They’ve been called everything from baby jails to summer camps, but an in- depth look at shelters for immigrant minors reveals a well-intentioned system that had to expand rapidly and that struggles with accountability and consistent monitoring.

The shelters — 100 nationwide — had been working largely out of the public eye until this summer, as news spread that the U.S. government was splitting families at the border and that some of the children were being housed there. Protesters started to show up and increased media scrutiny has since revealed instances of overmedication, sexual abuse and improper use of physical restraints.

In Tucson, the Arizona Daily Star reviewed nearly 100 incident reports to the Tucson Police Department from Southwest Key’s Estrella del Norte shelter, inspection reports from the Arizona Department of Health Services, and spoke with several current and former employees, as well as with long-time experts.

While advocates said the current situation is a vast improvement from prior decades, they added that efforts by the Trump administration to roll back protections for the minors can mean longer stays and increases the likelihood of something going wrong.

The changes, said Michelle Brané, director of the migrant rights and justice program at the Women’s Refugee Commission, shift the focus from the welfare of children to enforcement.

“All of this combined with larger facilities, more focus on the detention aspect compared to the case management and release aspect, is bound to have more problems,” she said, and to erode “a lot of progress we’ve made in the past 20 years.”

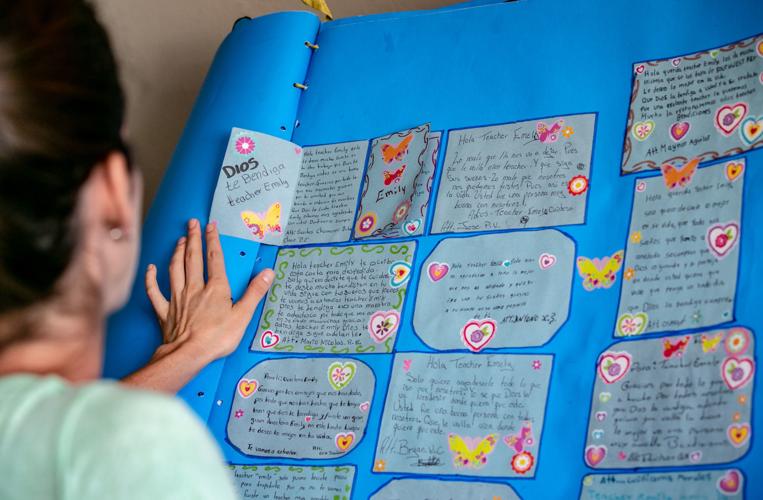

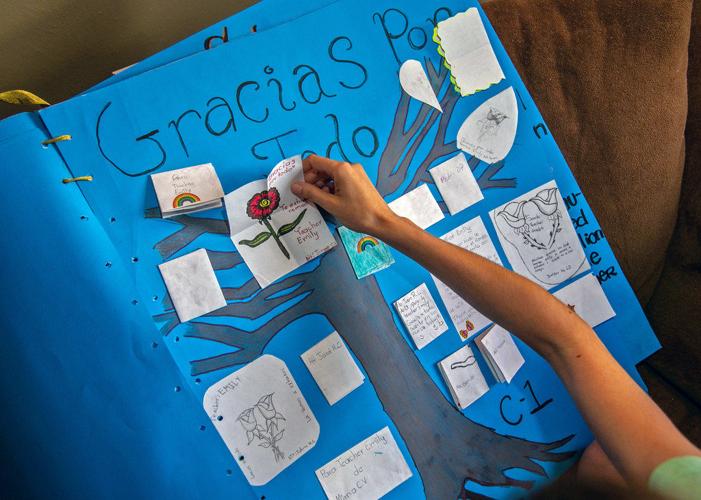

Emily Macaluso, a former teacher at Southwest Key’s immigrant shelter in Tucson, examines a collection of artwork and letters at her home. The collection includes items and writings the children made for her before she left the job.

