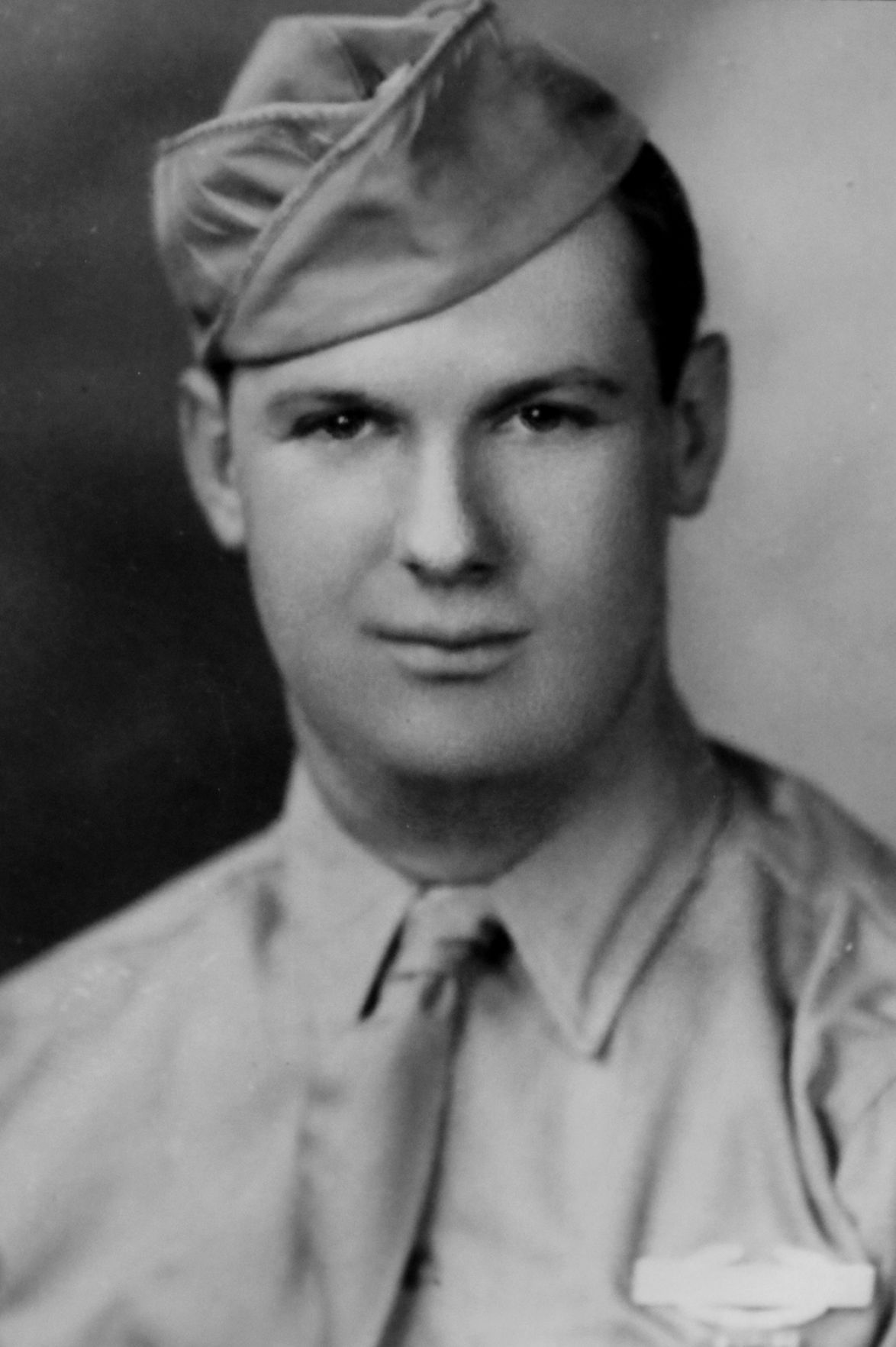

The Veterans Memorial Overpass in Tucson honors all who have served our nation’s military, including Eddie Araiza, who went from being a ranch and racetrack hand to patrolling European bases as part of a military police company during World War II.

