When Yonas Kahsai was first transferred to the state prison in Tucson, the other inmates didn’t want to know what he was in for. That would come later. They wanted to know if he had been tested for COVID-19, if he was positive.

This was a general shift in prison-yard culture that Kahsai and others noticed during the pandemic. Kahsai said the state transferred him to Tucson in September. This was right after a major outbreak infected hundreds of inmates in Tucson. When he got there he noticed the inmates were scared and on edge.

Kahsai said the prison guards would take advantage of this fear when inmates acted out. He said he heard guards threaten to infect inmates by coming to work if the guards themselves happened to get infected. He couldn’t tell if these guards were being serious or not, but either way it really bothered him.

Kahsai was scared. He didn’t want to get sick and he didn’t want to bring the virus home when we would be released towards the end of February after serving his term for armed robbery.

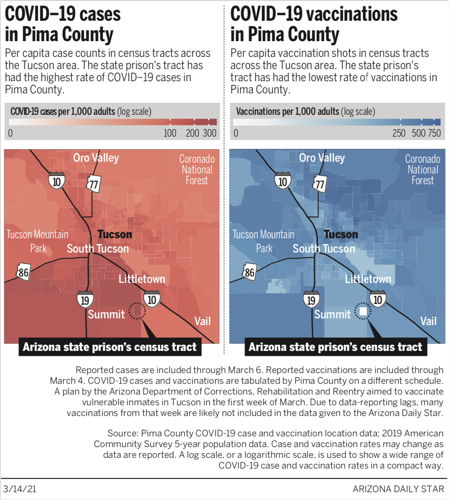

He had been transferred to one of the places in Pima County hardest hit by the pandemic. The state prison’s census tract in Tucson has had the highest rate of COVID-19 and the lowest rate of vaccinations in the county.

The state prison complex in Tucson has its own census tract, numbered 41.13. Nothing else but the prison complex is located there.

So far, it has the highest cumulative case rate and lowest vaccination rate per capita in Pima County, whether the rate is calculated using the total population or just the adult population, according to an analysis by the Arizona Daily Star. The Star looked at population estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, along with COVID-19 case and vaccination data provided by Pima County.

High risk

Knowing which places have high cumulative rates of COVID-19 cases can help health officials decide where vaccinations are needed most, said Dr. Joe Gerald, an associate professor with the University of Arizona’s College of Public Health.

Places that have had the most cases per capita are often at higher risk for more infections. “It’s somewhat of a counterintuitive finding,” Gerald said, because you might think more cases in one place might mean more potential natural immunity there, too.

He said that, for certain people in these hard-hit places who have not been infected, they’ve dodged a bullet, but more will likely come their way. The risk isn’t over.

“It’s (a finding) that we in our group here at the University of Arizona are very convinced of, which is, we need to do more to target vaccinations in areas with high past burden of COVID-19 disease because that’s an indicator of current risk.”

The Star didn’t include census tracts in the Tohono O’odham Nation on the “main” reservation in the analysis because the county could not geocode many of the addresses there, which is a process for assigning latitude and longitude coordinates to addresses. A county health official said the level of vaccine distribution seemed better in the Tohono O’odham Nation than at the state prison.

Vaccination progress unclear

A plan by the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation and Reentry aimed to vaccinate 181 vulnerable inmates in Tucson from March 1-5. These inmates include those in the infirmary and the Special Needs Unit in Tucson.

According to the plan, state inmates in Tucson who have high-risk medical conditions and those who are at least 65 years old are also scheduled to be vaccinated the week of March 29-April 2. They are scheduled to receive their second dose the week of April 26-30.

Attorneys at the American Civil Liberties Union got the vaccination plan from attorneys for the Department of Corrections after asking for it repeatedly, said Corene Kendrick, deputy director of the ACLU’s National Prison Project.

This was possible due to a 2014 settlement reached in a case called Parsons v. Shinn, which dealt with health care. “(The plan) doesn’t look very official and it’s not on the (Department of Corrections’) website, which is a little concerning,” she said.

The department didn’t respond directly to the Star’s inquiries about the plan’s details or the department’s follow-through.

While county officials gave the Star vaccination data though March 4 and the Department of Corrections planned to vaccinate the most vulnerable inmates by March 5, many vaccinations from that week are likely not included in the Star’s dataset due to data-reporting lags.