In the spotlight

Used to housing older teens who crossed the border alone, many shelters were unprepared for the arrival this year of inconsolable toddlers who couldn’t understand why they were taken away from their parents.

“They would cry for three days straight, día y noche,” day and night, said a current Southwest Key worker in Tucson who asked that her name not be used because she fears losing her job.

A child whose father was deported “started to misbehave, getting desperate,” she said. He was at the shelter three months before being transferred elsewhere. She doesn’t know what happened to him.

There was also a 6-year-old boy who cried at the mention of his father. He wondered whether he had misbehaved so badly that his dad had abandoned him.

The Trump administration’s decision to criminally prosecute everyone crossing the border illegally — including parents traveling with children — led to the separation of more than 2,600 children.

The president signed an executive order in June halting the practice. But about 500 kids remain separated, in many cases because their parents were deported.

The arrival of dozens of traumatized children tested the ability of shelters to properly care for them, workers and former officials said.

The children were going through a rollercoaster of emotions. Some were very upset, with thoughts of their parents consuming them, while others adapted quickly, said Emily Macaluso, a former lead teacher at Southwest Key.

She remembers a little boy who was initially “chatting it up,” playing store at the library. “‘My mom always makes me atole, who is going to make it for me?’” he casually asked staff.

Then, during lunch, “‘I want my mom,’” the boy cried after taking a bite of something he didn’t like.

Some 300 immigrant minors are being held at a facility on Oracle Road where this demonstration was held June 28.

There were those who would kick and punch in outbursts of anger, with only some staff members knowing how to handle them.

The Tucson shelter, for instance, lacked age-appropriate toys, leaving children with not much to do for most of the day, one employee said. Eventually those children were transferred to Phoenix.

The shelter had rules, designed to prevent sexual abuse or harassment, that were at times applied mechanically to all children.

In one case, a group of three Brazilian siblings who had just been separated from their parents were huddled together and crying when Antar Davidson, who speaks Portuguese, was told to tell them they couldn’t hug. The former Southwest Key worker quit his job soon after.

“Separating children from their caregivers is something that is really disastrous for their emotional wellbeing,” said Michael Sulkowski, associate professor in the School of Psychology Program at the University of Arizona.

“You take them out of a supportive environment to an institutional setting where caregivers can’t love, nurture, have physical contact — usual things parents do with kids —and kids don’t know how to react,” he said.

Working with separated children was not new, former and current employers said; the difference was their ages and numbers.

In one case, to do the required assessment within 24 hours, an employee had to use the Disney cartoon “Sofia the First,” which she knew the girl liked and tried to assess her emotional needs between questions about the animated princess.

“I’ve read things like children being told if you are bad you will have to stay longer or if you cry you’ll have to stay longer, which are clearly not rules of the program, but sounds more like something staff might do when trying to maintain order under a lot of pressure,” said Mark Greenberg, former head of the Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families, which oversees ORR.

Even though nationwide only about 10 percent of the children housed at shelters were those separated from parents, he said, “the arrival of family separation children, in addition to being horrific for the families, was deeply disruptive for the shelters.”

