounds or stabbings. About 220 deaths were linked to vehicle wrecks.

A woman named Esthela disappeared in 2006 while crossing the border in Arizona "searching for the American dream," according to a video testimonial her sister Nadia provided in 2018 to the Colibri Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit in Tucson that helps identify migrants' remains and their families to find closure.

“She wanted to give her son a better future. School, clothes, food, everything that was very difficult, and is still difficult, to get in Mexico,” Nadia said. “She was an ambitious woman. She didn’t want to settle for how things were. She wanted to fight for more."

"I don’t know exactly how far Esthela walked. They think it was three days and that those days were very difficult for her, that it was terribly hot and perhaps Esthela wasn’t in the best health to walk,” Nadia said.

“I imagine that Esthela had to have suffered from thirst," Nadia said as her voice choked up and she wiped tears from her eyes. "Sometimes I think about that and it, that idea, thinking about that, that Esthela died thirsty. It tortures me, it hurts me.”

"Esthela had to have been aware that she wasn’t going to make it across the border or that she wasn’t going to survive," Nadia said. "How must my sister have felt in those moments?”

“I often tell my nephew Emiliano, I tell him, ‘Your mom gave her life for you, because she loved you.’ And I think, if my sister lost her life crossing the border it’s so that her son could be a successful man and could have a chance.”

“We didn’t come here to do bad things. We came because we want our kids to get ahead, for school, because there are more opportunities here to work,” Nadia said.

“And, I don’t know, I think that telling my sister’s story can help so that someone analyzes that, that perhaps there are laws that are too unjust and aren’t giving people a chance."

Already exhausted

upon reaching US

The journey across the border in Southern Arizona has grown longer and more dangerous over the last three decades, the Star's analysis of all migrant deaths on record in the state shows.

The trend is clear: Since 1990, the remains of migrants have been found in increasingly remote areas. Today, they are found much farther from roads, cities and towns than they were in the 1990s or 2000s, according to the Star's analysis of medical examiner data and OpenStreetMap data, a public geographic database.

In 1990, when relatively few remains of migrants were found, the average distance they were found from the nearest road was less than one mile. By the late 1990s and 2000s, that distance ranged from two to four miles, spiking to seven miles one year. Since 2010, the average distance from the nearest road ranged from five to eight miles away.

The shift away from towns and cities was also apparent, growing from an average of about three miles in 1990 to roughly 11 miles in the late 1990s and between 11 and 15 miles in the 2000s. Since 2010, the average distance ranged from 16 to nearly 20 miles away.

The Star analysis shows 43% of migrant deaths occurred in mountain ranges.

Border Patrol officials say migrants who try to evade agents are crossing the border in more numerous, but smaller, groups that require more agents to respond. At the same time, large groups of migrant families, unaccompanied children and other asylum seekers flag down agents, which pulls agents away from patrolling remote areas where deaths most often occur.

The dangerous routes smugglers choose to bring migrants across the border is a key reason for deaths in the desert, Border Patrol Agent Alan Regalado said.

Even before migrants reach the border, they may have walked for days or weeks and already are malnourished when they cross, he said.

"Their bodies just shut down when they go up the mountain," he said.

Suyapa Chacón shows a scar from a machete attack suffered in her home country of Honduras. The guide who smuggled her group into the United States promised a desert trek of no more than three days, but “it took us eight, nine days,” she said. She and her 11-year-old son were caught and sent back to Mexico.

When Suyapa Chacón crossed the border this summer, the guide who smuggled her group across the border said they would make it through the desert in three days.

"But when it came time, it wasn't three days. It took us eight, nine days," Chacón, a 29-year-old woman from Honduras, said in late July after the Border Patrol sent her and her 11-year-old son back to Nogales, Sonora.

They walked "sometimes all day, sometimes all night," she said inside the Kino Border Initiative shelter, a Jesuit ministry for migrants in Nogales, Sonora.

"At one point, we ended up without any food, any water," Chacón said. "Our shoes broke underneath and we couldn't walk, we couldn't keep going, but we had to keep battling because we had to get there."

"There were moments when I didn't think I would make it. I could feel that my heart was beating fast, I felt like I couldn't continue, but I had to arrive for my children," said Chacón, adding she "wanted something better for them."

She said she didn't know where she crossed the border, but recognized the names of several towns in Mexico west of Nogales.

'Funnel effects'

The increasing remoteness of migrant deaths the Star found in medical examiner data is in line with the conclusions of a study published by University of Arizona researchers in April, the latest in a series of studies on migrant deaths in Southern Arizona over the past 15 years.

Border enforcement policies pushed migrants into ever more remote and dangerous areas, leading to more migrant deaths, despite an overall decline in Border Patrol apprehensions, the UA researchers found.

