As Americans live longer, an increasing number of older adults are having to care for their even older parents at a time when both generations face health declines, memory issues, physical limitations and financial hardships.

The situation, caring for frail parents in their 90s and early 100s, can be daunting while the caregivers themselves are in their 60s or even 70s. The situation is forcing older adult children, some of them at or nearing retirement age, to decide if they are physically, mentally and financially capable of caring for a parent at the end of their lives.

Some take on the role of primary caregiver — reflecting how they were once cared for as a child by their parent; others must make a difficult decision to place their elderly parent in a care home.

About 10 percent of adults ages 60 to 69 and 12 percent 70 and older provide some type of care to their parents, according to a study by research economists Gal Wettstein and Alice Zulkarnain at the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. This compares to about 5 percent of adults ages 30 to 49.

About 17 percent of adult children care for their parents at some point in their lives, and the likelihood of doing so rises with age, the study reports. “As baby boomers enter their 80s, a large increase in the demand for long-term care is likely, with a commensurate rise in the reliance on care from their children,” the study concluded.

Any time a child must care for an elderly parent, the challenges can be daunting. According to a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, caregivers providing for persons with high-burden diseases, such as cancer or dementia, experience “high psychological stress” and “report an average of nearly $7,000 in out-of-pocket costs associated with caregiving each year.” Also, the Retirement Research study shows the time commitment for care gets longer as the adult child get older, with adults in their 70s spending about 95 hours a month caring for a parent.

The situation is not likely to change in the coming years: The U.S. Census Bureau projects that by 2030, “All baby boomers will be older than age 65. This will expand the size of the older population so that one in every five residents will be retirement age.”

It also projects that by 2035, for the first time in U.S. history, older people will outnumber children. Jonathan Vespa, a Census Bureau demographer, predicts “78 million people 65 years and older compared to 76.7 million under the age of 18.”

Carmen Soto takes a moment to enjoy the flowers outside her kitchen window.

Siblings become team to aid mother

Tucsonan Norma Soto-Ramirez, 61, retired early from her job as an educator to help take care of her centenarian mother, Carmen Soto. Norma, one of seven children, said she and her siblings were unanimous in their decision to work together to keep their mother safe in her house.

Norma also was a caregiver for her father, the late Miguel D. Soto, who worked as a miner and truck driver. The siblings, now ages 59 to 73, gave strength to their mother and one another after their father suffered a massive stroke in 2000, dying in 2012 at age 90.

They continued caring for their mother, who was diagnosed with dementia in her late 80s and also suffers from anxiety. Her vision and hearing aren’t as sharp as they used to be, and she uses a wheelchair.

Son Juan Soto, 64, an educator who also retired early to help care for his mom, said her health significantly declined after their father’s death, and it was decided to hire a caregiver to spend nights with her while siblings helped during the day.

At one point, her medication for anxiety was causing her to worsen to the point where she “broke a window to escape from the house,” recalled son Henry Soto, 70. “She would not sleep at night. In the day, she would stand at the gate outside yelling for help for 45 minutes. She would try to climb over the fence. It was very stressful,” he said, noting that one caregiver quit because of the frightful episodes.

“I dreaded coming here,” said Mike Soto, 71, of his shift to watch his mother. “We looked at assisted-living homes.”

Another meeting was called among the siblings to try to decide how to best care for their mother.

“We wondered and questioned, could we do this — care for her and keep her safe?” recalled Norma, informing her mother’s physician about her behavior.

Carmen Soto plays impromptu patty-cake with her son Mike as her other children, including Norma Soto, watch. The seven siblings, ranging from 59 to 73, take turns caring for Carmen.

After a few months, her medication was changed, and Carmen’s level of anxiety dropped, allowing her to remain at home.