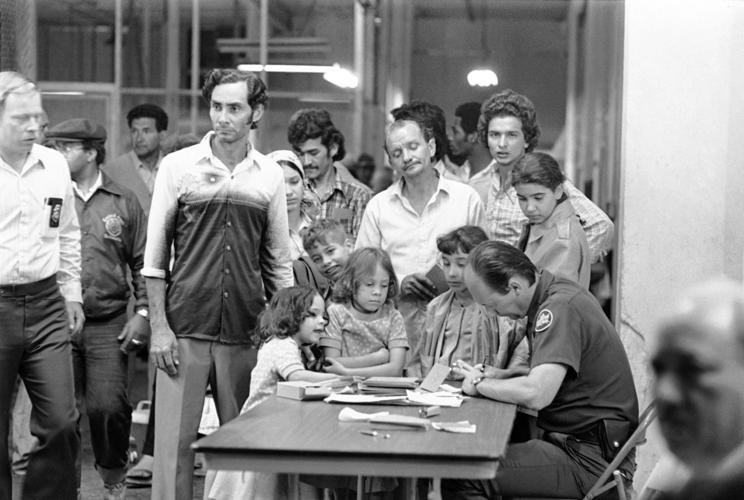

This US Border Patrol agent gets a close inspection by young Cuban refugees as they start their processing after arriving at the Key West Naval Base on Wednesday, April 30, 1980 from Mariel, Cuba. Waiting relatives either come to Key West or wait in Miami for their loved ones who escape Communist Cuba aboard packed yachts and trawlers.

How we got here

The country has struggled to care for unaccompanied minors for decades.

When Hungarians were fleeing Soviet invasion in the 1950s, the U.S. government lost track of many of the unaccompanied minors admitted under a refugee program “due to the lack of guidance and confusion among social welfare agencies,” according to the 2016 report “The Politics of Fear: Unaccompanied Immigrant Children and the Case of the Southern Border.”

Then, a surge in unaccompanied minors from Cuba and Haiti in the 1980s resulted in a policy where automatic detention was the norm and release the exception, wrote Sarah Rogerson, a professor at Albany Law School.

"A dangerous precedent for future waves of unaccompanied minors at the under-equipped southern border," Rogerson wrote, "and history would repeat itself again and again to the present day due, in part, to the lack of clear, consistent, and detailed guidelines for programs assisting unaccompanied immigrant children upon their arrival.”

At one point, about a third of the minors coming across were held in prison-like conditions under what was then the Immigration and Naturalization Service, according to reports from Human Rights Watch and the Women’s Refugee Commission.

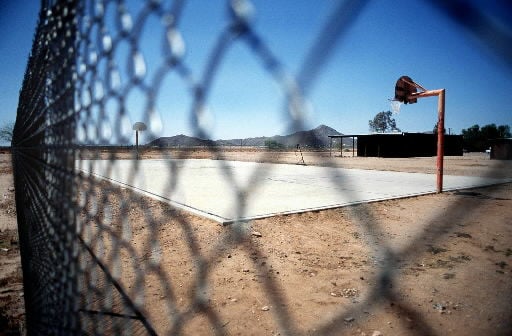

In this 1997 photo, the back of the Southwest Key Program Detention Center near Coolidge, Arizona, had a rusted pair of basketball standards in a barren field closed in by 6-foot high metal fencing.

Children were shackled, made to wear uniforms and housed with juveniles accused of murder and drug trafficking for months or years.

Until the early 1980s, there was no codified policy about the detention and release of unaccompanied minors.

It wasn’t until a class action suit that eventually became the Flores Settlement Agreement in 1997 that interim regulations were issued. Among other things, it called for children to be released to a parent, legal guardian or close adult relative. If that was not immediately possible, to be placed in the least restrictive setting appropriate to their age and needs.

About 20 years ago, Texas-based Southwest Key, which was founded in 1987 to provide services to minors in the criminal justice system, opened its first immigrant shelters.

One of them was in Coolidge, about an hour north of Tucson. The facility, with space for 48 children, is described in Star articles and reports as a nondescript two-story building on a rural road, surrounded by an eight-foot high fence, and monitored by electronic surveillance cameras and guards.

In a 1997 photo, a child from Kazakhstan holds on to her stuffed animal in a Southwest Key Program detention center near Coolidge, Ariz.

Researchers found children held for months without leaving the grounds, except for court hearings. Children were living in crowded conditions, with little free time and no personal privacy, which they said violated the terms of the Flores decree as well as international human rights standards.

“The hardest aspect of it for the children was that they were not just alone, but alone in a situation filled with uncertainty — none of them had any real idea what was happening in their case or how long they would be there. They were scared,” said Lee Tucker, one authors of the 1997 Human Rights Watch report and a current assistant federal defender in Tucson.

