March broke records for the number of times officials apprehended migrants crossing the U.S. southern border, heightening the discussion and preparations around the approaching end to Title 42.

The public health policy, enacted in March 2020 because of the pandemic, allows officials to quickly expel migrants from the country without allowing them to enter into the immigration process, including those seeking asylum.

Earlier this month the Centers for Disease Control announced the policy would end on May 23 due to the current public health conditions and increased availability of vaccines and therapeutics to fight COVID-19.

There were more than 221,000 apprehensions at the U.S. border with Mexico in March, a 33% increase over February, according to Customs and Border Protection data released Monday — the highest monthly total in more than two decades.

While many are preparing for an increased number of migrants entering the immigration system, the number of apprehensions could possibly go down. One of the reasons the number is so high is actually because of Title 42. The rate of people crossing multiple times greatly increased since the policy was enacted, inflating the numbers, since more than half of the migrants apprehended were expelled under the public health policy.

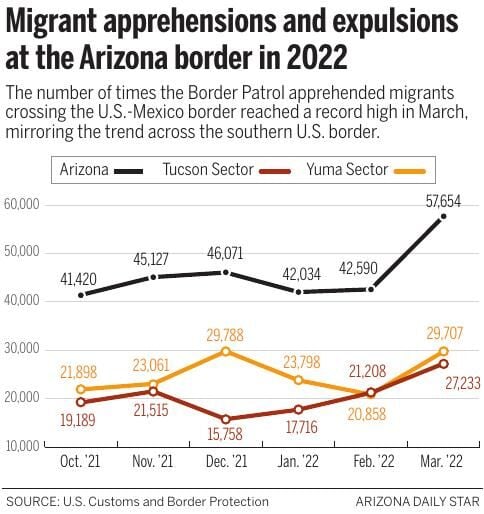

Arizona saw its highest monthly number as well in March, since at least October of 2019, at more than 57,600 encounters — at least 25% higher than any other month this fiscal year.

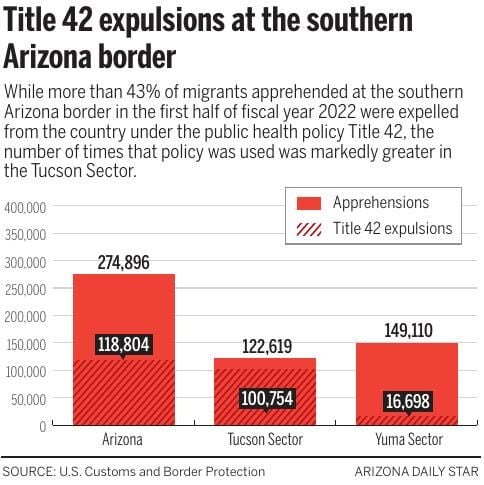

March marks the halfway point of fiscal year 2022, and there have already been nearly 275,000 migrant encounters on Arizona’s southern border, compared to about 312,000 in all of fiscal year 2021.

The Border Patrol’s Yuma Sector, southwest of Pima County and stretching into the eastern part of California, saw a huge increase in crossings that started last year, many involving families and mostly of people from countries farther away from the U.S., like Cuba, Colombia, Brazil, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela.

The Tucson Sector saw a substantial increase in March compared to previous months. In the Tucson Sector the majority of apprehensions involved single adults from Mexico.

What lies next

Migrants who are from countries farther than Central America are less likely to be returned under Title 42.

Of the migrants not expelled under Title 42, those who are deemed eligible to request asylum are processed by Customs and Border Protection, then sent to a local nonprofit that helps asylum seekers, which helps arrange transportation to a family member who is their sponsor in the U.S., typically in another state.

The Pima County Grants Management Department is putting together a budget with its community partners to address the anticipated surge of asylum seekers after Title 42 ends.

The county’s current expenses for the services it provides, which include food, shelter, transportation and other services, is $1.6 million a month, according to Regina Kelly, director of the Grants Management Department.

The county has been covering these increasing costs using grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, sometimes paying up front and then being reimbursed.

The $1.5 trillion federal spending bill that became law on March 15 included $150 million for FEMA’s Emergency Food and Shelter Program to assist migrants.

Pima received its first installment of $3.2 million from these new grants this past week, which officials anticipate will cover costs through June, based on current expenses. And if the the county is inundated with asylum seekers in June, it will ask FEMA for more money, Kelly says.

Along with the county’s plan to cover expenses, community partner Catholic Community Services is making adjustments to be able to receive more asylum seekers, says Teresa Cavendish, Catholic Community Services director of operations.

The nonprofit runs the Casa Alitas Welcome Center, where the asylum seekers typically go for a few hours or a night and can receive clothes, a shower, food, COVID tests and vaccines, and help arranging transportation to their sponsors.

All indications are that there will be a significant increase in the number of people needing assistance, especially in the Tucson Sector, Cavendish says.

The Tucson Sector is likely to see a bigger change than in the Yuma Sector because Title 42 is being used in the Tucson Sector at a far higher rate.

