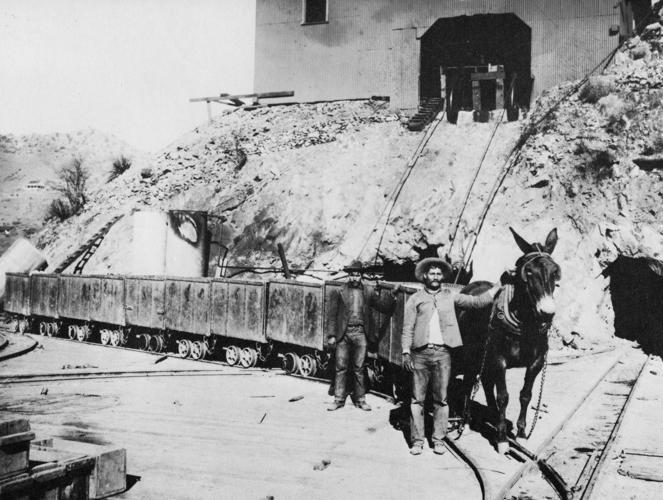

Ore-hauling animals contributed economic savings and production to many of Arizona’s mining towns and camps of the past.

The expense of underground transportation constitutes a considerable percentage of the total mining cost in most mines, exceeding at times the expenditure of stoping (opening large underground rooms by removing ore), the Bureau of Mines has observed.

In the early years of underground mining in Arizona, miners known as trammers were responsible for pushing ore-laden carts. As mines became more developed, in excess of 500 feet, this operation became less efficient.

Mining companies found a solution, using animals to improve efficiency and economy for long-distance hauling.

Mules, draft horses, burros and oxen were traditionally credited with having participated in overland ore transport. Also supplying the power for hoisting material to the surface, they were later replaced by steam engines using steam from a boiler assembly.

Mule teams transported copper bars from the mines at Clifton-Morenci 1,200 miles to Kansas City, the closest railhead and access to markets.

Local transportation in mining towns also relied upon animal s. The Detroit Copper company store at Morenci offered the option to residents of home delivery for grocery supplies by burro or mule. Burros could also be seen transporting water in two canvas bags holding 40 gallons. The average cost was 50 cents a load.

Oxen were the beasts of choice for freighting ore from the mines in Bisbee and Morenci.

Mules have historically been the preferred animal for transport, weighing between 800 to 1,200 pounds. Mules are smaller than draft horses, require less headroom, have the ability to endure heat and are more robust when compared to the horses. They are less likely to become lame.

Unlike horses, which are prone to smash their heads against a low-lying underground drift, a mule would duck its head to avoid such a collision.

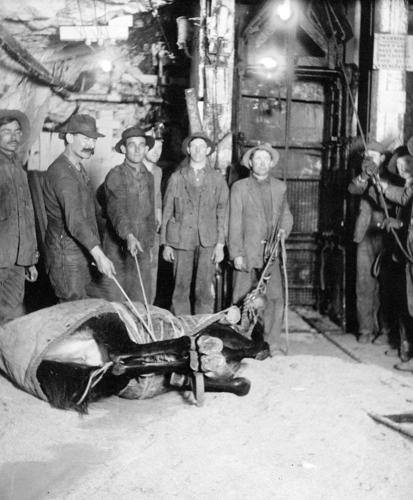

The cost of procuring good mules for mining operations ranged between $150 to $300, taking into account their condition, age and weight. Mules were expected to work underground between three to seven years. Afterward, they were retired, being brought to the surface at night and slowly re-exposed to daylight by being kept in a dark room lit by candlelight with increments of exposed daylight over the course of several weeks. Then, they were set free to run wild.

Mining operations at Bisbee relied upon mule haulage or tramming beginning in 1907, continuing through 1931. Earlier operations relied upon the miners themselves to move the ore cars by hand.

Obvious limitations arose, since miners could only tram a single loaded car in contrast to mules, which could move five or more cars. The cars weighed 800 pounds empty and around 2,800 pounds full. Mules possessed enough acumen to realize their limitations. When miners attempted to add extra cars , the mules chose not to move until the additional weight was removed.

Mules and horses working underground on average traveled 3 to 15 miles per shift.

A mule school existed at Bisbee on a hillside above Brewery Gulch to train young mules for underground mining. The school was composed of a circular track, one switch and 30 feet of straight track on a flat surface of the hill. Working without bridles or reins, mules were given their daily lessons of waiting at ore chutes until cars were loaded and directing cars by kicking switch points along the track with their hooves. They became proficient at gathering ore-laden cars from the loading faces to a siding on the main haulage way, afterward returning the empty carts.

They also quickly learned to follow voice commands, in many cases in different languages depending upon the miners’ ethnicities.

The adaptation of electric power, coupled with the introduction of the diesel engine and storage battery for trolley locomotives, reduced the use of animals.

Rising costs also had a formidable impact, including those incurred by feeding (corn, oats wheat and barley) and general animal care. There was also the cost of building underground stables to house mules along with the need for veterinary attention and blacksmithing to shoe the animals.

Overall, the contribution of animals was significant.