Things didn’t start to improve until after the government switched responsibilities for unaccompanied minors from INS to the Office of Refugee Resettlement in 2003. That's something human rights groups had long advocated for, arguing that children were arrested and removed by the same agency charged with protecting their rights.

The government started to transfer children to less restrictive settings and compliance with the Flores settlement improved with the help of the courts.

Things were far from perfect, advocates said, but they were moving in the right direction.

In this photo from 2014, two young girls watch a World Cup soccer match on a television from their holding area where hundreds of mostly Central American immigrant children were processed and held at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Nogales Placement Center in Nogales, Ariz.

Growth brings risk

As the number of minors continued to rise the system failed to keep up.

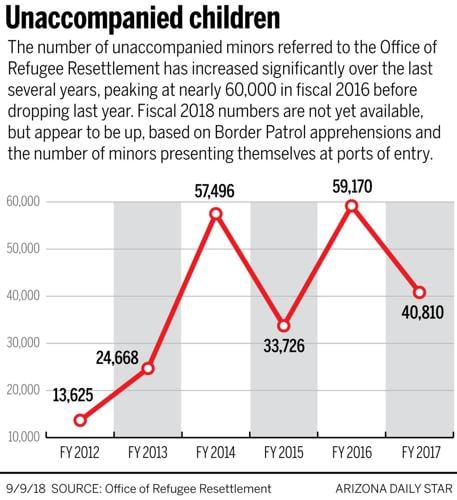

The number of unaccompanied minors referred to the ORR jumped from nearly 6,600 in fiscal year 2011 to 57,000 in fiscal year 2014, the highest number of children on record then.

The federal agency didn’t have enough space to house the teens and the law dictated Border Patrol agents transfer the minors 72 hours after being detained.

The summer of 2014, an old Nogales warehouse inside the Border Patrol station was converted to house the unaccompanied minors, and the government had to make use of temporary beds in Department of Defense facilities to meet capacity needs.

Southwest Key, which describes itself as the largest provider of shelter services to unaccompanied minors in the country, expanded. It converted an old studio apartment building into a shelter to house the minors in Tucson.

Over the years, the cost and number of facilities has also risen. In 2011, there were 59 facilities. Today, there are 100 operating in 17 states.

There are at least 13 facilities in Arizona, including eight run by Southwest Key, with a capacity of more than 1,600, according to public records obtained by Reveal and ProPublica.

In 2003, the program began with seven staff members and a budget of about $35 million, but today it costs more than a billion dollars. Southwest Key alone got nearly $500 million this fiscal year, with its CEO, Juan Sanchez, earning $1.5 million.

The number of children ORR is charged with caring for is hard to predict. Within one year, the number of minors in shelters across the country in any given day grew from 3,000 last year to more than 11,000 today. In 2002, that number was about 500.

Given the sudden bursts of growth, “it’s not surprising you have more incidents of abuse, more restrictive settings and less appropriate conditions,” said Brané with the Women’s Refugee Commission.

Former and current workers talk about having to wear different hats, especially during times when the numbers rise. They said some were hired without proper experience or adequate qualifications.

At one point, Southwest Key Tucson employees had 30 cases, which only gave them enough time to check in with the minors, until more workers were hired.

The rapid growth also led to larger facilities, which in the past has been connected to a rise in abuses. In 2009 researchers with the Women's Refugee Commission predicted that “problems related to providing care and safety in increasingly large facilities are likely to deepen as apprehensions continue to increase, unless DUCS (Division of Unaccompanied Children Services) begins to rely on smaller, more homelike facilities with better staff-to-child ratios.”

A converted Walmart in Brownsville, Texas houses about 1,400 minors. In Tucson, Southwest Key has capacity for 300.

