PHOENIX — State lawmakers are being asked to enact Arizona’s first rules on when police can use technology to track cellphones.

The legislation crafted by the Attorney General’s Office would make it clear in law that state and local police are required to get a search warrant before using devices such as a “StingRay,” which can home in on individual cell phones, said spokeswoman Mia Garcia.

“The proposed legislation would put Arizona at the forefront of protecting individual privacy while simultaneously helping police keep our community safe,” Garcia said.

Will Gaona, an attorney with the Arizona chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, called SB 1342 “a step in the right direction to increase police transparency and protect Arizonans’ privacy.” But Gaona said it does not go gar enough given the capabilities of the technology.

The ACLU knows something about that technology.

It fought a multi-year lawsuit against the city of Tucson to try to uncover not only how the StingRay device works, but its capability to track not just the targeted suspect but anyone else nearby.

That legal battle ended with the state Court of Appeals concluding that Tucson and other cities with the cell-tracking technology need not tell the public how it works. The judges said such information could help criminals evade the law.

A lot is known, nonetheless, about the devices and how they take advantage of cellphone technology to pinpoint a specific device.

Put simply, what enables a cellphone to work is that it sends out an electronic signal searching for the nearest tower. The phone then essentially “logs in” to that tower.

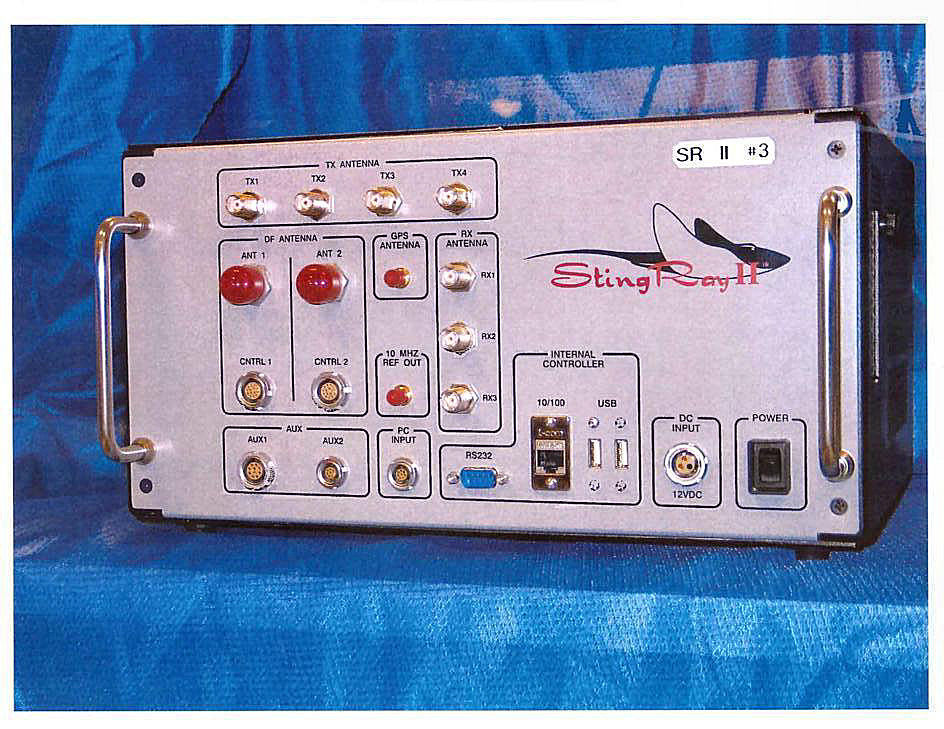

Devices like the StingRay, manufactured by the Harris Corp., trick cell phones into thinking they are towers, so the phone logs into them.

That allows police, armed with information about the specific phone, to track it. And since the devices are portable, police can take them door to door to find the person they want.

But because these devices mimic cellphone towers, they also can trick other phones in the area to also log in — phones that may belong to people who have nothing to do with the incident police are investigating.

In rejecting the ACLU bid for operating information, the Court of Appeals left unknown exactly what happens to all that other information. Gaona said that needs to be addressed in the proposed legislation.

“A provision should be added that would require the prompt deletion of bystander data,” he said.

Garcia countered, “Typically in those search warrants the judge will say (that) any other (cell) numbers must be deleted within this (tracking) time frame,” she said. But she said there’s no reason to put such specifics into state law.

“That’s something that we want the judge to have a little bit of discretion over,” Garcia said.

Gaona said it’s good that police will be required to get a warrant from a judge. Information developed in the lawsuit the ACLU filed against Tucson resulted in a statement from Lt. Kevin Hall that his department used the device at least five times but had not sought or obtained a warrant in any of those cases.

The requirement for a warrant, by itself, may be insufficient protection, Gaona said. He said judges may not be as familiar with tracking technology as they might be with a wiretap on a specific phone or a “pen register” that logs phone calls on a particular line.

“Law enforcement should also be required to disclose the cell site simulator’s capabilities to the judge who is being asked to sign the warrant,” Gaona said.

He also wants the public to be told exactly what kinds of electronic monitoring police are doing .

Garcia said the devices are an important tool for police and can be used to find people involved in such crimes as drug trafficking, terrorism and child abduction.

As written, the legislation requires police to provide “probable cause” to a judge naming the person or phone to be tracked. But the proposal lists multiple reasons a warrant can be issued.

For example, tracking would be permitted if the phone was used, is being used “or is about to be used as a means of committing a public offense.” Warrants also could be issued to track individuals if police can show the phone is in the possession of someone who has committed or is about to commit a crime.

Warrants also would be permitted if the phone itself constitutes evidence that an offense has been or will be committed.

Warrants are good for up to 60 days, though multiple extensions are possible.

The legislation does require that police or prosecutors notify the person who owns the phone being tracked within 10 days after the tracking ends. Police could ask judges to delay notification, if necessary, for a variety of reasons.