A woman changes a baby’s diaper amid a trash-strewn cell floor while being detained by the Border Patrol in Douglas.

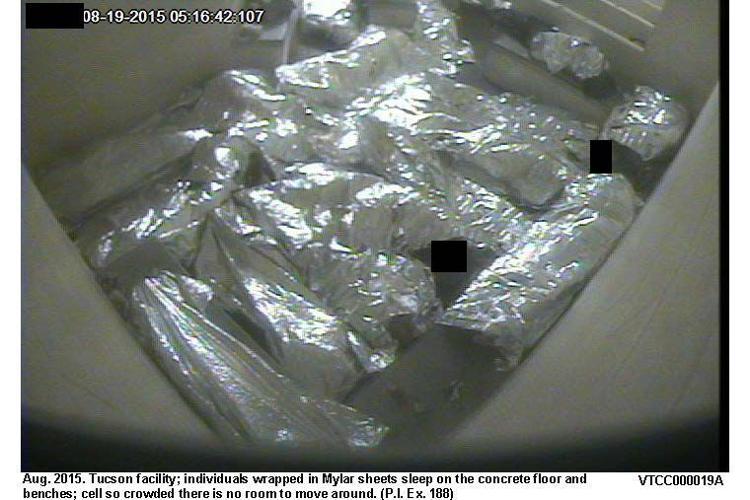

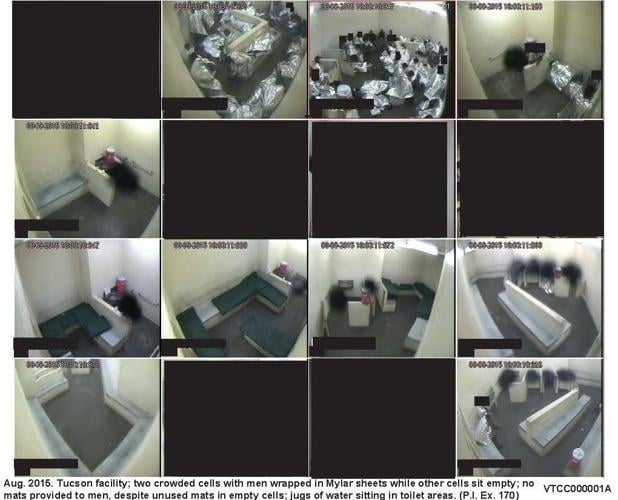

Some detainees lie on floors while sleeping mats are stacked in nearby empty cells in a Tucson facility, others wrap themselves head to toe in blankets that look like aluminum foil as they are crowded so tightly in a cell there is virtually no space to move around.

Those images and a dozen others taken by Border Patrol cameras and made public Thursday morning in a federal court case show what advocates call “overcrowded and filthy” Tucson Sector detention centers used to house illegal immigrants.

The lawsuit was filed June 8, 2015, in U.S. District Court in Tucson on behalf of three detainees, two of whom are seeking asylum, and others who were confined to cells that are kept at such low temperatures they are known as “hieleras,” or iceboxes.

The lawsuit was filed by the Morrison and Foerster law firm, National Immigration Law Center, American Immigration Council, the ACLU Foundation of Arizona, and the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area.

They allege more than 75 former detainees in 2014 and 2015 reported similar conditions in Tucson Sector holding cells, where Border Patrol guidelines say detainees should spend no more than 12 hours.

Despite those guidelines, agency records obtained by the plaintiffs showed 80 percent of the 72,198 people detained in the Tucson Sector in the first half of 2013 were in custody for more than 24 hours. One-third were held for more than 48 hours and 11 percent for more than 72 hours.

The plaintiffs claim the Border Patrol violates its own policies and the detainees’ constitutional rights to due process by depriving them of sleep, sanitary conditions, medical screening and care, adequate food and water, and warmth.

The agency also deprives detainees of regular contact with the outside world, the lawsuit alleged.

“The deliberately punitive, harsh conditions and severe restrictions on outside communication also serve to facilitate the coercive practices for which the agency is notorious,” the lawsuit stated.