“Detention settings are not ordinary or healthy environments and they don’t mitigate those risks, they increase those risks,” said Michael Bochenek, senior counsel on children's rights at Human Rights Watch, in reference to recent reports of abuse. He co-authored a 1998 report that looked at conditions in facilities for unaccompanied minors.

Although the system had worked fairly well for several years, wrote Rogerson with Albany School of Law, “under the stress of the recent waves of unaccompanied minors at the southern border, the weaknesses turned into failures.”

Overseeing the network of shelters for immigrant children is a constant challenge for the government.

Researchers have written in report after report about a lack of transparency and of inconsistent monitoring that puts children at risk, with conditions varying greatly.

While the Women’s Refugee Commission, in a 2009 report, commended Health and Human Services for its work, researchers said the ineffective system prevented the federal government from identifying facilities that were noncompliant and spotting warning signs.

Over the years, there have been issues with both, abuse at the shelters where the minors are initially housed and with the sponsors they are ultimately placed with. Neither seems to be new. A 1997 lawsuit filed in Tucson alleges a 6-year-old boy was molested at the Coolidge facility that year.

Levian Pacheco, a former Southwest Key youth care worker in Mesa was convicted Friday for abusing at least eight boys over an 11 month-period. ProPublica reported he worked four months without a background check.

Another Arizona staffer was arrested and charged with molesting a 14-year-old girl this year, The Arizona Republic reported. A 6-year-old girl who was separated from her mother this summer was fondled twice by another child at a migrant shelter in Glendale.

Locally, Tucson Police Department reports reviewed by the Star show at least three especially serious cases:

• Oscar Trujillo was convicted last year of sexual abuse and sentenced to three years probation for touching a 15-year old boy in his genital area over his clothing and trying to pull down his pants inside the teen’s room in 2015.

• A 17-year-old Honduran boy who arrived at the Tucson shelter in February 2017 told DCS that after he had surgery on his knee and while recovering and still on pain medication, he woke up and saw a staffer standing next to his bed and talking about his penis. Another time, the staff member reached for the video game controller and his hand brushed his genitals. The teen initially denied the allegations because he was afraid he would have to stay at the facility. The investigation is ongoing.

• In 2015, two female employees told managers that a maintenance supervisor had groped them. The company made an internal sexual harassment investigation and didn’t find anything. The maintenance supervisor denied the accusations and ultimately the case was closed because it was his word against that of the female employees.

Other reports point to allegations of inappropriate relationships with staff, sexual contact among minors and bullying.

In one case from 2015, a K’iche’ — a Guatemalan dialect — speaker complained that another teen would pull his pants down and hit his genitalia and that it had been happening over several days. The Department of Child Safety was called. Shelter workers said they would separate the teens and that the alleged perpetrator would have staff with him 24 hours a day.

In another case, a 16-year-old boy was accused of hugging a 17-year-old girl from behind and appearing to grab her breasts on several occasions. The girl didn't press charges and the manager told officers she would ensure the victim and suspect were away from one another.

Often, it was up to the minors whether they wanted to press charges. Only a few did.

Other incidents involve horseplay or minor allegations not uncommon in schools or foster homes, such as a teen patting a 16-year-old boy on the buttocks “as if it were in a congratulatory manner” during karaoke night.

In another, a staffer “hugged (the child) with one hand and with the other lightly tapped (the minor) on the butt,” when the 6-year-old was playing with her. The employee said “she was acting like she was spanking him” because he had misbehaved.

The reporter didn’t think there was anything sexual about it, but told officers they have to report everything, “even if they just give one of the kids a hug, they have to document it.”

But former and current employees point to inconsistencies in how incidents are handled.

Screen capture of a video provided to the Arizona Daily Star taken of children in the courtyard of a Southwest Key shelter in Tucson on June 19, 2018.

“If there’s bullying, we separate them,” a current employee said, “but then there are cases where a girl is being harassed by a boy in class and nothing happens. I don’t know how things fall through the cracks.”

