PHOENIX — Tucson and other cities with cellphone-tracking technology need not tell the public how it works because it also could help criminals evade the law, the state Court of Appeals has ruled.

In a unanimous decision, the judges rejected arguments by the American Civil Liberties Union that the public has a right to the information. They said that it would not be in the “best interests of the state.”

The ruling involves efforts by a freelance reporter being represented by the ACLU to expose not only the workings of a device owned by the Tucson Police Department but how it also can identify cellphones of others who are not suspects in criminal cases. Freelance writer Beau Hodai said the documents also would show whether police are getting search warrants before tracking someone or simply doing so on their own.

And while the decision specifically addresses the battle to get records from Tucson police, it sets legal precedent for those who would seek the same information from other agencies around the state.

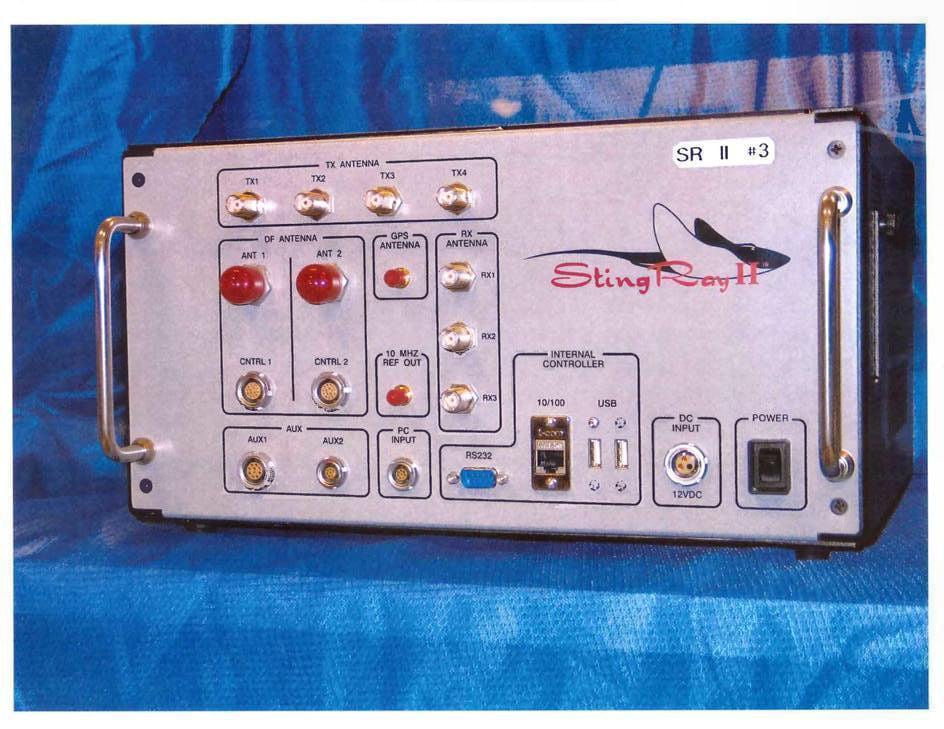

At the center of the fight is a device called a Stingray. What’s already known is that it takes advantage of the way cellphones work: When a phone is within range of a cell tower, it essentially “logs in” to that tower. That ensures that the owner not only can connect to make calls but that the system finds that specific phone when someone is trying to call the owner.

In essence, the Stringray mimics a cellphone tower, logging in to it the same as it would for a regular tower.

That enables police, armed with information about the specific phone, to track it. And since the Stingray is portable, police can take it door to door to find the person they want.

Hodai said that raises questions about the information that might be gathered on those who are not targets. And he said the materials about how police can use it could show whether agencies are being candid with courts over the capabilities of the technology.

When the case finally went to the Court of Appeals, attorneys for the city said they were no longer using the device, though they have not gotten rid of it.

But they cited an affidavit from an FBI special agent who said that providing information about cell site simulators would provide “adversaries” with “information necessary to develop defensive technology, modify their behaviors, and otherwise take countermeasures designed to thwart the use of the technology.”

Appellate Judge Michael Miller, writing for the unanimous three-judge panel, said the ACLU never provided any evidence to contradict the affidavit. Miller said that means he and his colleagues have to accept it as true.

That logic frustrated Pochoda.

He pointed out that he never had access to the materials the city seeks to shield, meaning there was no way he could argue that its release would not harm the public interest. And Pochoda said the trial court never provided an opportunity to present any evidence to contradict the FBI’s claims.

“It’s a Catch-22,” he said.

Pochoda also argued that the concerns of the FBI, even if true, do not allow the Tucson Police Department to shield the information.

“There’s a real question whether that’s relevant to Arizona’s Public Records Law,” he said. And Pochoda said if Tucson isn’t using the device, then the city cannot claim information about how it operates harms the Police Department.

But Miller, in the ruling, cited case law that says state law is not as narrow as Pochoda claims.

“The ‘best interests of the state’ standard is not confined to the narrowest interest of either the official who holds the records or the agency he or she serves,” the judge wrote. “It includes the overall interests of the government and the people.”

The ruling was not a total loss for the ACLU.

Miller noted that a PowerPoint presentation that was withheld has more than technical information about the equipment.

“It also provides guidance to law enforcement about how use of the equipment fits within the broader context of the rules of criminal procedure, such as obtaining search warrants,” the judge wrote. And he said there is no reason that cannot be made public.

In December, Tucson police said it no longer used the devices.

It noted then that they were used in five police investigations since 2010. The city paid $408,000 in federal grant money to Florida-based Harris Corp. for a vehicle-mounted device and a backpack-sized device. That amounts to $81,600 per investigation.