New legislation sponsored by Arizona’s U.S. senators would try to give a price break to customers of federal power across the West whose power costs spiked as water levels at reservoirs plummeted.

But before the bill could have its full impact, it’s very possible if not likely it would have to be accompanied by an infusion of federal tax dollars to hold down the cost of federal power to customers in Arizona and six other states.

The bill is aimed at easing a painful side-effect of the ongoing Colorado River water crisis: the boost it has spawned in electricity prices for nonprofit power customers, including cities like Tucson and Phoenix, the giant Central Arizona project, towns, tribes, farmers’ irrigation districts and power co-operatives.

As water levels have fallen since 2000 in reservoirs such as lakes Mead and Powell, due partly to climate change, less water runs through the dams’ turbines. Less electricity is generated. The lost energy must be replaced. That usually means buying replacement power on the private market at a sharply higher cost.

The bill, sponsored by Sens. Mark Kelly and Krysten Sinema of Arizona and Utah Rep. Celeste Maloy, would under certain circumstances direct the federal Western Area Power Administration to reduce rates paid by hundreds of power customers in the seven Colorado River Basin states, including around 100 operating in Arizona.

The rate cuts would take effect when power generation from Hoover and Glen Canyon dams, along with several others across the West, drops below specified minimum levels — levels Hoover and Glen Canyon have at least approached in recent years.

The power administration, commonly known as WAPA, manages power operations and sales for many major dams across the Colorado River Basin.

The Central Arizona Project is by far the largest buyer of Hoover Dam power. It provides 6% of the electricity CAP needs to pump Colorado River more than 2,900 feet uphill from Lake Havasu to Phoenix and Tucson. Other Hoover power buyers include local governments in Tucson, Phoenix and 20 other Arizona cities and towns. They take small slices of that power to pump, treat or otherwise move their water supplies around.

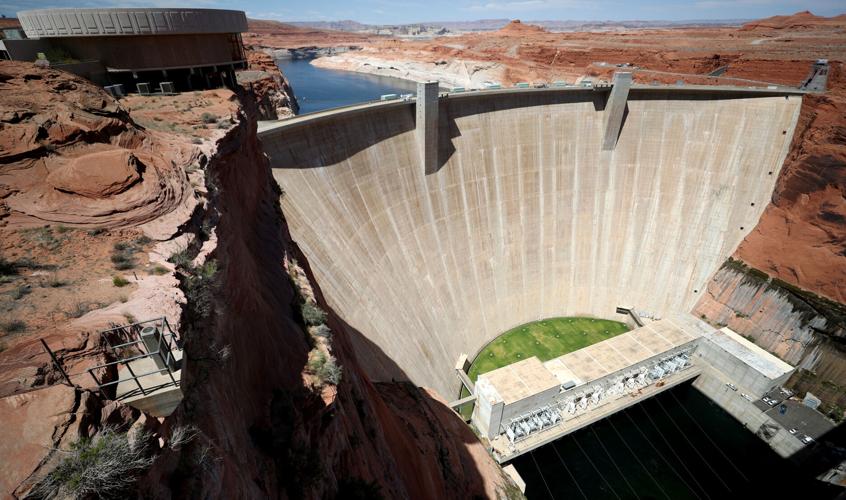

The electrical substation fed by hydroelectric turbines inside Glen Canyon Dam shown beyond Glen Canyon Bridge.

Hoover and Glen Canyon’s customers also include the Tohono O’Odham and Pascua-Yaqui tribes in and near Tucson, and the Navajo tribe and the Gila River Indian Community in northern and central Arizona, respectively. Ten Arizona tribes buy power from Hoover Dam. The Phoenix-based Salt River Project buys power from both Hoover and Glen Canyon dams.

Agreement on one thing

Introduced this month, the bill has support from several public power-related advocacy and lobbying groups, and from other groups representing customers of power from the dams, including some in Arizona.

But it’s viewed skeptically by some environmentalists and outside experts who say now isn’t the time to tamper with longstanding formulas for setting electric power rates.

“We’re saying, ‘Look, Congress has allocated how many billions of dollars to (the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for water already,’” said Leslie James, director of the Phoenix-based Colorado River Energy Distributors Association, referring to the 2021 and 2022 passage of federal laws pouring $8 billion into water infrastructure and drought relief.

“If Congress can do that for water projects, Congress can do that to assist hydropower,” said James, whose group represents consumer-owned electric systems including utilities and state power agencies in Arizona and six other Western states that buy power produced by Glen Canyon and other dams in the Colorado River basin.

But Kyle Roerink, director of the Nevada-based Great Basin Water Network, a conservation group, said this bill is the wrong approach to addressing the problems of declining power supplies from dams and escalating prices to power consumers.

“It kicks the can down the road, burdening already underfunded agencies and giving a veneer of normality to ratepayers. We need to begin climate adaptation and recognize that the hydropower goose never laid golden eggs,” said Roerink, whose group seeks to protect land and water resources in the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah. “This is an investment in the past, not the future.”