None of the government agencies involved nor Southwest Key agreed to interview requests.

In an interview with NPR, Sanchez, Southwest Key’s CEO, said the company self-reports allegations and “if any allegation involves a staff member, we immediately suspend the staff member so they are out of the program, and we turn over the investigation to child care licensing.”

ORR wrote in an email any allegation of abuse or neglect is taken seriously and aggressively investigated. “Whenever appropriate, swift action is taken to address violations of policy, including initiating employee disciplinary action, termination, and reporting to law enforcement agencies and any relevant licensing bodies.”

The shelters are licensed by state agencies, but the state is only responsible for making sure the shelters comply with licensing requirements.

Since Southwest Key opened its shelter in Tucson, ADHS has conducted on-site investigations three times — twice in response to complaints and once when it applied to increase capacity.

One of the complaints from 2015 alleged children had been victims of molestation and that because of lack of local care, UACs (unaccompanied alien children) have spread chagas disease and that the facility was infested with lice. It was also alleged that the minors shared undergarments and received inappropriate food.

ADHS found the allegations to be unsubstantiated. While there had been a minor who reported inappropriate touching, the agency said police were immediately called and the employee was suspended and later fired.

After recent media reports of sexual abuse, the agency investigated all Southwest Key facilities and “was unable to substantiate multiple complaints regarding overcapacity, failure to report to law enforcement, staff qualifications, and the safety and care of children at Southwest Key,” Director Cara Christ wrote in a report to Gov. Doug Ducey.

But it found problems with employee background checks, especially in Tucson, where inspectors found eight employees were late to apply to have their backgrounds checked.

A 2016 Government Accountability Office report found lapses in the reporting and oversight, including required documents being missing and facilities going years without a monitoring visit. It recommended that monitoring be ongoing and “ingrained in the agency’s operations.”

In a written statement, ORR said that it has hired additional staff and put monitoring protocols in place to meet bi-annual on-site monitoring schedules since the report was issued. Shelters are also required to provide monthly and quarterly reports and file significant incident reports describing what happened and their response.

The lack of transparency troubles many, and advocates and researchers point to a long-standing lack of access to outside groups, including elected officials and the press. Tours have been arranged, but only under a tightly controlled environment where participants can’t talk with the children and photographs aren’t allowed.

The Star was able to enter Southwest Key in 2015, but only after Tucson City Councilman Steve Kozachik insisted that a member of the media be present. Even so, the tour had to be done under the condition that it would be off-the-record with questions answered later by an official in Washington, D.C.

“The fact we are talking about children is used as a further means of avoiding accountability,” said Michael Bochenek, with Human Rights Watch, echoing a point the group made in 1997.

“Suddenly child protection and privacy concerns are instrumentalized not to protect kids’ privacy but to shield the institution from scrutiny.”

Nearly 100 Tucson police reports reviewed by the Star show at least three especially serious cases of abuse at Southwest Key.

When days become months

The idea behind the shelters was to provide unaccompanied minors a safe space to live while the government worked to reunite them with their parents, or other sponsors in the United States, so they could continue their immigration case.

But they weren’t meant to be places where minors would linger for long periods of time. Currently, the average stay is nearly 60 days, up from 34 days in 2015 — and for some children it can be longer if they can't find a sponsor.

Members of the Trump administration want to overturn parts of the Flores Settlement Agreement and amend the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act, which they say handicap the government’s ability to detain and promptly remove unaccompanied minors.

Although children with families would be the most affected under a newly proposed regulation that would allow the government to detain children with their parents until their immigration cases are decided, experts said unaccompanied minors can also be impacted. There are sections that could impact the time Customs and Border Protection has to turn over the minors to ORR or whether county or state juvenile detention could be used in certain cases of emergency when there's no capacity at shelters like Southwest Key.

