Uranium production in Arizona dates to the late 1940s. Between 1948 and 1969 it produced 18 million pounds of uranium concentrate from over 300 mining operations.

The Sun Valley Mine, also known as the Maggie Baker, was one of those first developed in 1954 during the height of uranium exploration in the Southwest.

The mine was located at the base of the Vermillion Cliffs in Northern Arizona near the Utah border. It comprised the Sun Valley claims, totaling four, along with an additional 38 designated as the Jay Bird Claims. Initial exploration involved an inclined shaft sunk on a Shinarump outcrop of coarse sandstone and pebble conglomerate.

Mineralization was determined to be irregular with uranium samples as high as 0.216% taken from the U-shaped Shinarump stream channel occurring on the Shinarump Moenkopi contact. Uranium deposits appeared as ellipsoidal-shaped ore “pods” measuring 3 feet long by 2 feet wide.

A small shipment of several hundred tons of uranium ore was shipped from the mine to the Rare Metals Corp. Mill at Tuba City in 1956.

Around 195 feet of drifting began at the 45-foot level. Multiple drill holes totaling 8,000 feet revealed a potential ore body estimated to contain 5,000 tons assaying at 0.24% uranium ore.

Five men worked the mine, actively seeking funding from the Defense Minerals Exploration Administration to continue development.

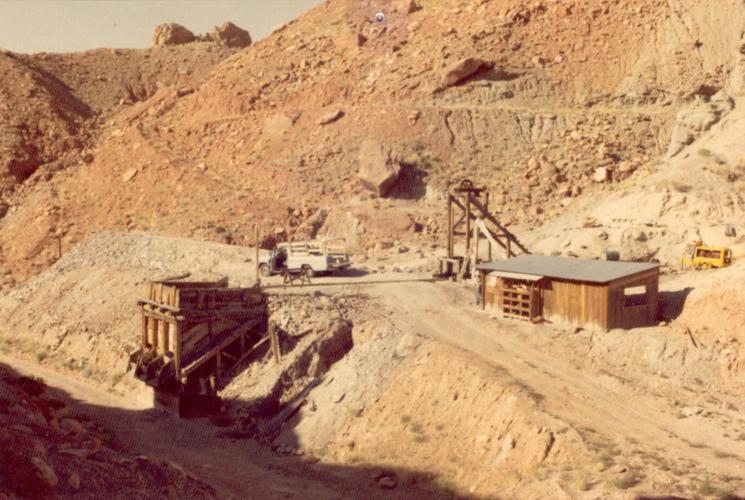

After an additional 100 feet of exploration and no confirmed ore discoveries, operations were suspended by the Bemco Uranium Co. in 1958. Development at the Sun Valley Mine had reached 400 feet of workings including a double compartment shaft reinforced with timber, wooden ladders, head frame and a 3 bin ore chute.

In 1975, the Intermountain Exploration Co. leased the property to Western Nuclear Corp., a subsidiary of Phelps Dodge. Exploration drilling was initiated with two holes bearing uranium quantities averaging 0.25% and 1%.

The Sun Valley Mine is also noted for containing unique concentrations (up to 0.07%) of water soluble rhenium salt. Early documentation revealed that the Sun Valley Mine was the only uranium deposit on the Colorado Plateau known to contain rhenium.

Confirmed by spectrographic analysis of onsite sedimentary rocks, amounts measured 0.005 to 0.1%. While rhenium is found in porphyry copper deposits such as Bagdad, Morenci and Sierrita in Arizona, it has also been found in sandstone-type uranium deposits including those at the Sun Valley Mine.

Considered one of the rarest elements in the world (less than one part per billion in earth’s crust), rhenium is valued for its heat and corrosion resistant properties. Its appearance is silvery-white, and its melting point is 3,180 degrees Celsius.

Recovery of rhenium as a byproduct is through the roasting process of molybdenite concentrates converted to rhenium oxide mixed with hydrogen gas to transform the rhenium oxide to the pure metal.

Rhenium is used in the manufacture of high temperature superalloys and in platinum-rhenium catalysts, which are used in petroleum refining. The aerospace industry employs rhenium for turbine blades used in jet engines.

Coconinoite, an iron aluminum uranyl phosphate sulfate hydroxide hydrate, is also found at the mine. This uncommon secondary mineral, named after Coconino County, occurs in seams 1 mm or less thick, in pale yellow, white-colored fine-grained thinly bedded arkosic sandstone. Another uncommon secondary uranium mineral found onsite is carnotite, a potassium uranium vanadate.

Exploratory operations ceased in the early 1980s, having confirmed that isolated uranium deposits were scattered along the Vermillion Cliffs.

Mining claims were abandoned around 1994, and the land reverted to the Bureau of Land Management in what became the Vermillion Cliffs wilderness in the Vermillion Cliffs National Monument.

The once prominent headframe collapsed in the late 1990s. In April 2014, the BLM installed a grate over the two-compartment shaft as a safety precaution. Mules were used to transport the grate to the mine as the use of mechanized equipment in the wilderness area was forbidden. A flash flood several years ago carried the once prominent ore chute away from the mine site.

The area was once considered to hold potential as a public use and interpretive site; however, the existence of low-grade uranium stock piles hindered BLM plans to move forward on account of potential health hazards.

Today the site can be accessed off Highway 89 near mile post 550 as a 2.4-mile round-trip hiking trail with impressive views of the Echo Cliffs, Houserock Valley and Marble Canyon.