The United States is the world’s leading crude gypsum producer with an estimated production of 20 million tons per year.

Gypsum is a common mineral and one widespread across Arizona.

However, production is limited in contrast to major producing states including Iowa, Kansas, Nevada, Oklahoma and Texas.

Created by the evaporation of water from inland seas and salt lakes, gypsum, a hydrous calcium sulfate, is often found in deposits containing impurities such as calcium carbonate, clay, iron oxide, and silica. Characteristics include fine-grained, massive, and crystallized with coloration ranging from white, translucent, or gray with red, yellow or brown hues. Gypsite contains gypsum crystals, clay and silt. Four crystalline varieties comprise gypsum including selenite, satin spar, desert rose and gypsum flower.

Along with limestone, clay and shale deposits, gypsum is one of the principal materials often used in the manufacturing of Portland cement. Commercial production of gypsum in Arizona has existed since 1880. The western foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains are noted among the earliest recorded production of gypsum during Arizona’s territorial days. This gypsum was used for plaster in the construction of the St. Augustine Cathedral in Tucson.

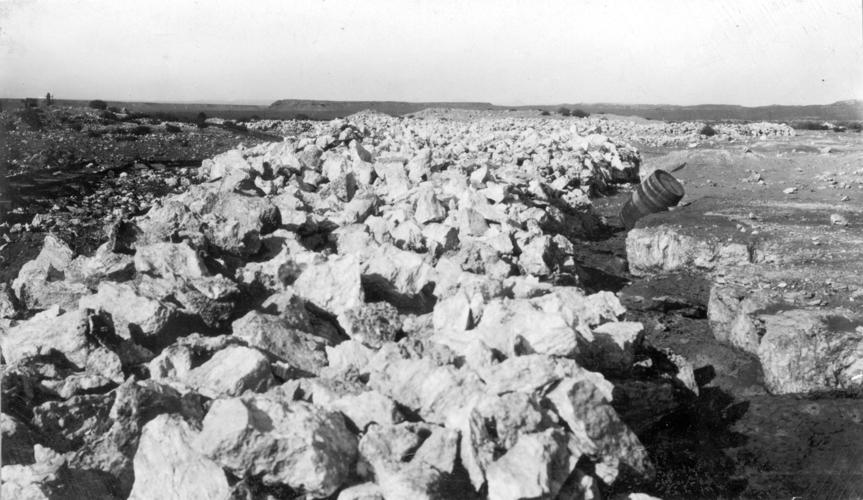

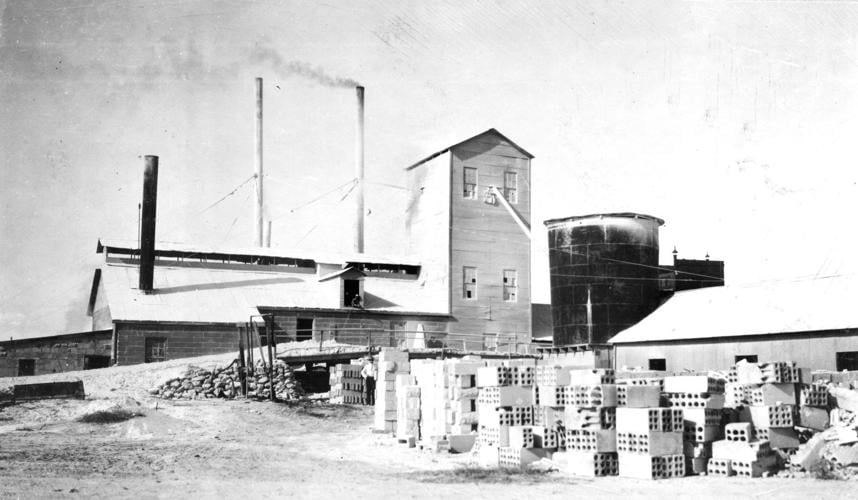

Douglas was another prominent locality for mining gypsum from 1908 to 1932. Intermittent operations by the Arizona Gypsum Plaster Co. focused on surface deposits east of the smelter town consisting of up to 6-foot thick irregular lens-shaped bodies of light buff to white gypsum.

The gypsum was calcined, a necessary step for plaster production.