There are also reports of parents or relatives fearing coming forward after a recent policy change that requires the sharing of information between ORR and ICE, including fingerprinting of the potential sponsor and all adults in the household with no guarantee the federal government won’t use that information for enforcement purposes.

While this is a change from what recent common practice, it is not entirely new. In the 1990s and 2000s, human rights groups reported that INS required family members to provide information about their immigration status before releasing the children to them and in some cases used that against them.

“In any kind of group care setting, the longer children are there, the greater the risk that something may go wrong,” said Greenberg, the former federal official.

“The purpose of the program is to provide services and help to children, and that purpose gets completely undercut if ORR is being a partner with law enforcement,” he said, “and I think it’s increasingly happening.”

In 2014 and 2015, nearly 60 percent of children released from shelters were being released to a parent, he said. This year that figure fell to 42 percent and Greenberg thinks a contributing factor is parents either afraid or unable to come forward.

The longer the minor stays in the shelter the more they struggle. They worry about the deuda, the money their families borrowed for the journey north, they try to run away, or commit suicide, according to recent media reports.

“All of their emotions revolve around their case,” said Davidson, the former worker. “They lose a sponsor, gain a sponsor.”

They are also racing against the clock. Case managers and legal advocates try to find sponsors or alternatives for them before they turn 18, but if they don’t succeed, ICE agents immediately handcuff them and take them to an adult detention center. Based on prior reports and news articles, this appears to be a long-standing practice.

“You wanted to say, ‘Happy birthday,’ but everybody knew they were leaving,” said a former youth case worker.

To some, every day they remain in the shelter is a day they are not helping their families.

One 16-year-old started to show signs of depression. “He’s very quiet, very sad,” said the current worker. “Every time we have conversations and I ask ‘how do you feel? What’s on your mind?’ He says, ‘it’s la deuda.’”

His mother doesn’t have money to feed his siblings and he worries about how they are going to repay the 70,000 quetzales, roughly $9,000, for his and his dad’s crossing. The father was in immigration detention.

Since 2014, Southwest Key in Tucson has reported at least 16 runaways, six so far this year. Most are from Honduras and between 14 and 17 years old.

Police reports don’t generally say what becomes of them. In one case, a 16-year-old who fled on October 2015 was found later that month during an immigration raid in Utah and sent back to Honduras a few months later.

For the majority of the children, workers said, coming to a shelter was not their choice.

In the two years Emily Macaluso worked for Southwest Key, she heard painful and atrocious stories on a daily basis, said the 29-year-old.

Some children were abandoned by their parents. Others were fleeing gangs. There were those who had seen family killed in front of them or were raped on the way here.

A 16-year-old from El Salvador told her he had no friends because he had spent the last two years inside his home hiding from gangs. Then, he and his mother had been detained in Mexico and separated when they reached the U.S. border.

“I don’t know how much longer I can be here,” the teen would tell her.

At the same time, the kids acted just like any other teenagers, passing love notes in class, teasing each other, seeing how far they could push the teacher.

They are resilient — but they still need adults to protect them.

Emily Macaluso, a former lead teacher at Southwest Key immigrant shelter, examines a collection of artwork and letters at her home in Tucson, AZ on Sept. 3, 2018. The collection is bound in a book that includes items and writings the children made for her before she left the job.

What’s the alternative?

There’s a need for places where these minors can be safe while they are connected with their parents or sponsors, said Michelle Brané, with the Women’s Refugee Commission.

“For years we have found problems,” she said, but that doesn’t mean they should be shut down. “Could they be improved? Does it need to be monitored? Do we need more standards and more care put into it? Absolutely.”

Even the workers the Star spoke with, who said they were proud of the work they and many of their colleagues did, want to see change.

Macaluso would like to improve communication after the teens are released. Case managers do a 30-day follow-up call, but sponsors aren't always reached. There’s no talking with teachers or other community organizations to help them transition.