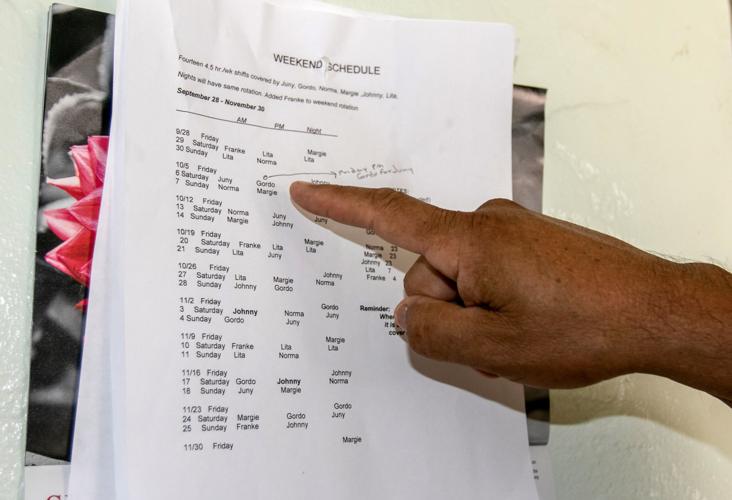

“We relied on each other and learned as we went along,” said Norma, pulling out a logbook where each sibling documents what occurs on their shift, including their mother’s appetite, sleep patterns, activities and visitors.

Her mother took steps earlier in life to help her children carry out her wishes as she aged. On the refrigerator door at her home is a “do not resuscitate” order Carmen signed in 1998. She also made a living trust, a will and put Norma in charge of her medical decisions.

As more siblings retired, they began rotating shifts to stay with her around the clock and paying for an extended family member to stay with her at night when needed. Daughter Angie Jessup, 69, travels from Avondale to Tucson to stay with her mother on weekends.

“I find strength in the love I have for her. Love gives me strength. She did so much for me. It is our turn now to do for her,” said Juan. “It is not a burden. It is a blessing caring for her. I was the last one to retire, and one of the reasons was because I wanted to be a part of this rotation.”

Carmen Soto’s grown children keep a schedule they follow on the wall of her kitchen in Tucson. The siblings, who range in age from 59 to 73, rotate their schedules to care for their mom in her home around the clock.

“Everyone is pulling their weight,” said Mike. Brother Henry explained that in most families the work falls on one or two, but splitting the work among seven makes it easier.

Carmen, who will turn 101 on Dec. 1, has outlived her savings but receives Social Security. The siblings pitch in a total of about $200 a month to supplement her needs, said Mike.

Caregiver services available

In 2016, the Pima Council on Aging surveyed 2,269 people ages 60 and older and found that 17 percent were unpaid family caregivers for an older family member, neighbor or friend, and 22 percent of the caregivers surveyed had no one to assist them, said Adina Wingate, an agency spokeswoman.

Respite is a complicated concept for a lot of caregivers who are too often the sole care provider, according to PCOA caregiver specialists. “However, taking a break from daily caregiving responsibilities is a tenet of self-care, and is available through PCOA family caregiver services,” said Wingate.

Pima County demographics show 25 percent of all residents are age 60 and older. In 2017, Arizona’s population was estimated at 7 million, and by 2020, one in four Arizona residents will be 60 or older, according to state projections.

Jason Browne, a home-care coordinator at Lutheran Social Services of the Southwest, offers his expertise at family caregiver training sessions held at PCOA.

“It is a wonderful role to answer the call as a caregiver,” said Browne. “When caring for others, it’s critical that you first take care of yourself. By not doing so, you put yourself at risk of exhaustion, health problems and even total burnout.”

He advises caregivers not to be afraid to ask for help and call on community agencies for resources.

Browne’s session also includes tips on managing time well, prioritizing a to-do list and how to deal with loved ones afflicted with Alzheimer’s. He teaches caregivers how to make rooms safe by having clear walking paths, plenty of lighting and grab bars in a bathroom. Attendants also learned how to sponge-bathe a person in bed, safely use medical equipment and how to correctly transfer a person into a wheelchair or vehicle.

Sharon Valencia takes care of her 90-year-old father, Ambrosio Jaramillo, a World War II and Korean War veteran who lost a leg to diabetes.

She Quit job to become dad’s caregiver

Two years ago, Sharon Valencia quit her job as a legal secretary because she chose to care for her dad, Ambrosio Jaramillo, a decorated Army veteran who served in World War II and the Korean War.

Jaramillo, 90, lost his left leg to diabetes in 2017. He did not get a prosthesis because he suffers from Parkinson’s disease, a progressive nervous-system disorder that affects movement, making it impossible for him to stand, Sharon explained. He also suffers from dementia.

Sharon looks at her father and remembers when he weighed close to 200 pounds, worked for a chrome company and was a baseball umpire.

He now is down to about 140 pounds and traveling to his native Los Lunas, New Mexico, to see high green country and the Rio Grande is not easy.

During his four-month stay at the VA hospital after the leg amputation, Sharon learned to care for her father, including dealing with a catheter that empties his urine into a bag, how to use a Hoyer lift to transfer him in and out of bed, and from his wheelchair into his recliner or to the shower chair.