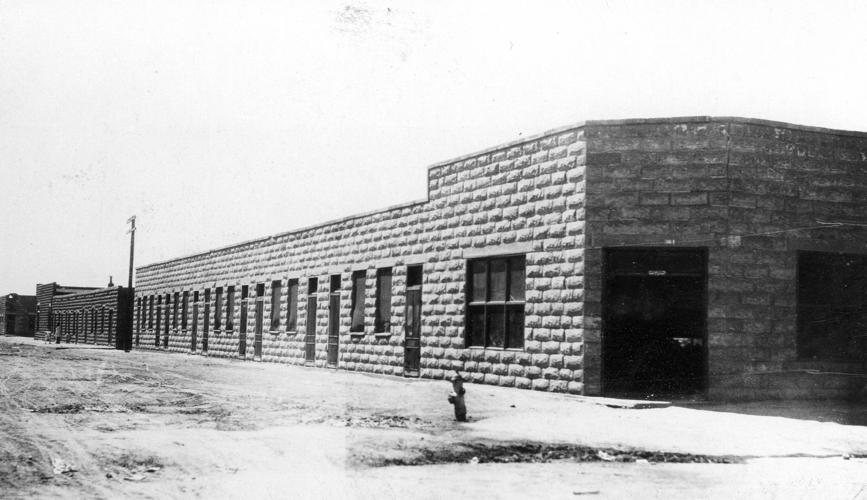

Gypsum blocks were also manufactured for local commercial and residential buildings.

"We're tough as saguaros," editorial cartoonist David Fitzsimmons says. He says he saw a video made for the people of Detroit and became inspired to do his own take for Tucson.

From 1909 to 1914, gypsum was quarried as large plates of selenite at several localities near Winslow in Navajo County. Mined by the Acme Cement Plaster Co. and Navajo Gypsum and Fertilizer Co., the product was shipped to Riverside, California, for use as a retarder at a local cement plant. The long abandoned Mormon settlement of Zeniff in the Holbrook Basin near a dry lake was primarily a dry farming and cattle community during the first half of the 20th century.

However, the surrounding area does contain halite and anhydrite deposits most notably mined at the Snowflake quarry 10 miles east during the early 1900s.

Gypsum and anhydrite are noted for their agricultural applications. These include soil additives to aid in crop growth wherein gypsum is known as “land plaster” containing the ingredients of sulfur and calcium. This is especially helpful in Arizona wherein it is used to reduce black alkali or excessive sodium in soils caused by irrigation waters. Land plaster is also used in stucco production when processed by kettle or flash calciners wherein three-quarters of chemically bound water is removed. Anhydrite is a select additive to peanut crops. Uncalcined or non-heated gypsum acts as a retarder when up to 6% by weight of gypsum is mixed with cement clinker added to the setting time for Portland cement.

Anhydrite, an evaporate mineral that occurs with gypsum, halite and limestone, is derived from the Greek term “anhydrous,” meaning lacking water.

While considered less common than gypsum, it transforms to gypsum when exposed to humidity or mixed with ground water. Gypsum can be modified to anhydrite by the application of heat/calcined at 900 degrees F.

Christened “dead-burned gypsum,” it is used as a desiccant in the manufacture of Keene’s cement, a hard-finish plaster used in skirtings, scrubbable walls and floor surfaces.

By the 1950s, gypsum became a necessary mineral commodity for the development of the Arizona economy due to its usage as an ingredient in cement for construction and agricultural needs including wallboard, glass manufacture and soil conditioning. Studies have shown that uncalcined gypsum has proven to treat alkali soils as fertilizers helping improve yields of clover and cotton production. Sulfate in gypsum provides sulfur to plants for protein photosynthesis.

Prominent gypsum mines at the time included properties near Feldman and Camp Verde operated by the Arizona Gypsum Corp. The latter supplied gypsum products to the Clarkdale cement plant. Winkelman also contained an open pit gypsum mining operation. Gypsum deposits have also been found at such porphyry copper deposits such as Mission Copper deposit and Copper Cities near Globe-Miami. Other noted areas containing gypsum and anhydrite beds include the Willcox, Hualapai Valley and Supai Basin vicinities. However, at depths in excess of several hundred to several thousand feet these areas are not profitably exploitable. Yet their location may lead to outcrops that may prove economically viable to future development.