The plaintiffs asked the court to issue an injunction barring the Border Patrol from depriving detainees of their constitutional rights. They asked the court to order the agency to provide beds, hygiene products, clean water and food, avoid overcrowding cells, and provide medical care, as well as award the plaintiffs their costs.

Experts and photographers were able to visit several detention centers in Arizona after hearing “countless accounts” of poor conditions, said Nora Preciado of the National Immigration Law Center. Previously, those accounts were dismissed as anecdotal, she said. The newly unsealed evidence “allows the public to see for themselves,” she said.

Photos and court documents filed by the plaintiffs describe the conditions experts said they witnessed during tours of the detention facilities or saw in surveillance video. (Read the court documents online with this story.)

Eldon Vail, a retired corrections administrator with 35 years of experience working in adult and juvenile facilities, said the conditions at the detention centers would be “unthinkable” in any other jurisdiction.

The Tucson station was so cramped, some detainees lay down on concrete floors beneath toilet stalls. Others were “crammed so tightly, they look like sardines in a can,” he wrote.

Some toilets didn’t flush, while many were “leaking and stained with built up grime from overuse” and “diapers, toilet paper and other trash were strewn around the bathroom area,” Vail wrote.

During his inspection of the Casa Grande station, there were only three sleeping mats in the entire facility, he wrote. At other stations, detainees slept on the concrete floor “while, at the exact same moment in time in the same station, mats go unused in other unoccupied or less occupied cells.”

The lights in the cells are kept on day and night, and agents interrupt detainees’ sleep in the middle of the night to conduct cell counts or call individuals in or out of the cells.

Video showed 5-gallon water coolers often placed on toilet stalls or the ground with few or no paper cups, despite cups being stored at the stations, Vail wrote.

At the Casa Grande station, a 1-gallon water jug was used by a dozen detainees over the course of five days without being cleaned, he wrote.

In cells with 15 or more detainees, they must share four or five paper cups or drink directly from the cooler.

In terms of food, the stations served microwaveable burritos, crackers and boxes of fruit juice, Vail wrote. The stations also had baby food and formula, but nothing specifically for children or pregnant women.

The food is usually served at seven- or eight-hour intervals and detainees reported agents threatening to confiscate the food to keep detainees quiet, Vail wrote.

Agents removed detainees’ outer clothing, leaving some wearing short-sleeve shirts and having to use mylar blankets to keep warm as temperatures in the cells dropped to 58 degrees.

A Mexican woman reported asking an agent to turn off the air conditioner, but the agent said, “Don’t ask or we’ll turn it up,” Vail wrote. Children cried from the cold, and one detainee said he understood why “dogs sleep in a little ball, to keep warm but couldn’t even keep warm doing that.”

Officials told Vail the showers were used only when a detainee showed evidence of scabies. Out of nearly 17,000 detainees held between June 2015 and September 2015, the plaintiffs’ review of video surveillance showed only 115 showers.

The declaration on behalf of the Border Patrol by Richard Bryce, a 33-year veteran of law enforcement who has inspected more than 120 jails and prisons, painted a drastically different portrait of the detention facilities.

After inspecting stations in Douglas, Nogales and Casa Grande in January, Bryce said the detention centers “bore no resemblance” to the facilities described by the plaintiffs.

The facilities were “professionally run, adequately maintained and meet their intended purpose of short-term detention during immigration processing,” Bryce wrote.

Mexican consular officials are regularly available to hear complaints from detainees, the food and water are clean and readily available, and agents act professionally in handling the irregular flows of detainees, Bryce wrote.

Following the release of the images, the Border Patrol issued a statement saying its parent agency, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, is “charged with enforcing the nation’s laws while protecting the civil rights, civil liberties and well-being of every individual with whom we interact.”

The agency is “committed to the safety, security and welfare of those in our custody, especially those who are most vulnerable.”

“CBP works to ensure proper conditions and treatment of detainees in all of our holding facilities and is subject to unannounced inspections by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General of these facilities.”

The detention facilities are “designed to be short-term in nature to hold individuals until they can be processed and turned over to another agency or repatriated,” the agency said.

In March, the Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General announced it would inspect facilities run by CBP and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in response to complaints.