The Clifton-Morenci mining district in eastern Arizona has a long history of mineral production.

It dates from the development of small oxidized replacement deposits by the Longfellow Copper Co., followed by the successful mining of enriched sulfide veins by the Arizona Copper Co., and by large-scale production of disseminated porphyry ore through open pit mining conducted by Phelps Dodge Corp in the 1930s.

Physiographically located between the basin and range and Colorado Plateau provinces in Arizona’s transition zone, the area is noted for its complex faulted plateau capped with volcanic flows.

Mineral discoveries in this remote area by Robert and James Metcalfe, along with Joe Yankie, prospectors from Silver City, New Mexico, in the fall of 1871 led to the establishment of the Longfellow, Detroit and Metcalf claims. Robert Metcalfe needed additional capital for development, and sold shares to the Lesinsky brothers, local merchants in Las Cruces, N.M.

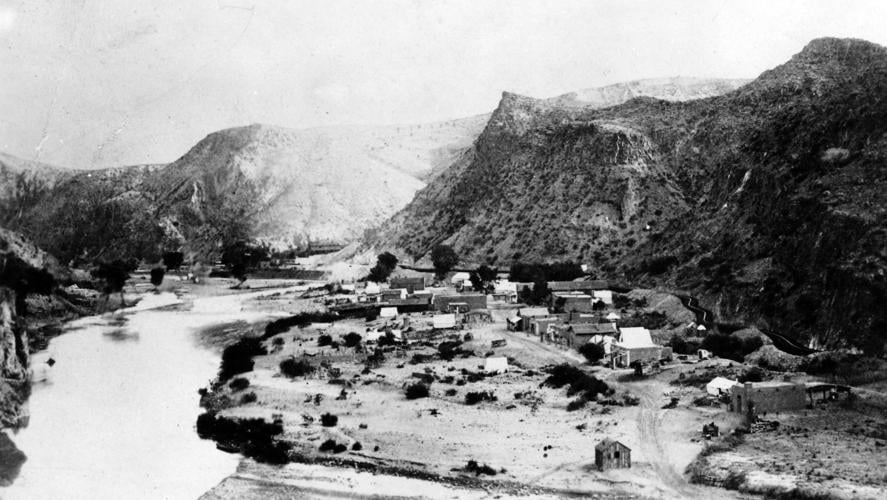

The town of Clifton was settled along the San Francisco River at the mouth of Chase Creek in 1873. Around this time the settlement of Joys Camp was established by mines north of Clifton at 4,800 feet in altitude with steep northern granite ridges.

The Longfellow Copper Co., one of the earliest mining companies in the area, was incorporated in 1874 by Henry and Charles Lesinsky, Eugene Goulding and David Abraham.

That same year, William Church from Illinois arrived in Joy’s Camp, later renaming it Morenci after a town in Michigan. He optioned multiple mining claims including Arizona Central, Copper Mountain, Montezuma and Yankee. With multiple mining interests (Metcalfe’s, Lesinsky’s, etc. involving adjoining lands) led to concerns over apex suits.

William E. Church sought to avoid such costly litigation by formulating an agreement among the owners of nearby claims to confine their operations to their respective vertical depths as laid out by their claim boundaries.

Similar agreements and contracts were made in other mining operations in Arizona, reducing the expenditure of capital and time in apex litigation.

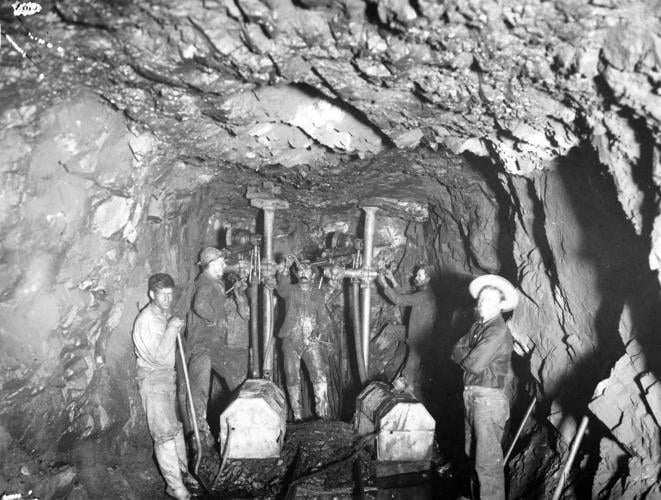

The Longfellow Mine was the principal operation in the Clifton mining camp during the 1870s, having produced 20 million pounds of copper averaging 20% ore. The property included multiple tunnels that entered the ore body several hundred feet below the mountain apex and were connected by winzes.