Rather than walk for a day or two to a house or a highway and get a ride, migrants are walking farther and longer through the desert, said Daniel Martinez, a UA sociologist who has studied migration and migrant deaths since 2005 and co-authored the study.

“People today are crossing through some of the most remote and desolate areas of the Arizona-Sonora border,” Martinez said.

The UA researchers described "funnel effects" in which border enforcement policies in the 1990s pushed migrants away from cities like San Diego and El Paso to Southern Arizona. From there, border enforcement policies in the early 2000s pushed migrants away from Nogales and other Arizona border cities into remote areas.

The initiative to build up border enforcement in Arizona, dubbed Operation Safeguard by the Border Patrol, began in the mid-1990s, Martinez said. But the resources, such as fencing in urban areas, more agents, vehicles, and technology, didn’t arrive until 1999.

“It was the following year that we saw migrant deaths in Southern Arizona go from 15, 20 per year, up to 70, 79 roughly in 2000," Martinez said. "And by 2001, we had over 100 known migrant deaths in Southern Arizona."

The border security buildup in Southern Arizona was part of a wide-ranging strategy the Border Patrol put in place in the 1990s known as “prevention through deterrence.” The idea was to block urban areas and leave dangerous terrain as the only place where migrants could cross the border. If migrants instead crossed into busy urban areas, they could quickly blend in, making it harder for agents to spot and arrest them.

Federal officials acknowledged at the time that the strategy could place migrants in "mortal danger," as a 1994 planning document put it, but the thinking was that the danger would deter migrants from crossing the border. Instead, migrants continued to cross, and thousands died in the wilderness of Southern Arizona.

Over the past two decades, the number of agents in Arizona increased sharply, and a wide array of surveillance technology and border barriers was installed, including bollard-style fencing in urban areas such as Nogales, Douglas, Naco and Lukeville.

Border Patrol checkpoints dot most of the north-south highways in Southern Arizona and ring the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation. In many areas, surveillance towers stand on hilltops several miles apart from each other in a long row a few miles north of the border. Agents park in trucks with portable surveillance equipment and thousands of sensors alert agents when someone passes by.

Arizona was at the center of former President Donald Trump's plan to build a 30-foot-tall steel wall along the border in 2019 and 2020, accounting for about 225 miles of wall, or roughly half of all the miles of wall built under the Trump administration.

As a candidate, Joe Biden said he would not build another foot of border wall. Soon after taking office as president, Biden stopped wall construction, including an additional 20 miles of wall planned for Arizona's 370-mile long border with Mexico.

Body count is up

in unwalled areas

The Star has found statistically significant evidence that walls and pedestrian fencing have contributed to the funnel effect.

Using data from 2015 to 2020, the Star built two statistical models to examine how border walls and remoteness may impact migrant death counts.

The Star found cross-border migration corridors that have more of Arizona’s unwalled border also typically have more deaths than other corridors in a given year. Also, more deaths tend to be found in remote corridors.

To run the first model, the Star calculated the border miles by year that were unobstructed by the 30-foot-tall walls built during the Trump administration or the roughly 15-foot-tall pedestrian fencing built during previous administrations.

Then the Star calculated the number of border miles in each corridor by year that were unobstructed by these barriers.

Using these two numbers, the Star calculated each corridor’s share of Arizona’s unwalled border by year.

Our first statistical model estimates that a 1 percentage point increase in a corridor’s share of Arizona's unwalled-border typically increases deaths by about 4%.

For example, the migration corridor west of Lukeville currently has the smallest share of Arizona's unwalled border. Nearly all of it is walled off. Effectively, its share of Arizona's unwalled border is 0%.

Meanwhile, the corridor west of Nogales, where Sasabe is located, has nearly 4 miles of Arizona's unwalled border, which is about a 3% share of unwalled border across the state.

Based on data from 2015 to 2020, our model expects that the corridor west of Nogales would have 14% more deaths in a year than the corridor west of Lukeville.

The direction of this trend is apparent in the corridor in the eastern portion of the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation, where most deaths are currently found.

In 2015 it had about a 20% share of Arizona’s unwalled border. Since the new wall was built under the Trump administration, the share of the state’s unwalled border more than doubled in this corridor on the east side of the Tohono O'odham Nation, to 43%. No new wall went up on the reservation.

In 2020, 77 deaths were found in this corridor, or 50% more than in the corridor with the next highest death count.

This corridor has been one of the deadliest for migrants since 2000, however, so there are certainly other factors at play in addition to its share of the state’s unwalled border.

To run the second model, the Star took all the deaths in each corridor and calculated their average distance from the nearest town or city by year. We used this to measure remoteness. The model identified this trend: As distance from cities and towns increases, deaths counts in a corridor tend to increase, too.

The Star's models show that, from year to year, more deaths are typically found in corridors that aren't engineered to slow migrants on foot with walls, and more deaths are typically found in areas where migrants die more remotely.

