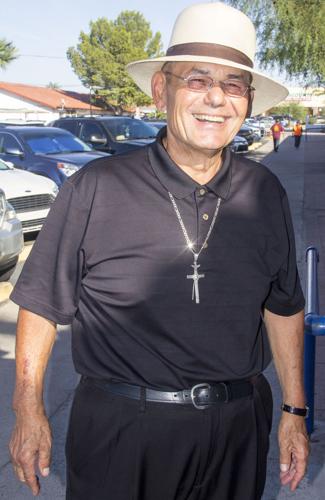

As a Catholic priest, Monsignor Raúl Trevizo kept visiting sick people during the pandemic, even a few with COVID-19. He knew it was a risk, and part of him did feel scared.

He would pray with them and anoint them with oil, using a cotton ball instead of his fingers, while wearing a mask and gloves.

He was administering the Catholic sacrament, the anointing of the sick. This is why he was willing to take the risk and go a few times to homes where he knew people had been contagious. He and other priests would do this, he said, so that if the sick died, their sins would be forgiven.

Many of his parishioners and those in the surrounding area are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 for a variety of reasons. So, when the opportunity arose to host one of Pima County’s mobile vaccination clinics at Trevizo’s church, St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church at 602 W. Ajo Way, he embraced it.

It was a deadly winter for his church. One week in January, he said, he held three funerals for members who died of COVID-19.

The virus has taken 10 to 15 members in total, although he can’t easily remember the exact number. It became a common way to die, blending into the many causes of death that he helps families cope with. And even more of his parishioners fell ill from it. Trevizo himself had a mild case of COVID-19 in November.

“It just didn’t seem to make any sense how it attacks people and who died and who got very sick and who had a mild case,” he said.

He saw the mobile vaccination clinic as a way to try to stop the many COVID-related illnesses and deaths in his community.

For Olivia Lopez, 73, and her husband, Eddie Lopez, 79, it meant some relief to an isolating year when they were vaccinated in February at Trevizo’s church.

Their kids would bring them groceries, but during the lull in cases, before the winter surge, Olivia convinced her kids to let her go to the store on her own. It didn’t last long, but it helped her feel better. She said it helped her regain her sanity.

For Pima County health officials, Olivia and Eddie Lopez were exactly the people they wanted to vaccinate at the mobile vaccine clinic at the church.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo is highlighting the Javits convention center in New York as an effective COVID vaccination site, but he stressed that Blacks and other minorities are not receiving the vaccines equitably.

They are older than 65 and Latino. Plus, registering online for the vaccine had been a tremendous struggle for them. At the mobile clinic, they could just walk in.

County health officials at Pima County use data to decide where to send mobile vaccine clinics, which they use to target certain groups, especially older people of color who aren’t as tech-savvy.

These health officials look at metrics such as the rate of cases and deaths per capita, along with an area’s social vulnerability, which is measured by an index of U.S. census data on income, age, race, language, housing type, occupation, education attainment, access to transportation and more. This index is meant to help officials find areas that may need additional support preparing, weathering and recovering from disasters or hazardous events.

Data on age and race from the county’s mobile vaccine clinics show that Pima County is vaccinating the vulnerable people it wants to reach at these clinics. In that regard, these clinics are working.

But the effect is not yet visible when looking at countywide vaccination data.

While available vaccination data on race and ethnicity at the county level suggests that whites have been vaccinated at a disproportionately higher rate than people of color, the story is different at the mobile vaccine clinics.

The county’s data show that these clinics do reach a higher proportion of people of color.

Some areas still have low vaccination rates

About 251,000 people have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine in Pima County, according to the Arizona Department of Health Services’ online dashboard. The state did not know the race of 24.8% of these people as of Saturday.

The state did know that 41.8% of these vaccinated people have been non-Hispanic whites. Only 15.3% of vaccinated people have been Latino or Hispanic.

Meanwhile, in Pima County, about 51.7% of the population is non-Hispanic white and 37.2% is Latino or Hispanic.

The state health department does not expect the demographic breakdown of vaccinated people to align with population demographics because of the phased approach of vaccination distribution.

This is because the groups that were prioritized first for the vaccine were already whiter than the general population, said Dr. Joe Gerald, an associate professor with the University of Arizona’s College of Public Health.

For example, he said, the proportion of the population over 75 years old that’s white is larger than the proportion of the population under 30 years old that’s white.

While the proportion of people of color who have received a COVID-19 vaccine has not matched the overall population breakdown at the county level or the state level, people of color are overrepresented at the mobile vaccination clinics. And that’s what health officials want to see because people of color have been underrepresented as a whole.

For example, 80% of those vaccinated at St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church were Latino.

And in late February, 34% of those vaccinated at a clinic at Rising Star Baptist Church, 2800 E. 36th St., were Black. About 3.3% of the countywide population is Black.

While county health officials have race and ethnicity data on mobile vaccination clinics, the county does not have data on other social vulnerability indicators, like income and occupation, from the patients at these mobile clinics.

While the mobile clinics seem to be working on a case-by-case basis, there are still pockets of the city they have not reached.

Some census tracts in Pima County with the highest COVID-19 case rates per capita still have relatively low vaccination rates. Census tracts are areas roughly equivalent in size to neighborhoods.

Census tract 39.01, for example, which is near Nebraska Street and 12th Avenue, had one of the highest rates of cases during the winter surge, but its vaccination rate ranks in the bottom half of all tracts countywide. Its social vulnerability score is also relatively high, coming in at 0.84 on a scale from 0 to 1.

The Star looked at vaccination data through March 17. On March 16, however, the county held a mobile vaccination clinic at Vida Nueva Church of God, 330 W. Nebraska St., which is located very close to census tract 39.01. Results from this clinic likely have not shown up in the vaccination data because of general lags in the data-reporting process.

The thing limiting the county most from doing even more of these mobile vaccination clinics is staff capacity, said Jess Seline, the county’s health equity program manager. Next is how mobile vaccination clinics are prioritized for vaccine allocation.

While mobile vaccination clinics can reach the most vulnerable people, Gerald said, allocating more vaccines to federally qualified health centers and to local pharmacies in places like grocery stores are other strategies he would like to see state vaccine allocation strategies prioritize.

Over the next month, Bonnie LaFleur, a biostatistician at the University of Arizona, expects to see vaccination rates climb in areas of Pima County that have higher social vulnerability scores.

She said this will likely be the result of both the county’s mobile health clinics and a widening of vaccine eligibility.