A product of Mexican artisans hired by Henry Lesinsky, Arizona’s first copper furnace located far below the Longfellow Mine was fed ore by a surface tramway from the mine. This wood- burning adobe smelter was fueled by nearby mesquite trees reduced to charcoal.

Daily production from self-fluxing ore consisted of several hundred pounds of black copper (95% pure).

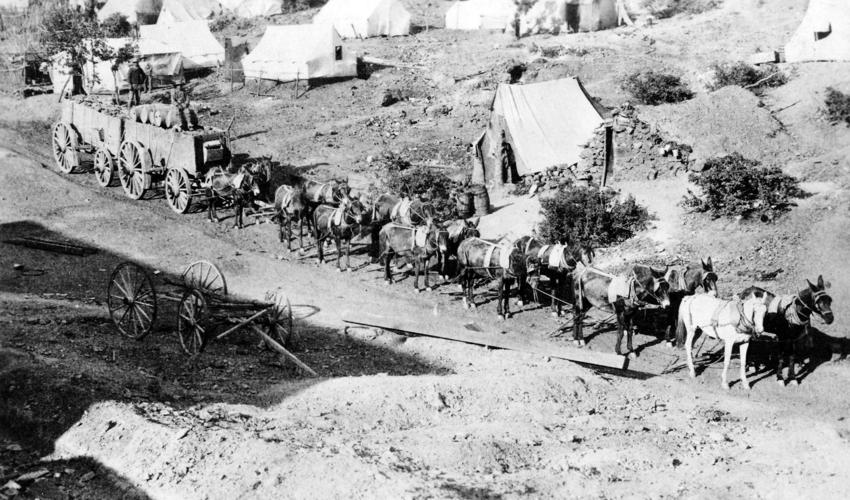

Transportation proved vexing as the closest rail access from the mines was 700 miles away at La Junta, Colorado. The copper ingots were transported by ox train over the Santa Fe Trail to market at Kansas City, 1,200 miles distant. During Apache raids, the drivers were killed, oxen eaten and copper bars having no intrinsic value to the Native Americans were left to be claimed by the next ore train.

Lesinsky’s early smelters proved crude, facing multiple operational challenges. Heat from the furnace often melted the smelter’s adobe walls. Attempts to refine the smelter with native stone construction failed, too, when the heat split the rock walls. Still other attempts included consultation with a German metallurgist from New York who spent eight months manufacturing a furnace with firebricks from local clay. Again, within 24 hours of use the furnace was reduced due to intense heat.

Louis Smadbeck, a cousin of Lesinsky and superintendent of the Longfellow Mine, finally resolved the problem by devising a furnace lined with an internal copper jacket that when sprayed with water would prevent melting. This larger smelter was built at Clifton, 5 miles below the Longfellow Mine, connected by a narrow 20-inch baby gauge railroad track. Ore cars were gravity fed and pulled by mules back up to the mine, until a small locomotive was procured for the task from La Junta in 1879.

An estimated 20 million pounds of copper were produced during the Lesinsky operation. Profits were modest and the Lesinsky brothers along with the Metcalfs were spread thin with financial investments including mines, stores, smelters and rail. The high cost of ore transport and structural concerns inside the mine necessitated their sale to Frank L. Underwood of Kansas City, who paid $1.5 million for their mining property around Clifton. Underwood in turn sold the holdings to a Scottish syndicate, the Arizona Copper Co., Ltd., comprising the Coronado, Longfellow, Crown Reef Humboldt, Bassett and other mines, for $2 million.

Despite early challenges the district faced, by the turn of the century, it was moving toward becoming the premier copper producer in Arizona, through the efforts of the Arizona Copper Co. to process low-grade sulfide ores and by the implementation of Arizona’s first copper concentrating plant in 1886 by the Detroit Copper Co.