The Old Pueblo Mine, also known as the Quien Sabe oxide copper deposit, was one of the earliest and last operating mining properties in what is known as the Amole Mining District.

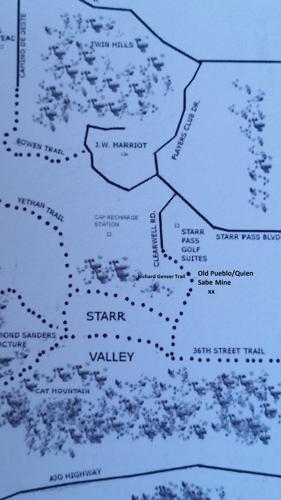

It is 7 miles west of downtown Tucson in the Tucson Mountains and is a prominent landmark in the form of a scar from mining operations over a century ago. Today it is panorama for hikers and bikers on the Richard E. Genser Trail and visitors and residents at the Starr Pass golf course.

The area is part of a large volcanic complex known as the Tucson Mountains volcanic caldera formed around 65 million years ago.

Original claims were staked in the 1870s by miners who spotted mineralization characterized by copper colorant along rock fractures at the surface. The first recorded development and production of the mine began in 1907 under the Tucson Consolidated Mining Co., which oversaw the property under a stock agreement with the Old Pueblo Mining and Milling Co. That year the main shaft was dug to a depth of 70 feet and workings totaled 600 feet.

Fifteen tons of chalcocite ore was sampled to assay at 33% copper, and 16 ounces of silver and $2.50 of gold was recovered.

Mining operations would remain sporadic over the next 63 years.

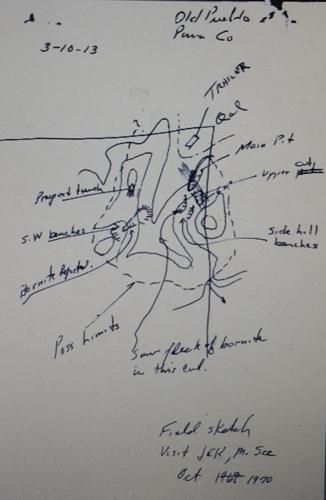

Sunk on a thin seam stained with green copper mineralization, the Quien Sabe shaft was reported in 1912 at a depth of 517 feet. A second shaft was 100 feet northeast of the main shaft on the northernmost outcrop of the main vein and 100 feet deep, with tunnels and open cuts.

By 1936, 67 tons running as high as 5% copper was reportedly produced.

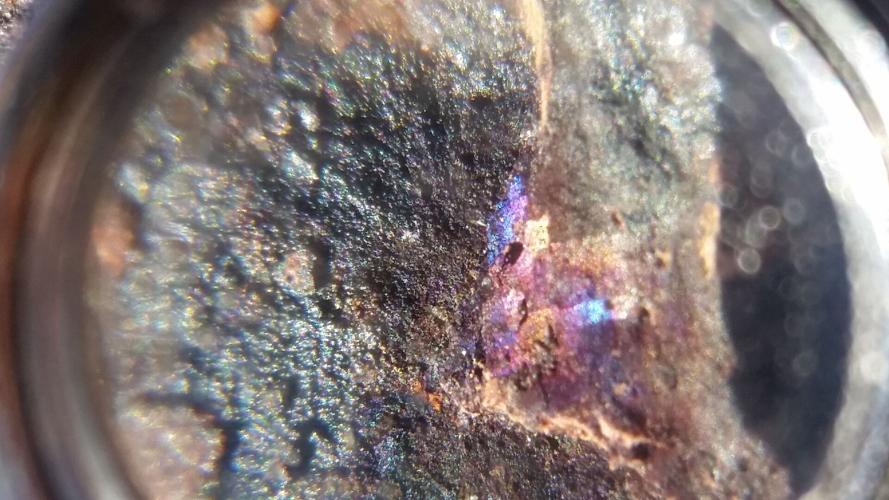

Interlaced quartz veinlet bearing secondary copper minerals in 7- by 8-inch andesite host rock specimen at Quien Sabe Mine.

Geology of the area is volcanic comprising rhyolite overlain by andesite, a well fractured host rock intruded by sericitized quartz monzonite.

The volcanic complex is comprised of thick welded ash-flow tuffs and chaotic megabreccia (coarse-grained rock composed of angular rock fragments in finer-grained matrix) formed from vents and volcanoes. Volcanic rocks date from the early Tertiary to the late Cretaceous time period.

Minerals found onsite include chalcocite and chrysocolla evident in mined open cuts, along with pyrite, chalcopyrite and bornite, first documented in retrieved core samples. Oxidation of the chalcocite by descending acidic ground water from the surface mixed with silica may have produced the chrysocolla deposits. Gangue materials, limonite and quartz are also found. Argillization, or the breakdown of minerals to clay from weathering due to water and air above ground, is common throughout the mine site.

The mine was also one of the last producing mines in the Tucson Mountains as reported in a combined production with the nearby Battle Axe Mine from 1969 to 1970.

Over 14,000 tons of smelter flux was shipped from the mine by McFarland & Hullinger of Toole County, Utah. The shipment contained a few tenths of a percentage of copper along with traces of silver and gold. Decorative stone was also produced.

Further exploration efforts undertaken by Cominco (Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada) included several drilling rigs on the property. Drilling of nine holes showed a large amount of copper oxides along with enriched chalcocite copper sulfide ore beneath barren-looking surface outcrops. Further drilling in the surrounding area revealed weak copper mineralization.

Evidence of a leaching operation using oxide materials from open cuts can be found in the wash west of the mine site.

Cominco dropped its option on the property in 1971.

While the property is documented as an interesting geological occurrence, it did not warrant further development based upon the disseminated ore values being too spotty and low grade for profitability, along with the increase in urbanization resulting from the Starr Pass Golf Resort.

Aptly christened Quien Sabe — translated to English as “who knows?” — the deposit is classified as protore, meaning that the rock contains potential economic material that may be mined at a profit at a later date under favorable economic circumstances coupled with technological innovations in mineral extraction.

The deposit may also become more enriched, yielding greater economic value through the natural processes including supergene enrichment caused from chemical weathering and precipitation above the surface.

Remnants of a leaching operation in a nearby wash west of the Quien Sabe Mine.

Map depicting Old Pueblo Mine in relation to Tucson Mountains.

Prominent open cut of Quien Sabe Mine looking south from Richard Genser Trail.

Silica veinlets on 6- by 8½-inch andesite porphyry specimen at the Quien Sabe deposit.

Micro specimen of bornite seen through a hand lense at Quien Sabe mine site.

Manganese dendrites found on 3- by 6-inch sandstone bearing secondary copper mineralization at Old Pueblo Mine.

Secondary copper mineralization colorant on 6- by 10-inch andesite.

Field sketch of Old Pueblo Mine site circa 1970.