Where both power interest groups and outside observers agree is that this bill by itself won’t reduce electric power rates. To do that, WAPA also would have to find money elsewhere to make up the difference between what the power market would charge them for electricity and what their lowered rates would provide. That’s because the bill doesn’t appropriate any money.

David Wegner, a retired Reclamation engineer, and Eric Kuhn, an author and researcher and a retired water district general manager in Colorado, agreed that WAPA has no other money source besides its electric power sales revenue.

“You heard of that group called the American taxpayer? That’s where I suspect they’ll push it to. Who else are you going to go to?” said Wegner, who sits on a National Academy of Sciences board. “The only revenue source I know of is the American taxpayer.”

Where to get the money?

A WAPA spokesman, Stephen Collier, declined to predict where that money would come from.

“As a matter of policy, the Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) does not speculate on the potential impacts of proposed legislation. Our focus continues to remain on fulfilling our current mandates and commitments to stakeholders,” Collier said.

James of the Colorado River energy distributors’ group agreed that tax dollars will likely be needed to carry out the bill’s goals. The group also hopes WAPA can find additional money elsewhere in its programs. The bill’s intention was to give WAPA guidance to use its legal discretion to address this problem, said James, who said she was involved in drafting the bill.

“It does not come with money. That was the continuing issue that we’ve butted up against,” James told the Star.

If the bill had a price tag on it, the sponsors would have to find some way to offset the costs, she said. This way, “It doesn’t mean a big chunk of (new) money has to be spent. It could mean, ‘Are there some things you could defer? Are there some costs that could be allocated to a different purpose?’”

This bill has been in the works almost two years, said James.

“We’ve seen this coming. It’s just trying to find how do you do it, without going to Congress and saying give us a billion dollars, too. That’s just not going to happen.”

Future of system at stake

At stake in this debate is nothing less than the future of a federally subsidized and managed electrical power system that has provided and sold electricity to customers across the West at prices much cheaper than those sold on private markets. It has been able to because the feds don’t need to earn a profit.

The system dates to 1902, when the Reclamation Act creating the Bureau of Reclamation was enacted into law, spawning several generations of dam construction that included power generation as a side benefit.

“The whole basis of the federal power program was to develop the West, to provide water and power to energize the West, to provide resources so the West could develop,” James said.

A view from the Hoover Dam on the Arizona-Nevada border looking toward the O’Callaghan-Tillman Memorial Bridge.

Among the prime beneficiaries of the federal power are the 62 customers of the Arizona Power Authority. It’s a state agency charged with marketing Arizona’s share of the electricity generated by Hoover Dam at the Nevada border. Formed in 1944, it’s been selling Hoover power since 1951.

Besides its urban customers, the authority sells power to at least 20 irrigation districts that use it to pump groundwater for their crops. The CAP also benefits from sales of Hoover Dam power because the dam’s customers are assessed a tiny amount for every kilowatt hour of power sold to help repay the CAP’s $4 billion construction tab.

“The authority has worked effectively with both publicly-owned and privately-owned utilities in making Hoover Power Plant hydro power available to all major load centers throughout Arizona at the lowest possible cost,” the authority says on its website.

But since 2000, the dam’s power supplies have steadily declined as Lake Mead has fallen from being nearly full — just below 1,200 feet — at the turn of the century to levels as low as 1,043 feet at the end of 2022.

It has since rebounded to almost 1,070 feet due to last year’s heavy snows and high river flows. But this year’s forecast for the river is much gloomier, meaning the lake is expected to drop again. Under the most dire federal forecasts, it could drop as low as 1,037 feet in fall 2025.

As of Jan. 25, Hoover Dam was generating about 71% of its maximum power capacity, the bureau said on Friday.

At Glen Canyon Dam, power generation plunged to a record low during water year 2022 from October 2021 through September 2022. It jumped back 26% to produce 3.27 megawatt hours from October 2022 through September 2023. That difference between the two years could power 61,800 homes for a year, the bureau said.

But with 2024 shaping up as a drier year, the feds expect to release at least 10% less water from Powell to Mead for water tear 2024, ending Sept. 30. Glen Canyon’s power generation is also likely to decline again.

For the power authority, Hoover power’s decline has forced it to raise electricity rates to its customers by about 19% since 2019, said Jordy Fuentes, the authority’s executive director. Because Hoover power is sold at cost, with no profits made, it often costs the authority two or three times more to buy replacement power, he said.

“These are 50-year take or pay contacts” the authority has with the federal government to buy Hoover power, he said.

“Even if zero power comes, you still have to pay the dam operation costs. Hoover itself is about a $90 million a year budget. That has to be paid somehow.”

The new bill, which the authority supports, is a way of protecting hydropower customers, and insuring that people recognize hydropower’s importance, he said.

While it’s possible there may be some federal taxpayer costs to finance the bill’s goals, Fuentes notes that otherwise, the burden of finding and buying open market power will fall on local water ratepayers.

