Despite some recent headlines you may have read, scientists from the University of Arizona did not discover alien life on one of Saturn’s moons.

But they didn’t exactly not discover it, either.

In a new study published in Nature Astronomy, researchers from the UA and Paris Sciences & Lettres University said they couldn’t rule out the possibility of microorganisms on Saturn’s water-spewing moon Enceladus, where hydrothermal vents appear to produce conditions that could support such microbes.

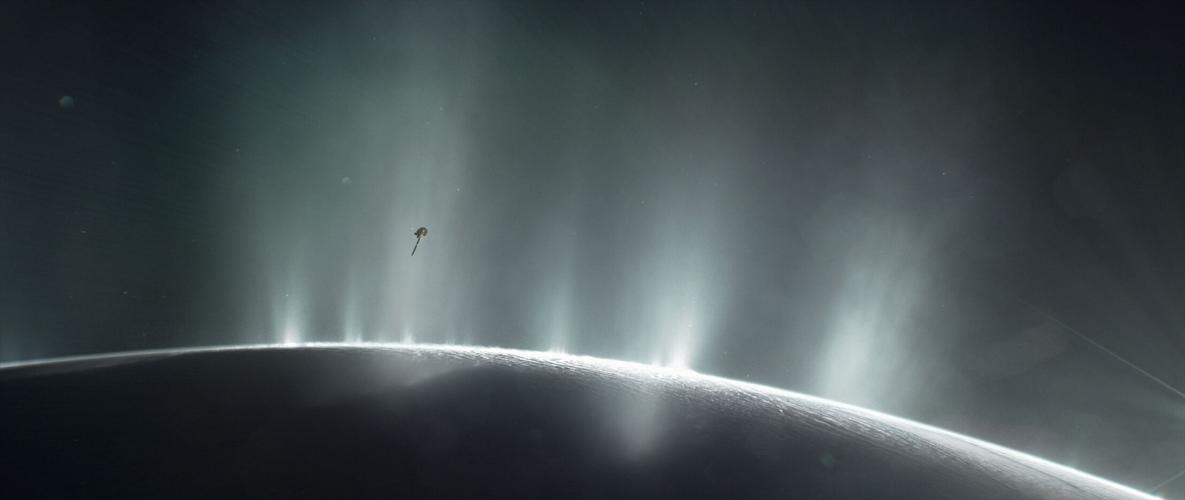

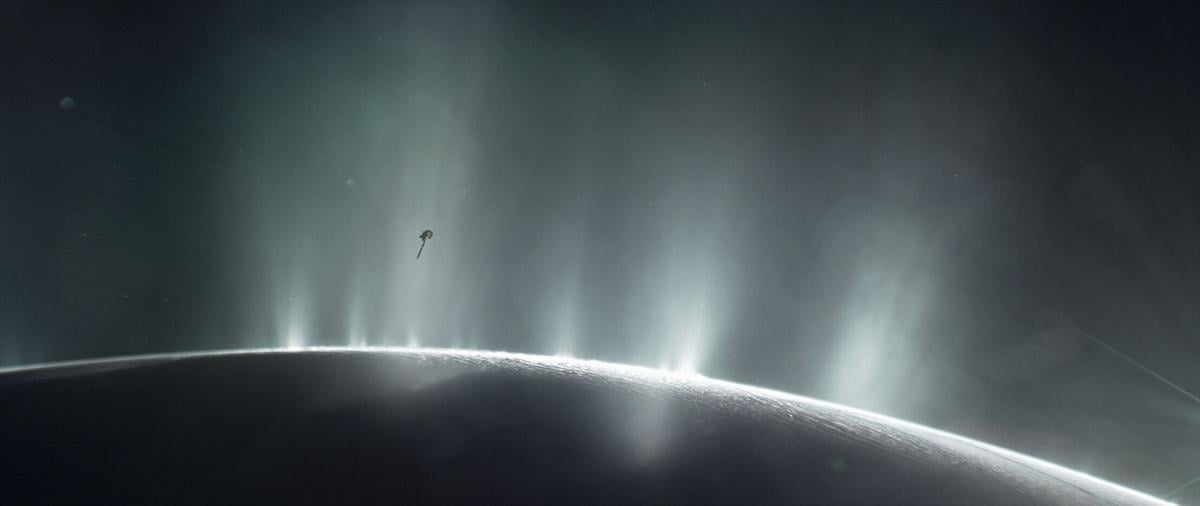

Their findings are based on a new analysis of data collected by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 2015, when it flew through one of the moon’s icy eruptions.

