James S. “Big Jim” Griffith lived such a big life defining Tucson’s senses of place and self that it’s hard to imagine this special place without him, as many admirers have been saying since his death Saturday at age 86.

He was a folklorist, cultural anthropologist, storyteller extraordinaire, banjo picker, University of Arizona scholar of religious art, artifacts and practices, co-founder of the Tucson Meet Yourself festival, lover of Tohono O’odham waila music and kwalya dance, historical preservationist board member of Patronato San Xavier, a 6-foot-7-inch-tall cowboy poet, an author, an encyclopedia of wit and wisdom.

Other descriptions keep coming to mind as well, often in Spanish, for those who knew him best.

“He was the best compañero that one could have — simply the best companion for the journey, any journey, anytime,” said Father Greg Adolf, who often traveled with Griffith, his friend of 45 years, on Kino mission tours to Sonora.

“He was one of the best connectors of people, across any divide, wall, chasm,” Adolf said in an emotional interview Sunday. “We always said ‘build bridges, not walls.’ He was a founder, who built foundations so others could build on them.”

Peter Yucupicio said Griffith was “what we say in our villages, un hombre de su palabra, a person of his word. His word meant something to all of us.”

Yucupicio is chairman of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe but describes himself as “more than that, Jim’s good friend. I am 64 now, but going back to my teens and 20s, he would come to our villages, our communities, and everyone would greet him — ‘There’s Jim right there.’ He became a member of our community, of our Yaqui life and traditions.”

“There’s only one Big Jim,” he said. “And the thing he did was to bring awareness of all the different types of ethnicities and races living here, and the beauty of bringing us all together.”

“He had that big heart to all people,” said Gertrude Lopez, a waila accordionist and, as leader of Gertie N the T.O. Boyz, “the only female band leader on my reservation.”

“I am very thankful for having him in my life and knowing all he did for Native peoples, but also for all of Tucson,” said Lopez, recalling that Griffith came to many of her gigs.

“I thank the Lord for him,” she said. “Lot of blessings to him and his family and to the whole Tucson family.”

All welcome

Griffith, who was born in Southern California in 1935, moved to Tucson in the 1950s for undergraduate studies in anthropology at the University of Arizona, and went on to get his Ph.D. there, as well, says his daughter, Kelly.

Anthropologist and folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith plays banjo on the front porch of his home on Mission Road southwest of Tucson in 1974.

He died “very peacefully” at his home in Tucson on Saturday, Dec. 18, after several years of health problems, she said.

“He had a good 86-year run. He really did,” noted Loma, Jim’s wife of nearly 60 years. She met him in Santa Barbara, California, before he moved to Tucson, and later moved here to marry him, Kelly says.

As friend after friend points out, Loma is an inseparable part of his legacy.

Their gracious hospitality, always at the ready, is at the heart of many joyous scenes and anecdotes being remembered.

“He always told me, ‘You just stop by anytime you want. It’s an open-door policy,'” said Martín DeSoto, who was on the Patronato board with Jim and is a docent of San Xavier Mission.

“I would come by, and we would talk about santos, books, his travels — and, on an inch ruler, we probably only got to about an eighth of an inch of his knowledge on any subject, because he knew so much. It’s our history — the O’odham, the Yaqui, everyone. And Loma would always say, ‘Take whatever books you want.’”

DeSoto didn’t have far to go to bask in that friendship. The Griffiths lived just outside the boundary of the San Xavier District of the Tohono O’odham Nation, close to the mission. Jim moved out there in about 1955, “when I was about 2 years old,” DeSoto said, because he loved the historic church so much and wanted to live among the O’odham.

DeSoto had been born very nearby on his grandparents’ and parents’ ranch and still lives in that area. He recalls that another renowned Southwestern historian and anthropologist, the late Bernard “Bunny” Fontana, also had a home nearby.

Jim was playing banjo and was part of “the music ministry” when DeSoto first met him at a Saturday night mass at the mission in about 1992.

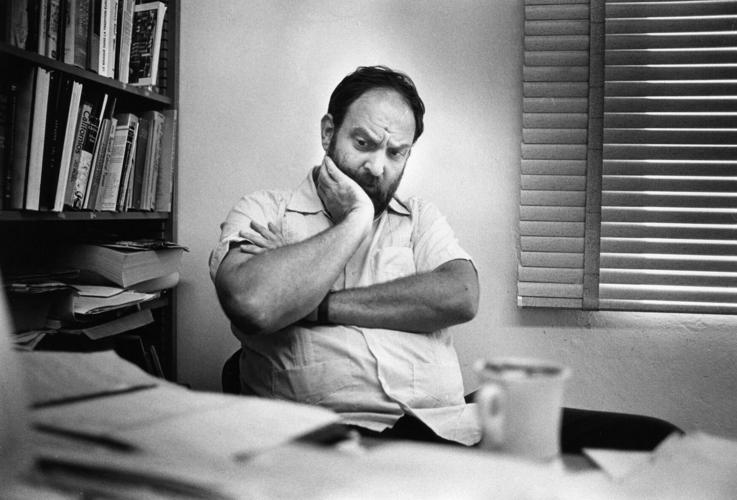

Anthropologist and folklorist James S. "Big Jim" Griffith in his office in 1982.