Of the 122,600 apprehensions in the Tucson Sector this fiscal year, 82% were expelled under the policy. Conversely, in the Yuma Sector, only 11% of the 149,100 apprehensions resulted in a Title 42 expulsion.

When the Department of Homeland Security is no longer expelling people under Title 42, it will process those who are unable to establish a legal basis to remain in the United States, such as a valid asylum claim, for removal under immigration laws.

As well, if the number of people coming into the immigration process increases, there will likely be more people in immigration detention and prosecuted through the courts. Neither the District of Arizona U.S. Attorney’s Office nor the courts would comment on whether they are anticipating higher numbers or whether there is preparation taking place.

With the increasing number of apprehensions at the border, some politicians have called for Title 42 to continue, including both of Arizona’s U.S. senators, Democrats Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema.

“It’s unacceptable to end Title 42 without a plan and coordination in place to ensure a secure, orderly, and humane process at the border,” Kelly said in a statement on April 1, following the announcement to end Title 42.

“From my numerous visits to the southern border and conversations with Arizona’s law enforcement, community leaders, mayors and nonprofits, it’s clear that this administration’s lack of a plan to deal with this crisis will further strain our border communities.”

The Department of Homeland Security says it does have a plan. Congress recently appropriated $1.45 billion for a potential surge of migrants at the southern border. The DHS plan includes additional resources to increase the holding and processing capacity at the border and to remove those who can’t prove a valid claim to stay in the states as well as working with other countries to address root causes of migration.

Many who say Title 42 should not yet be rescinded talk more about needing it for border security instead of its intended purpose as a pandemic precaution.

Kelly and Sinema are part of a bipartisan group of senators who are asking for more details and introduced legislation earlier this month to delay the end of Title 42 by at least 60 more days to give agencies more time to develop plans to deal with a possible influx of migrants.

Also, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, who is running for the Senate, is one of three Republican attorneys general suing the Biden administration over the decision to end Title 42.

“If Title 42 ends, it will result in an even greater crisis at the border that will have a devastating impact, not just on border states, but across the country,” Brnovich said in a tweet earlier this month.

Unequipped towns

Betto Ramos, coordinator at a migrant resource center and a migrant shelter in Agua Prieta, Sonora, says the number of people they are serving has greatly increased over the last year and especially in recent months.

In the nearly 16 years they’ve been operating, they’ve received more than 80,000 migrants, out of which more than 30,000 were in 2021, and 14,000 have been in the first three months of 2022. They’re currently serving about 200 people a day, though sometimes more, like last Monday, when about 80 people arrived every four hours.

When Title 42 ends, Ramos thinks the number of migrants they serve will go down. People will likely not be crossing numerous times and will be more likely to be deported to their home countries if they are not allowed to stay in the United States.

The resource center and shelter, which are partners of the binational Presbyterian border ministry Frontera de Cristo, don’t have a position on Title 42, Ramos says.

“We know that the policies only get stricter,” he said. “After Title 42 is lifted, people who are migrants will suffer more. … All the policies in both Mexico and the United States, in my experience, do not favor the immigrant population.”

Not all migrants arriving in Agua Prieta, south of Douglas, Arizona, attempted a crossing there. Some are transported by Customs and Border Protection from Nogales or Sasabe, which are 100 to 200 miles away, and dropped off at the border.

One of the reasons the number of encounters has increased in the last two years is actually because of Title 42. The count is the number of times Border Patrol apprehends someone crossing the border, rather than the number of people apprehended.

While there were more than 221,000 encounters on the entire U.S. southern border in March, nearly 56% of those people were expelled under Title 42 or immigration law, according to court documents.

Since many migrants are dropped off right on the southern side of the border, often in small towns that have few services for them and might be more than 100 miles from where they crossed the first time, many try to cross again, inflating the number of apprehensions.

In 2021, 27% of encounters at the northern and southern U.S. borders were with individuals apprehended more than once by the Border Patrol. The figure was 26% in 2020 but only 7% in 2019, prior to Title 42.

Many migrants are coming now because of different issues in their countries of origin, Williams says.

Political and economic distress, violence and natural disasters, which in many cases have been exacerbated by the pandemic, are forcing more people to leave their countries of origin that are farther away, such as Haiti, Cuba countries in South America. As well, the pandemic has made it harder for people to migrate to South American countries or for migrants already established there to stay.

Those in favor of ending the policy, like the Kino Border Initiative, a binational organization that provides humanitarian aid to migrants in Nogales, Sonora, say it subverts migrants’ rights under both domestic and international law to make an asylum claim, and that it leaves migrants to wait in border towns in often dire and dangerous conditions.

There are about 700 migrants in Nogales who have are waiting for the chance to ask for asylum, about 500 of whom have been waiting more than six months, says Joanna Williams, executive director of the Kino Border Initiative. Williams estimated that 75% of people waiting are families.

“Ending Title 42 should be done because it’s a moral issue,” Williams said. “It should be done because of the humanitarian issue, because just on a basic level, we need to have a system in which we operate within the law. And the law says that people should have access to asylum and therefore there should be some channel for that.”