“Obviously, we are not concluding that life exists in Enceladus’ ocean,” said UA associate professor Régis Ferrière, one of the study’s two lead authors. “Rather, we wanted to understand how likely it would be that Enceladus’ hydrothermal vents could be habitable to Earthlike microorganisms. Very likely, the Cassini data tell us, according to our models.”

Since the study was published last month, it has gone viral on the internet, where summaries on science websites have given way to more sensational reports from other media outlets.

“I think it’s going a little crazy at this point,” said Ferrière, a theoretical ecologist whose connection to the UA dates back almost 30 years.

The giant geysers erupting from Enceladus have long fascinated scientists and raised questions about the vast ocean thought to lurk between the moon’s icy shell and rocky core. When Cassini flew through one of those plumes, it detected unexpected levels of dihydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide — molecules commonly associated with hydrothermal vents found deep in Earth’s oceans.

“We wanted to know: Could Earthlike microbes that ‘eat’ the dihydrogen and produce methane explain the surprisingly large amount of methane detected by Cassini?” Ferrière said.

With no way to sample Enceladus’ deep-ocean vents directly, researchers used new mathematical models to calculate which processes were most likely responsible.

Ferrière said the data is “easier to explain if you assume (microbial) life is there,” though scientists could also be seeing the results of some inorganic chemical process unlike any observed on Earth.

“In other words, we can’t discard the ‘life hypothesis’ as highly improbable,” said Ferrière, who works in UA’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “To reject the life hypothesis, we need more data from future missions.”

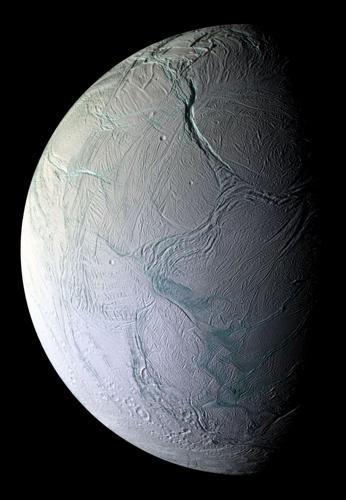

This mosaic of the surface of Enceladus was captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 2008 after the probe passed within about 15 miles of Saturn’s icy, water-spewing moon.

No such mission to probe the ocean on Enceladus is currently planned, and staging such a feat could take decades or even centuries, Ferrière said.

Until then, he expects his team’s mathematical model to be put to work to help determine the habitability and the probability of life elsewhere in the solar system and beyond.

Ferrière said he is now at work on a project aimed at adapting their methodology for use in studying so-called “alien Earths,” namely exoplanets orbiting other stars in our galactic neighborhood.

Cassini was launched in 1997 and orbited Saturn for 13 years.

Planetary scientists from the UA and the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson played major roles in the mission, helping to build and operate instruments onboard the spacecraft and its Huygens Probe, which landed on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, in 2005.

Originally, Cassini was expected to spend four years exploring the ringed planet and its moons, but NASA extended the mission twice before ending it for good in 2017 by crashing the probe into Saturn’s upper atmosphere. Ironically, the spacecraft was destroyed to prevent it from possibly contaminating the planet’s moons with any stowaway microbes from Earth.

Ferrière said this is the first time in his career that one of his papers has touched off so much media “buzz.”

He said the researchers, their journal partners and the UA’s communications team all took great care to convey the findings in a clear and measured way, but that does not come through in some of the more splashy news stories he has seen.

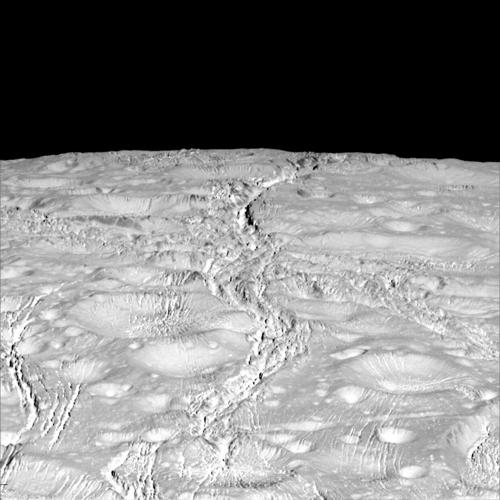

A close-up view of Enceladus’ north pole, captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft as it zoomed by the moon of Saturn on Oct. 14, 2015. Though no life has been detected there, new research suggests that thermal vents beneath the moon’s ocean could produce habitable conditions for microbes.

“Excitement (about scientific discovery) is a good thing,” Ferrière said, because it can increase public support for research and inspire more young people to pursue careers in science.

But overblown — and ultimately incorrect — reports about amazing new discoveries can also “hurt the credibility of the work,” he said. “It’s really important that we keep that enthusiasm under control.”