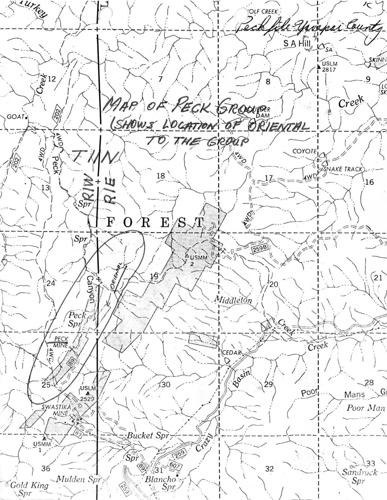

The Peck mining district in the Bradshaw Mountains comprised several prominent mines including the Peck, Swastika, Breslin and De Soto.

The Peck Mine, at 5,500 feet in elevation, was the most economically profitable between 1875 through 1885. Producing over $1.2 million in silver, it was one of the most productive silver mines in Yavapai County.

Edmund George Peck, the mine’s namesake, arrived in Northern Arizona from Santa Fe, in what was then the New Mexico Territory, in 1863 after hearing about the successes of the famed Walker Expedition involving the discovery and working of gold placers along Lynx Creek earlier that summer.

Peck, a former Army scout stationed at Fort Whipple north of Prescott in the late 1860s and former squad commander under King Woolsey’s second Apache Expedition, was drawn to prospecting the Bradshaw Mountains, renowned for relatively shallow ore deposits.

It was in the summer of 1875 that Peck discovered a ledge of silver ore at the future mine site, enticing his partners Curtis Coe Bean, William Cole and Thomas M. Alexander to invest money and labor in development after returning to Prescott with over 100 pounds of ore assayed at over $13,000.

The geology of the mine property is comprised of Precambrian schists and granites with silver and minor gold found in quartzite and rhyolite fissure veins and three parallel ledges rising more than 15 feet above the surface.

Silver mineralization was discovered in the form of cerargyrite — horn silver — along with small amounts of embolite and bromyrite. Trace amounts of argentite and gold were also discovered at the site along with some copper, antimony and zinc from sulfide ore discovered at the lower mine levels. The Occident Mine was developed on a parallel ledge to the Peck Mine along with the Silver Prince and the Black Warrior extension.

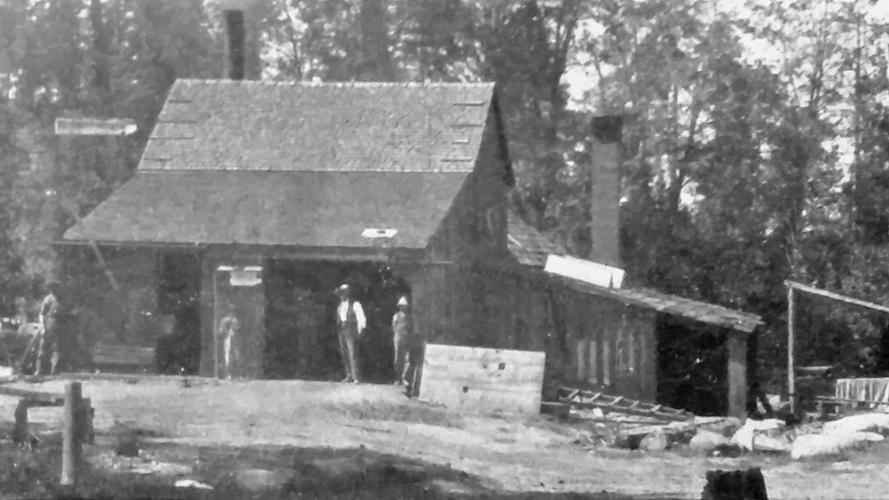

Named after Mrs. T.M. Alexander, the wife of one of the mine’s partners, the nearby townsite of Alexandra in Peck Canyon came into prominence by 1876 with 70 buildings, including three boarding houses and four saloons, built to accommodate more than 60 men working the mines.

The Peck was in its prime with its main shaft sunk to a depth of 230 feet and a 275-foot-long tunnel, with ore production valued between $1,000 to $3,000 per ton. Timber was secured from the nearby Del Pasco Ridge, and water was acquired from the mine, which produced 2,000 gallons every 24 hours.

Severe legal problems arose in June 1876 that were to plague the mine operatives for the next five years.

These began when one of the mine’s discoverers, William Cole, went on a drinking and spending spree culminating in his deeding away portions of his interest in the Peck Mine. His fondness for whiskey was said by Cole himself to have been perpetuated by a tapeworm in his gut that necessitated strong drink. Litigation among the miner owners and operatives commenced, causing the mine to shut down for extended periods while eroding profits that went to lawyers.

Yet, 1877 was a prosperous year for the Peck Mine. A rich sample of ore discovered in the north tunnel of the Peck Mine assayed at over $17,000 per ton. Employment ran high, with more than 150 miners and a monthly average shipping of ore valued at $50,000. Improvements on the property included a wagon road from the mine to the mining camp’s supply depot in Prescott and the erection of a $75,000 onsite 10-stamp Aztlan mill to reduce the costs of freight transport.

The passage of the Bland-Allison Act, requiring the U.S. Treasury to purchase specified amounts of silver for circulation as silver dollars in 1878, remonetized silver, helping to sustain the Peck Mine and other prominent silver mines in the West.

By 1885, the main shaft had been sunk to a depth of 400 feet divided into four levels of operation aggregated at 1,400 feet in length. Shortly thereafter, the mine played out either because of faulting or diminishing ore.

Subsequent attempts to make the mine a major producer failed. The mine dumps were worked intermittently by lessees thereafter, with no significant production recorded.

Map of the Peck group of Mines and their surroundings.

However, some tailing ore was retrieved through crushing, screening and gravity separation, with concentrates shipped to smelters at Humboldt around 1924 and the Asarco smelter in Hayden. Early remnants of cyanide leaching were also evident .

Later attempts to reopen the mine found the investment for drilling exploration to be greater than the value of the mine’s reserves.