Most of Hoover Dam power goes to move water for its customers, “whether pumping it, pushing it around in canals or treating it,” he said. “If the higher power costs get passed onto customers like they traditionally have, and power keeps getting less, it will be passed onto customers’ water bills.”

Designed for the river of old

Kuhn, retired general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District based in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, said he doesn’t have a position on the new bill. But he notes that one reason WAPA has to raise customer charges is that it originally entered into “firm” contracts with customers that were supposed to guaranteed of getting a certain amount of power under most circumstances.

“Then when power is not available because a dam isn’t producing enough power, then they have to go on the open market and buy the power by law. One of the things that you might say is ‘well, you might have to require them make their contracts not firm, and make them subject to water availability’. That puts the burden on end users,” Kuhn said.

Passing the bill would lead to subsidizing power users, by paying the difference between costs of power on open market and cost of power produced by these dams, which were built a long time ago, Kuhn added.

“It’s like if you sold your house and if you have to buy a new house, the market is very different than what it would have cost you to buy a house 30 years ago,” he said.

The power administration “is in a hell of a mess,” he added.

It was created in the late 1970s during the administration of President Jimmy Carter to take over marketing of the hydropower from the river from the Bureau of Reclamation. Kuhn, who was involved in two rounds of negotiations with WAPA at the Colorado River District in the early 2000s, praises it as an agency that has always been helpful and straightforward.

“But they inherited a system that was designed for a river that no longer exists,” he said.

Letting power users off easy?

Concrete intake towers revealed by receding Lake Mead behind Hoover Dam in Nevada.

Retired Reclamation engineer Wegner doesn’t support the new bill, although “I understand why they are dong it; I don’t think you should let power users off the hook quite as easy as they are trying to push it.”

Because of the way Glen Canyon Dam has been operated, the power users and the generation of power have had a direct impact on endangered species and cultural and natural resources, said Wegner. “Just to let them off the hook without something in compensation, I don’t agree with that,” he said.

But James of the power generators association noted that revenues from federal power sales go to programs to help endangered species, control the river’s salinity and help pay off the costs of building dams built in part to serve farmers who otherwise couldn’t afford to repay them without federal help.

Plus, power revenues go towards repaying the dams’ federal construction costs, maintenance of the dams and insuring they’re reliable. This includes “black-start” capability, which allows interconnected plants to restart their own power without support from the electric grid in the event of an outage on the grid, she said.

“All these costs — increasingly expensive hydropower, operations and maintenance costs, replacement power, and replacement renewables — are passed on to customers by not-for-profit utilities who have no shareholders to generate revenue,” James said.

“Today, power customers are paying twice — once for the power purchases from the market, and once for fixed costs that are allocated even when there is significantly reduced power production.”

“Gaping wound”

Where all parties do agree is that the solution offered by the proposed legislation is temporary, because if temperatures keep warming and the reservoirs keep declining further, power costs and the need for federal subsidies will keep escalating.

John Weisheit, a Utah environmentalist who opposes this bill, calls it “a Band-Aid for a gaping wound.”

“The system was made to work with reservoirs that were functional. Our reservoirs are not functional, so how can you have functional hydropower?” said Weisheit, director of the Moab-based group Living Rivers.

James acknowledges the bill offers a short-term solution, and that the system will be rethought as federal and state negotiators hash out how the river and its reservoirs will be managed when current operating guidelines for it expire at the end of 2026.

“The hydrology is going to drive and the 2026 guidelines are going to drive what power gets,” James said.

Solar as replacement power

While these discussions continue, the power authority is working on a project to fill some of the hydropower gap, director Fuentes said.

It’s working with a Southern Arizona utility, the Arizona Electric Power Cooperative Inc., to seek a federal grant to build a large solar and battery storage project to furnish customers power from the sun instead of from the Colorado River.

A person is reflected in a window as they walk across Hoover Dam at Lake Mead near Boulder City, Nevada. The bathtub ring of light minerals around Lake Mead shows the high water mark of the reservoir, which had fallen to record lows.

The grant is being sought from a U.S. Department of Agriculture rural utility services program that’s financed by the 2022 federal Inflation Reduction Act. It would pay up to 25% of the project’s cost of “hundreds of millions of dollars,” he said.

“It’s meant to be replacement power for what we’re not getting,” Fuentes said.

Many of the authority customers working on the project also buy Glen Canyon Dam power and could use the new project to offset some of that lost power, too.

The project would be divided in two parts, he said. One would be built in Cochise County next to AEPCO’s Benson plant. The other would be built at a Central Arizona location Fuentes declined to disclose because the parties are negotiating with a large developer for a contract to build it.

“The project is gong to be very large. There’s a number of entities, probably 30-plus on that (authority customer list) who will be participating in it,” he said.

“We expect it to be signed in coming weeks,” Fuentes said.

“It really is an amazing project,” he said.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis explains what "dead pool" means as water levels shrink along the Colorado River.