The most prominent mining operation in the Baboquivari Mountains was the Allison Mine, yielding gold and silver.

Located on the western slope of the mountains, in the Fresnal Mining District, it was originally discovered by Ricks and Bourse (first names not available) in 1888. Production did not occur until the Allison brothers bought their interest a decade later. A 21-mile road running to Sells was soon built for ore transport on to Tucson, 60 miles distant. Ore was taken to the town of Fresnal for processing.

The Baboquivari Mountains, a long, intrusive granitic outcrop, saw mining operations conducted by the Spanish in the early 1700s. Spanish miners were attracted to deposits of acanthite and chlorargyrite and argentiferous galena found in the tilted thick conglomerate beds intruded by rhyolite dikes and andesite porphyry containing thin stringers of gold-bearing quartz veins.

In 1898, with a 100-foot shaft sunk, a small amount of gold ore was removed from the Allison Mine. The superficial nature of the ore hindered further work on the mine site until a 450-foot adit tunnel was driven beneath the old mineshaft in 1923, which connected to an underground hoist chamber at the 200-foot level. A 10-stamp mill was soon built and the recovery of gold-silver bullion followed. The ore was hoisted to pockets above the 200-foot level, then hand-trammed to the surface for storage until it was hauled by truck to the railroad connection in Tucson. An on-site cache of lower-grade ore valued at less than $10 per ton was left in reserve to mill at a later date. Some ore mined at the 500-foot level assayed as high as $384 per ton.

The Tom Reed Gold Mines Co. acquired the lease in 1926, extending underground mining while establishing an on-site flotation mill for the contiguous group of 13 unpatented mining claims. Two years of production yielded 2,176 ounces of gold and 44,705 ounces of silver valued then at $109,960. The large amount of manganese oxides made the gold-bearing ores refractory, hindering the cyanidation process by consuming the cyanide reagent before it could solubilize the gold, impeding recovery. Additional composition of the ore included calcite along with small amounts of hematite and pyrolusite and gold accompanied with silver at a weight ratio of around 22 to 1.

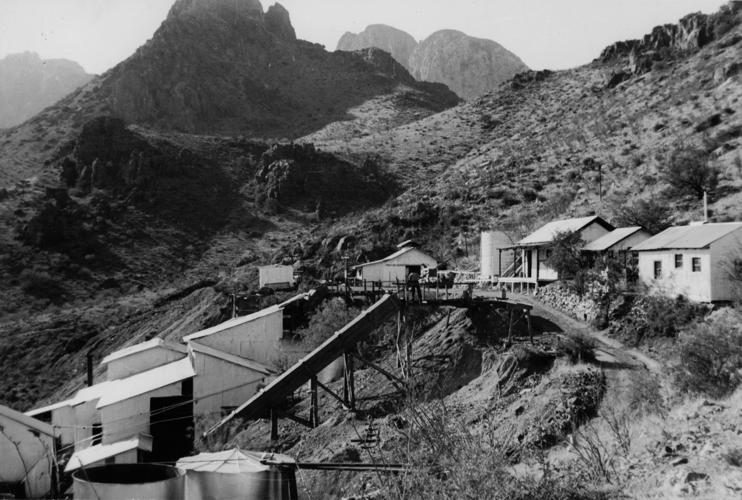

Located 1 mile northeast of the Allison Mine was a mining camp that included a mill, assay office, blacksmith shop and various equipment ranging from two air compressors to a light service truck. Water was obtained from a nearby 20-foot-deep well producing up to 16 gallons per minute and pumped to the camp by a 3-inch pipeline. A large reservoir, including a 35-foot-high, 6-foot-wide and 43-foot-long concrete dam was used for collecting floodwater to operate a 50-ton cyanide or flotation mill. Expectations were 50 to 100 tons of ore per day.

Lessees and operators including the El Oro Mining and Milling Co., which produced $5,500 gold-silver bullion in 1930 and continued to operate the mine intermittently for several decades.

A geological assessment in 1940 conducted by consulting geologist Guy W. Crane marketed the Allison group of mines as having deposits similar to those of other renowned mining camps including Oatman, Katherine, Mammoth and Kofa, all of which were notable for bonanza ore shoots having produced nearly half the gold output of the state.

Although not a sizable producer, the Gold Bar Mining Co. erected a cyanide plant and mill on-site in 1941, employing 32 miners. Production was limited to 10,000 tons, and $61,000 worth of bullion was shipped to the U.S. mint in San Francisco. By that time, the Allison vein was penetrated by an incline shaft that reached to a depth of 625 feet consisting of latter workings for an overall development of 3,500 feet. Other notable veins included the Fourth of July and No. 3. The operation was shut down in December 1941 by the U.S. government because of the lack of strategic metals produced.

Maurice Hederman, from Sells, leased the property in 1959, shipping high silica ore with gold and silver as flux to the Ajo smelter, producing 500 tons per month. The mine was closed permanently in 1961, with 20 unpatented claims owned by the Sawyer Petroleum Co. of California.

In 1966, an induced polarization survey was conducted on a select part of the mine by the Heinrichs Geoexploration Co. for North American Mine Inc., prior to the land reverting to the Tohono O’odham (then Papago) Tribe in the 1980s.