She helped her older sister, Darlene Ramirez, who had been the primary caregiver since 2015. The roles switched when Ramirez was diagnosed with colon cancer and died last year.

Sharon Valencia, takes care of her 90-year-old father, Ambrosio Jaramillo and 89-year-old mother, Lucy Jaramillo in Tucson, Ariz. on Sept. 25, 2018.

“I had already been taking care of him. I knew his needs. It only made sense I do it full-time,” explained Sharon, who receives help from sister, Bertha Speer, 59, who gives Sharon a break on Sundays. Their brother, Gilbert Jaramillo, 64, a retired warehouse worker, and his two daughters and other relatives also help when needed.

Sharon does the care six days a week, from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m., and receives help from health-care aides contracted for 14 hours a week by the Department of Veterans Affairs. A nurse goes to the Jaramillo home near the University of Arizona once a month, or more often if needed, to give Ambrosio a check-up. Every three months, an occupational therapist, dietitian and social worker visit the home.

Sharon, a strong, fit woman, said she is able to care for her father because the VA provides his medication, medical supplies and the equipment that is required for his care at home. In addition to the Hoyer lift, the equipment includes a hospital bed, custom-made wheelchair and shower chair, and an outdoor ramp.

“Sharon is wonderful,” said her mother, Lucy Jaramillo, wiping away tears. “They all are wonderful and help out so he can stay at home.”

Lucy turns 90 next month and is in good health, but uses a walker outdoors because she fears falling. She cooks all the meals, pureeing foods or cutting pieces small enough for her husband to swallow.

Ambrosio’s body is sensitive, especially when moved from one location to another. He wears gloves to keep his hands warm because of circulation problems. Sharon administers his medications daily, including eye drops for glaucoma and pills to control his thyroid, cholesterol, blood clots, diabetes, dementia and Parkinson’s.

“I have trouble letting go,” said Sharon, who is meticulous about her father’s care.

“I was kind of hesitant to accept the health-care aides from the VA because I didn’t know if I could trust them to take care of my dad,” she said. “Now, I am glad I did.”

A portrait of the children of Ambrosio and Lucy Jaramillo at their home in Tucson.

”Mom deserved the best I could give her”

Two older adults who cared for their aging parents until their recent deaths have no regrets. They received support through Pima Council on Aging programs, including caregiving training sessions with Lutheran Social Services.

“My mom deserved the best that I could give her,” said Bruce Woodward, 61, a manager at a car audio installation and window tinting business. He stepped in to help his mother after his father died in 2003. His parents had been married for 54 years.

At first, Woodward did all the repairs at his mother’s home on Tucson’s north side, and as the years passed and she could no longer drive, he helped with grocery shopping, paying her bills and driving her to medical appointments and church. He visited often, leaving work when he needed to attend to her affairs.

He remained in Tucson, turning down a job offer in California because his mother needed him. She suffered from anxiety and dementia. He nursed her through falls, and he wanted her safe so she moved to an assisted-living facility in August 2017.

He visited her every other day, and because of her failing health she was placed in hospice care. Dorothy Woodward died in December at age 92.

“I got through because of my faith, my family and my church. I did the right thing. I honored my mother,” he said in reflection.

For Nickie Norris-Durik, her life was uprooted in 2001 when her father became ill and her mother needed help.

She worked as a computer programmer, and her husband was a supervisor at a recycling plant in Florida. They sold their home and moved to Tucson with their 8-year-old daughter.

Nickie gave support to her mother, who tended to her father, a retired Air Force veteran. He suffered a fall, which resulted in a brain injury. He died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2012 while in hospice at the VA hospital. The couple was married for 62 years.

Nickie and her sister helped care for their mother, who remained in her home but became depressed after the death of her husband. She stopped driving at age 80, and Nickie was doing her shopping and took over her finances. She eventually sold her mother’s home and paid off her debts.

In January 2017, Nickie moved her mother into her east-side home. She was diagnosed with dementia and had trouble walking. She fell earlier this summer and suffered a lower-back fracture.

“It was too much for her,” said Norris-Durik of the trauma. Her mother, Evelyn Jane Norris, died in June at age 84.

“The most difficult was seeing her decline. Sometimes she didn’t know who I was,” said Nickie. “When she was lucid, she would apologize for being a burden. But I told her she wasn’t a burden. I was doing for her what she did for me when I was a child.”