While these models help us see statistically significant patterns in the data at hand, they don't establish cause and effect. Federal officials would need to make much more data available for researchers to build a highly predictive model that might anticipate where migrants will die.

Repeat crossings

follow expulsions

The vast majority of encounters with migrants in the Border Patrol's Tucson Sector result in quick expulsions to Mexico under the pandemic-related public health order known as Title 42. The Trump administration started using Title 42 in March 2020 and the Biden administration continues to use it.

The Border Patrol reported about 159,000 expulsions in the Tucson Sector in fiscal 2021 and about 32,500 migrants processed under immigration laws.

Customs and Border Protection's Air and Marine Operations works with Border Patrol to apprehend migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border on Nov. 10, 2021. Video by Danyelle Khmara/Arizona Daily Star

Title 42 is relatively new and needs more research, but it would be unwise to discount its effect on the increase in migrant deaths in Southern Arizona, the UA's Martinez said.

Title 42 expulsions are leading people "to engage in repeat crossing attempts that we haven’t seen since the early 2000s,” Martinez said, referring to the period when migrants often were sent to Mexico in what were known as voluntary returns.

“A lot of people are stuck at the border with very few options other than to try to cross again,” he said.

Michele Maggiora places flowers on a cross that marks where the remains of a migrant were found near Amado. She volunteers her time with Alvaro Enciso, who says he and his team have put up more than 1,000 crosses over the past eight years.

Planting crosses

The monsoon rains left the hills near Amado covered in greenery dotted with blue, yellow and orange flowers in early August.

Alvaro Enciso and a handful of volunteers trekked out to the desert west of Amado on a Tuesday morning, one of hundreds of trips Enciso has made in the past eight years to mark where more than 1,000 migrants died.

He makes wooden crosses and fits them with a red dot, as seen on the Humane Borders online map of migrant deaths, and an item left by migrants in the desert, such as the metal top to a jar. Guided by GPS coordinates, he and a handful of volunteers hauled wet cement in a bucket down a dirt road and into the meadow.

He puts crosses at the "exact point where someone's life, plans and dreams ended there. And that death caused a lot of repercussions and ramifications to a family south of the border, and maybe to a family here," Enciso said.

One of the crosses now stands in a meadow a quarter-mile from a dirt road east of Amado.

Using GPS coordinates, Alvaro Enciso and a handful of volunteers plant crosses marking the spot where migrants have died in the Arizona desert. His hope is that the markers provide families a gathering place where they can grieve.

After planting the cross, Enciso repeated a simple ceremony he and his companions had performed hundreds of times.

Peter Lucero, a fellow volunteer, hung a plastic rosary around the top of the cross and sprinkled the cross with water from a white plastic bottle, a nod to the Catholic faith of many migrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries.

As the gray clouds of a monsoon storm approached over the mountains to the west and the first raindrops started to patter onto the leaves of nearby trees, the group paused in reverence. Enciso pulled a worn notebook from his pocket and read aloud the name of the man who died at that spot: Juan Carrillo Gomez, 55 years old.

The crosses and ceremony mark a spot where a family can grieve. Countless other families of migrants who simply disappeared in the wilderness, their remains never found, are left to struggle to find a sense of closure.

Cesar Sanchez disappeared in the desert near Lukeville as he headed to Tucson for a job in construction in October 2016.

Cesar Sanchez disappeared in the desert near Lukeville as he headed to Tucson to work in construction in October 2016.

"Nobody can tell us what happened," said his daughter, Lilibeth Sanchez Alvarez.

Sanchez, 44, left his small town near Mazatlan, Sinaloa, on Mexico's west coast, hoping to find a better way to support his family.

He had worked as a police officer years before, but gave it up after he was threatened too many times. He started working as a carpenter and mason.

He waited in Sonoyta, a small town on the Mexico side of the border about 150 miles southwest of Tucson, with the guide who had smuggled several of his family members across the border two years earlier.

He called his daughter to say that he was getting ready to cross and he would call her in 10 days, Alvarez said. That call never came.

Alvarez called a family member, who had spoken to Sanchez during his trek. Sanchez had said he was getting tired in the desert. He knew there was a "button" he could push to call for help, Alvarez said, likely referencing the button on rescue beacons the Border Patrol places in the desert. But she didn't know if he ever made it to the beacon.

His family doesn't know if he is alive or dead, just that "he's not here anymore," she said. But they are becoming resigned to the idea they may never see him again.

"It's very hard to live with that idea," his daughter said.

Over the past two decades, the remains of more than 3,900 migrants have been found in Southern Arizona, with untold others dying, never to be discovered. The humanitarian disaster is intensifying anew, judging from the summer of 2021. Above, a wooden cross was erected in memorial to Maria V. Cortez in the foothills of the Baboquivari Mountains southwest of Tucson.