Early in Jose Antonio Vargas’ book, he writes about a life-altering day when he pedaled on his mountain bike to the office of the Department of Motor Vehicles.

“I was 16, the age when American teenagers were supposed to get their licenses,” he writes in “Dear America.”

For identification, he took his high school I.D. card and, since he was a Filipino immigrant, his green card. But after examining the green card, the clerk abruptly told him it was fake. Vargas was sure the clerk was wrong and he returned home to ask his grandfather, Lolo, about the card.

“Without addressing the question, he got up, swiped the card from my hand and uttered a sentence that changed the course of my life,” Vargas writes.

His grandfather said to him in his native Tagalog: “Don’t show it (the card) to people. You are not supposed to be here.”

Dear reader, stop here for a moment. Let what Lolo told his grandson sink in.

He is not supposed to be here. He doesn’t belong. He is an outlier.

Author Jose Antonio Vargas, at 23, with his grandfather, Lolo. When Vargas was 16, his grandfather revealed to Vargas that he had a fake green card and was undocumented.

It pained Lolo to tell his grandson that his card was fake and that Jose, who had migrated to California when he was 12, did not have legal papers. It devastated Vargas, who is now 37.

And for millions of other Americans like Vargas, the revelation of their true legal status has been devastating as well. It has placed limitations on their ability to work, to travel, to become fully integrated citizens in a country they call home. And for many of the millions, this country is the only country they know.

Jose Antonio Vargas emerged as one of this country’s most visible “undocumented” Americans in 2011 when he penned his essay, “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” in the New York Times Magazine.

A former newspaper reporter with the Washington Post, Vargas emerged as one of this country’s most visible “undocumented” Americans in 2011 when he penned his essay, “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” in The New York Times Magazine.

Since then, Vargas, a journalist and documentary filmmaker, has traversed the country speaking truth to power about an immigration system that destroys families and about Americans living here without legal authorization. And as he has related his own story, Vargas has heard many other stories of hardship, courage and faith.

“The honest but the most rewarding experience is learning their stories, how heavy they are to carry,” Vargas said in a recent phone interview as he drove from Oakland to Menlo Park, California, where he grew up with his maternal grandparents and other family members.

Vargas will participate on four panels at this year’s Tucson Festival of Books, March 2-3 at the University of Arizona. The author of “Dear America, Notes of an Undocumented Citizen,” writes about his experience and the shared burden of psychological weight that undocumented Americans carry with them as they navigate their lives.

Jose Antonio Vargas’ book was published last year. He will be participate on four panels at the Tucson Festival of Books at the University of Arizona, March 2-3.

He listens as they divulge secrets, their fears and uncertainties. “The border is the language they have to talk about themselves — in apolitical ways,” said Vargas.

Since its birth, this country has consistently told others that they do not belong here. This country has continuously defined, in different ways, who is allowed to be in this country and who is not. Who is American and who is not, have been the perpetual questions.Still, Vargas said, “This country can’t have an honest discussion about immigration.”

Most discussions, however, are one-sided. They are dominated by powerful political (President Trump) forces and other xenophobic forces (Fox News Channel) that from the get-go demonize undocumented Americans and insist that any conversation about them must begin with their expulsion. Additionally, the discussions are largely devoid of active participation by undocumented Americans.

“We have to remind people that we’re talking about someone else’s father, son, daughter,” said Vargas, who has not seen his mother and younger sister since he boarded a plane in Manila bound for the United States. And he has yet to meet his younger brother.

Jose Antonio Vargas and his mother in the Philippines.

These are real people. Undocumented Americans are not faceless, nameless caricatures or rapacious criminals lurking around the corner.

So let’s talk about the undocumented mothers and fathers in our midst who are raising their American children; the undocumented workers who sustain our economy and pay taxes and contribute to the depleting Social Security fund knowing that they cannot draw from it; the undocumented college students who will become educators, physicians, attorneys, civil-rights activists, social workers; the undocumented residents who fear the next time they come into contact with local police and are forced to prove their legal status.

Vargas’ book, while a short 232 pages, goes a long way in revealing the struggles of an undocumented American, having to lie to exist, living while looking over a shoulder for immigration agents.

And what the book also reveals is that living in this country as an undocumented American means that you belong here.

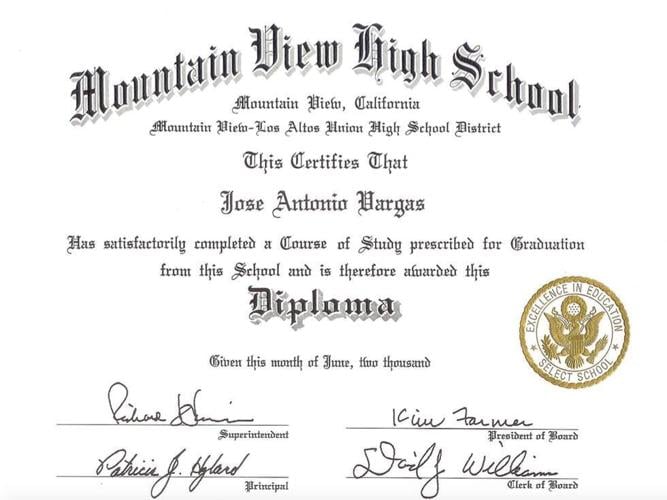

Jose Antonio Vargas’ high school diploma.