If the department did vaccinate these 181 vulnerable inmates in Tucson, however, the state prison’s census tract would still have the lowest vaccination rate per capita in the county.

The county’s chief medical officer, Dr. Francisco Garcia, said on Friday that he is seeing around 100 vaccinations from the state prison’s census tract in more recent data that he hasn’t released yet because the data haven’t been cleaned or processed.

State health director Dr. Cara Christ said on Friday that she had recently received an update from the Department of Corrections that it has started vaccinating in the infirmaries and “another high-risk unit.”

When asked for the specific number of inmates who have been vaccinated, she referred the question to the Department of Corrections.

In an email on March 8, a spokesman, Bill Lamoreaux, said, the Department of Corrections “is currently providing the opportunity to receive a vaccine across the department for Centurion healthcare workers who are part of the 1A frontline healthcare group and correctional officers who are part of the 1B protective services personnel group.” Centurion is the health-care provider for state inmates.

As for vaccinations for the inmates, Lamoreaux wrote that some qualify, but the department “is prepared to offer the vaccines to inmates upon distribution,” suggesting that they have not been vaccinated yet.

The department didn’t directly answer multiple attempts by the Star last week to clarify whether, or how many, inmates have been vaccinated statewide and in Tucson.

In a subsequent email, Lamoreaux did include a link to a January news release that said “the anticipated administering of vaccines to our vulnerable inmate population is dependent on the number of vaccines received, and locations where they are received.”

”Black hole” of information

Pima County public health officials don’t know much more than the general public about COVID-19 in the state prison. Garcia called the federal and state prisons a “black hole” of information. Throughout the pandemic, he’d only learn about COVID-19 outbreaks in these prisons when he’d see flare-ups in the data.

The amount of information about COVID-19 coming from state prisons is especially frustrating for families and friends of inmates.

For example, Nkenge Simpson’s son, Marcellus Jackson, is incarcerated at the state prison in Tucson. She worries every day about him contracting COVID-19.

She said her son is currently in a detention center within the prison. Simpson said it’s also known as “the hole.”

In a letter she read to the Star, Jackson wrote that he’s the third person in a cell meant for two people, where he’s sleeping on the floor a few feet from the toilet.

He’s also depressed due to prison visits not being allowed during the pandemic, Simpson said.

State records show Jackson has been convicted of armed robbery and burglary.

Simpson doesn’t know when he will be offered a vaccine, but every morning Simpson checks the COVID-19 numbers on the Department of Corrections’ online dashboard.

This has been her routine for nearly a year, even though she doesn’t trust the information on the dashboard. She thinks the numbers are worse than what’s reported.

She said her son was transferred to Tucson around the end of December. This made her nervous because she knew the official case counts there had been high.

“I was already stressed with him moving to Tucson because I’m one that I get up, unfortunately, and I look at the stats ... even though I know they’re wrong,” she said. “And I look at the number of deaths, the number of people sick, the number of staff infected.”

This distrust of the official numbers is common for friends and families of those incarcerated in the state prisons. When the Star pointed this out to the Department of Corrections, Lamoreaux wrote, “all inmate deaths are investigated in consultation with the county medical examiner’s office. COVID-19 data continues to be updated on ADCRR’s dashboard.”

Outbreaks can spread beyond prison walls

Gerald said he’s been worried about prisons in the pandemic for some time.

“They’re definitely a high risk setting given the often crowded conditions and close confines that inmates must share,” he said, adding that this makes it ripe for the transmission of a communicable disease like COVID-19.

Both Gerald and Garcia point out that whatever happens inside prisons may eventually affect the larger community. The virus doesn’t care who was sentenced to prison and who works there. Eventually COVID-19 outbreaks can spread beyond the prison walls.

Beyond how the prisons can affect the larger community, Gerald said there’s also a moral responsibility at play since inmates are wards of the state, and of the public by extension.

“We have an even greater responsibility to ensure that they have access to care and testing and vaccines, things of that nature, because in all other regards, they lack free will and are totally dependent on us for their safety and wellbeing,” he said. “It’s important to think about the prisoners because they’re human beings. Just because you’ve committed an offense, you don’t surrender all of your rights as simply being a member of the human species.”