Like many others, DeSoto tells of Jim and Loma’s memorable parties.

“His summer birthday parties, in August, are imprinted on my children’s minds,” said Joseph Wilder, retired director of the Southwest Center. “It was just fabulous to see all the desert rats who showed up — (archaeologist) Julian Hayden, Bunny Fontana, (author) Chuck Bowden. It was part of my children’s formation, and weren’t they lucky, to see this desert life that was informed by the place and the languages spoken here.

“Jim would have someone barbecuing carne asada, and there would be a trio of mariachis. … He was simply an icon of Tucson, and I looked up to him, literally and figuratively.”

The food wasn’t just delicious, it was a chance for Griffith to say, with a trademark little smile on his face, that “every time you have carne asada or a quesadilla, you are celebrating Padre Kino,” as Father Adolf noted.

As an expert on Eusebio Francisco Kino, who founded the San Xavier Mission, and churches in what is now Sonora, Griffith loved to point out the many foods the 17th century Jesuit missionary explorer introduced to the borderlands.

One borderland, undivided

Griffith also worked for decades to celebrate and promote the Sonoran Desert borderlands as a cohesive region, the Pimería Alta of Northern Sonora and Southern Arizona, “our own cultural treasure house of food, song, common expressions. We live in the borderlands, everything from Tucson to Hermosillo,” Adolf said.

Adolf believes Griffith recognized Kino as a fellow “bridge builder, transcending his culture and bringing together cultures. I think they were kindred spirits.”

Jim Griffith, left, and Greg Morton play during a meeting of the Cultural Exchange Council of Tucson in 2005.

They both had “a great gift of asking others what they know, for their valuable, priceless information about desert living,” he said. The spirit of hospitality, of all being welcome, was returned to both in turn, Adolf added.

Griffith was always a learner and a friend, not just a teacher, said Maribel Alvarez, who holds the Jim Griffith Endowed Chair for Public Folklore at the UA.

She believes that’s one reason Indigenous communities “feel very close to him and have a tremendous, abiding love for Jim,” Alvarez said. Sometimes, she said, the relationship between Indigenous people and anthropologists can be contentious, as in, “here comes the outsider to say how ‘these people’ live.”

His No. 1 value “was respect,” she said. “He was deeply curious about people, and he knew the one thing that can breach tough conversations is to enter with respect and not with preset ideas.”

Yucupicio agrees.

“He would always sit there and learn. I would go with him on trips to Sonora, and it was always an honor to talk about Yaqui history. He would say, ‘You have been around here for thousands and thousands of years.’ ‘Yes we have,’ I would say. Driving with him was always a learning time for me and for him.”

Alvarez is also the program director for Tucson Meet Yourself, the festival Griffith co-founded in 1974, drawing about 2,000 people the first year. In 2019, before the pandemic, it brought 150,000 to downtown to enjoy food, music and dances of “the richness of cultural traditions and practices” we have here, from Chinese, to Polish, to Yaqui, to Filipino and scores more.

“He held it all together as the emcee,” Alvarez noted. “He taught us about culture as a living, dynamic way of connecting through relationships and respect.”

“He helped Tucson to understand itself,” said prominent local author Gregory McNamee. “He taught us about who we, as Tucsonans, are.”

As DeSoto put it, “We’re all one people, one body. He didn’t like any division.”

In addition to wife Loma and daughter Kelly, Griffith is survived by a son, David, and two grandchildren.

A celebration of his life will likely be held in the new year.

Photos: Tucson folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith

Jim Griffith, 1984

Updated

"Big Jim" Griffith, center, joins with Dean Armstrong and the Arizona Dance Hands at a fiddlers contest at Armory Park, Tucson, on Feb. 27, 1984.

Jim Griffith, 1974

Updated

Anthropologist and folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith plays banjo on the front porch of his home on Mission Road southwest of Tucson in 1974.

Jim Griffith, 1982

Updated

Anthropologist and folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith in his office in 1982.

Jim Griffith, 1984

Updated

Jim Griffith directs volunteers during a preparation meeting for the annual "Tucson Meet Yourself" in 1984. Griffith was a key founder of the event.

Jim Griffith, 1984

Updated

Jim Griffith directs volunteers during a preparation meeting for the annual "Tucson Meet Yourself" in 1984. Griffith was a key founder of the event.

Folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith, Tucson

Updated

Folklorist Jim Griffith in front of San Xavier Mission del Bac Mission in 2011, the year he was honored by the National Endowment for teh Arts.

Folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith, Tucson

Updated

Jim Griffith, left, and Greg Morton play during a meeting of the Cultural Exchange Council of Tucson in 2005.

Folklorist "Big Jim" Griffith, Tucson

Updated

Jim Griffith at his home in 2019, after publication of his new book, "Saints, Statues and Stories. A Folklorists looks at the Religious Art of Sonora."