A federal judge in Tucson indicated Tuesday he would direct the Border Patrol to improve sleeping conditions at the agency’s detention centers in Arizona, calling the current situation faced by detainees a violation of their civil rights.

U.S. District Judge David C. Bury said he planned to tell the Border Patrol to avoid depriving detainees of sleep while a lawsuit filed on behalf of three former detainees unfolds. The civil trial — which also deals with claims of poor food, frigid temperatures and lack of access to medical care — is to begin next summer.

“I think the deprivation of sleep, at the very least, in this case is a violation of the civil rights of a civil detainee and that needs to be fixed,” Bury said at a hearing Tuesday.

Although Bury did not issue a formal order, he said he planned to consult with lawyers representing the Border Patrol and the Morrison and Foerster law firm that filed the lawsuit along with several immigrant-rights groups in the coming days so they can work out a solution.

He acknowledged that “the Border Patrol has a really tough job,” but in his closing remarks said, “The complexity of government operations cannot trump civil rights. Neither can budgetary constraints.”

Bury said he had not heard enough testimony from expert witnesses about the food, temperature and medical claims to make a decision on those points.

Border Patrol officials argued that an order to improve detainees’ sleeping conditions would complicate the functioning of Border Patrol stations and could lead to detainees spending more time in detention.

The stations operate 24 hours a day, and agents are constantly processing recently arrived detainees, which often interrupts the sleep of the detainees already at the stations, said George Allen, assistant chief patrol agent for the Tucson Sector.

In order to set aside time for detainees to sleep, agents would have to stop processing new arrivals. That would lead to a bottleneck at night, which is when most apprehensions occur, and further delay the processing of all of the detainees, Allen said.

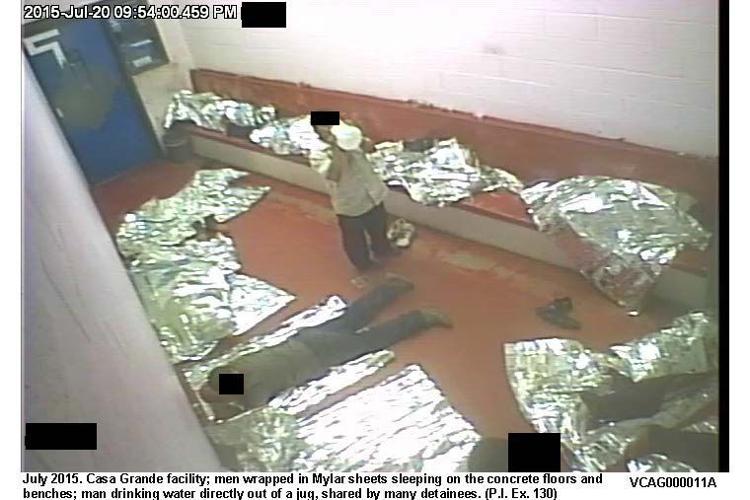

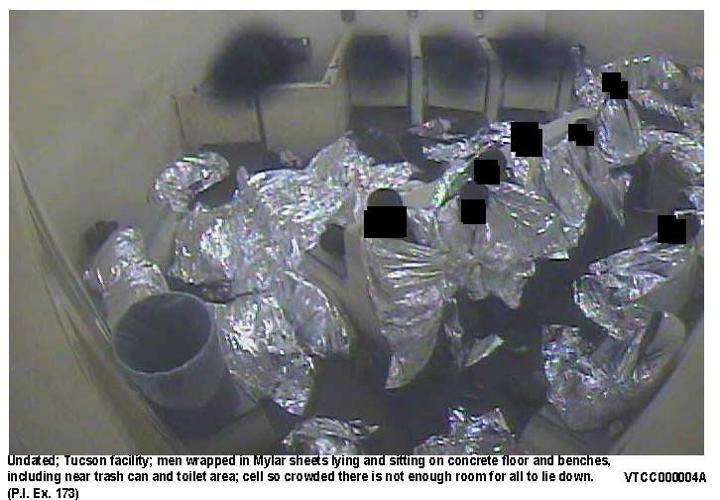

Agents provide every detainee with a mylar survival blanket to trap their body heat while they sleep, Allen said. The agency tried providing cloth blankets years ago, but the laundry demand was too much for any local company.

Every child is provided with a sleeping mat, as are most women with small children, Allen said. The agency could provide sleeping mats to all detainees, but the holding rooms do not have enough floor space for the mats.

With regard to temperature, Allen said the thermostat at Border Patrol stations in Arizona is either computer-controlled at about 73 degrees or monitored every shift by agents.

In August, the plaintiffs released still photos taken from Border Patrol cameras that showed detainees lying on concrete floors while sleeping mats were stacked in nearby cells at the Tucson detention center.

Other photos showed detainees wrapped from head to toe in mylar survival blankets in a room so crowded there was virtually no space to move around.

Agency records obtained by the plaintiffs showed 80 percent of the 72,198 people detained in the Tucson Sector in the first half of 2013 were in custody for more than 24 hours. One-third were held for more than 48 hours and 11 percent for more than 72 hours.

The eight detention centers in Arizona were designed to hold people after their arrest for crossing the border illegally and before their transfer to another agency, such as the U.S. Marshal’s Service.

The plaintiffs pointed to a 2008 Border Patrol policy that said detainees should not be held longer than 12 hours.

Justin Bristow, acting chief for strategic planning and analysis at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., testified that the policy was a guideline that should be followed whenever possible, rather than an “absolute requirement.”

Bristow said some of the hours listed as in custody typically would be spent waiting in the desert for transport to the nearest station, which could take several hours of travel.

The speedy processing of detainees is further complicated by demographic changes, he said.

In 2008, most of the people held at the detention centers were Mexican adults who could be repatriated at the U.S.-Mexico border, Bristow said.

However, the number of detainees from other countries, particularly from Central America, has risen dramatically in recent years, as has the number of unaccompanied minors, he said.

As a result, agents have to do more in-depth interviews and arrange complicated logistics with other agencies, which takes more time, Bristow said.

Bury questioned Allen about the more comfortable conditions inside the Santa Cruz County jail, which houses undocumented immigrant detainees on behalf of the U.S. Marshal’s Service.

“Don’t you think it’s time that your facilities are modified or changed to accommodate the human need at least for sleep if you’re going to keep somebody for two or three days?” Bury asked.

Allen responded that other agencies, such as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, have space at their facilities that could help the Border Patrol.