The company can do more to show workers they are valued, they said, and minimize the high turnover rate. About 400 people work at Southwest Key in Tucson.

“It takes a special kind of person to work there,” Macaluso said. “You eat with the kids, stand with the kid outside during PE. You have people come into classrooms all the time. Every day you show up and there are five more new kids who don’t speak any English. It’s a challenging position.”

She was always short a couple of teachers.

And just like any other place, there are those who are only there for the paycheck.

There were times when kids were moved and their personal belongings, like toothbrushes or bracelets they braided themselves, were lost.

"Basic things they shouldn’t be struggling with," the current employee said. At times, she heard from minors that they were told they were going to be reunited with their parents but instead were brought to Tucson.

“It’s a lie and it’s cruel,” she said.

Another former employee wishes they would step away from the increasingly institutionalized environment. “We are not supposed to ask them anything personal like ‘what did you do for fun? Where are you from?’” she said, adding that it often felt more like a detention center than a shelter. “People would break a lot of rules to be human, to make things better for these kids.”

Antar Davidson, who was among the first workers to speak publicly about the situation inside the shelters, would like to see more community involvement, as well as services and programs and better prepared staff.

“The system doesn’t prepare them from when they get out, it doesn’t set them up for success,” he said.

The Tucson Unified School District is also exploring options with Southwest Key to have its teachers educate the minors while they are at the shelter.

ADHS recently signed an agreement with Southwest Key that allows for more unannounced monitoring for the next year; mandate that they report to the state agency of all instances that “may present a risk or serious harm” to children and increased reporting on corrective actions; and requires the service provider to verify 100 percent of its current employees have valid fingerprint clearance cards within 30 days.

It's a step in the right direction but more needs to be done, said Kelli Butler, a Democratic state representative. She, along with other lawmakers, wants to tighten regulation, including through legislation.

They would:

- Require facility directors to notify both the state health department and law enforcement any time there are allegations of abuse.

- Add employees investigated and found to have abused or neglected children to the existing Central Registry database maintained by the Department of Child Safety, which catalogs proven cases of child mistreatment. A check of this database must be required during the hiring process for any residential treatment facility housing children.

- Consider the use of the Department of Public Safety online fingerprint check to screen employee applicants to decrease processing time.

- Increase fines for non-compliance, “both to incentivize better provider practices and to reimburse state agencies for the cost of investigations and oversight.”

- Give DCS statutory authority to investigate the well-being of children held within the immigration system, “but with the recognition that it may require an appropriation of funds.”

A new group called Uncage and Reunite Families, composed of elected officials, community activists and religious leaders, called last week on Gov. Doug Ducey to launch an independent investigation of shelters in the state, The Associated Press reported.

The group said the state health department’s investigation was inadequate because it only found issues with personnel records and delayed background checks for employees. The health department responded with a written statement saying it has limited jurisdiction but works with police to make sure abuse is reported and investigated.

Jeff Eller, a Southwest Key spokesman, told The Associated Press the organization fully supports expanded oversight of its operations and looks forward to working with state officials.

Human rights advocates would like to see more independent monitoring allowed.

“For the past 10 years we’ve been begging for funding to monitor immigrant shelters for minors and the response has been that the kids seem OK,” said Brané, with the Women’s Refugee Commission.

“Nobody is watching and look at what we found in Halfway Home (the 2009 report). We identified overmedication, use of psychotropic drugs, identified facilities too large, identified sexual abuse, lack of monitoring — all those things coming back as though they are new things people have discovered,” she said.

Progress has been made, she said, but increasing numbers of children in custody and growing political pressure will make the situation ripe for abuse.

“In a perfect world there wouldn’t be shelters but what is the alternative? Put kids in a law enforcement facility?” said a Southwest Key worker. “Kids will come no matter what.”

The public is not allowed inside the shelters that house minors who come across the border without a parent or legal guardian. But here’s what…