Eddie was born in 1924 in San Bernardino, California, after his parents, Alfredo and Francisca, moved there in 1922 to continue working for the Isaacson family, who had moved their cattle operation from Southern Arizona. They moved there with Alfredo’s sisters, Ernestine Araiza and Sarah Salaz.

In 1926, Eddie’s parents returned to Arizona to live with family near Cascabel, along the San Pedro River north of Benson, because Francisca had developed tuberculosis. She soon died.

Alfredo remarried, to her sister Isabel. They would have children Ernesto, Helen, William and Mary.

Eddie stayed in California with his aunts until he was 5 years old.

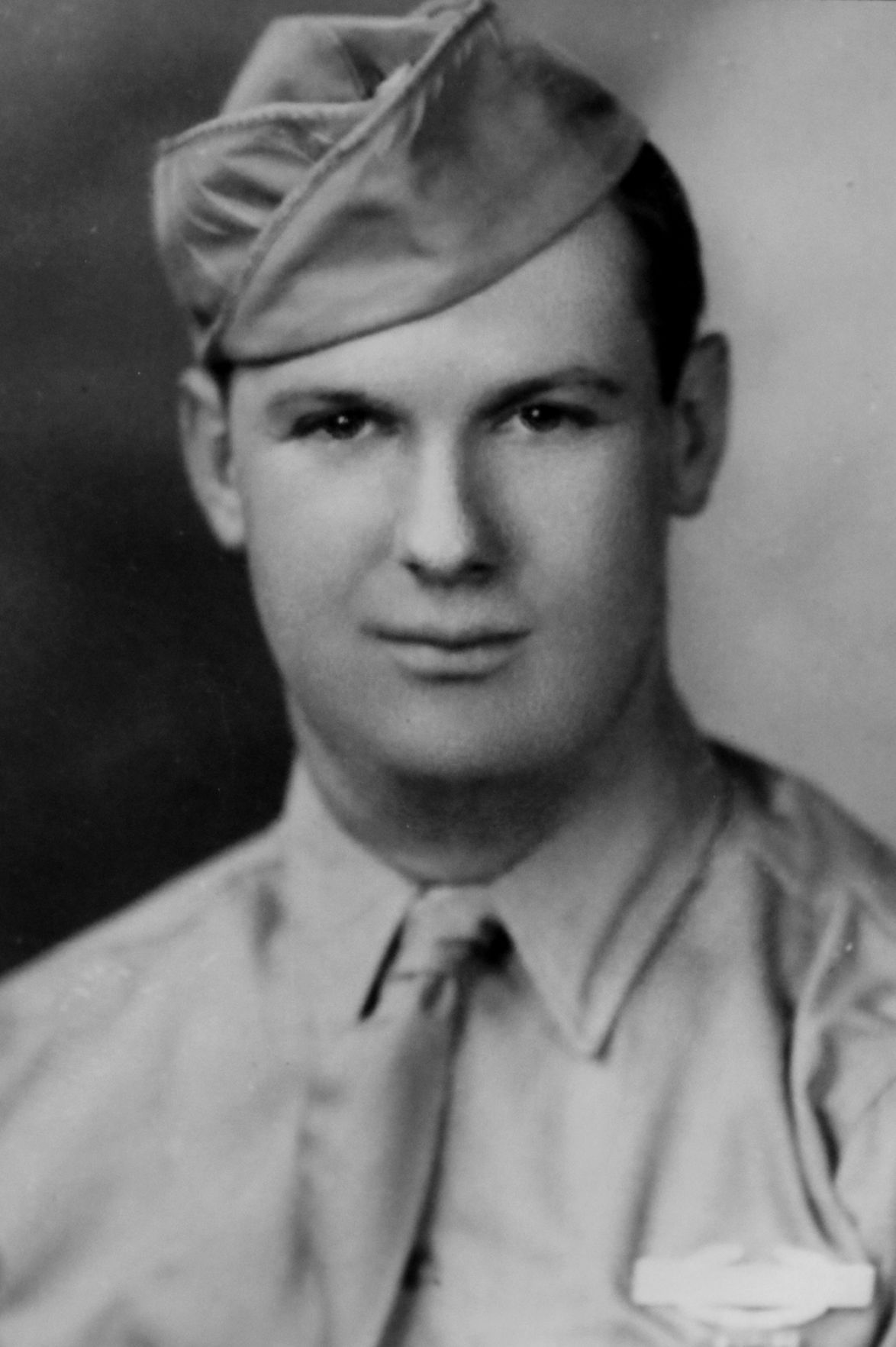

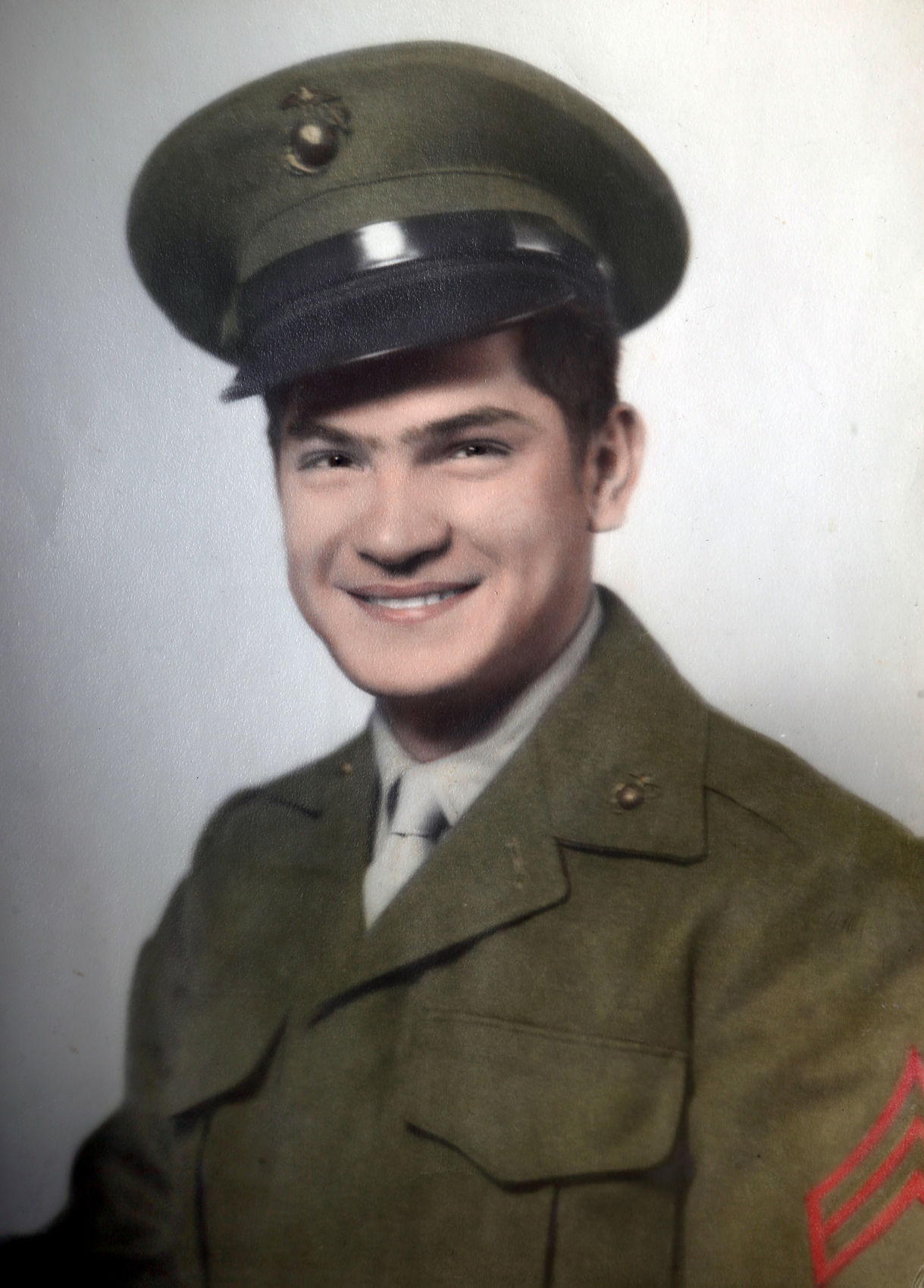

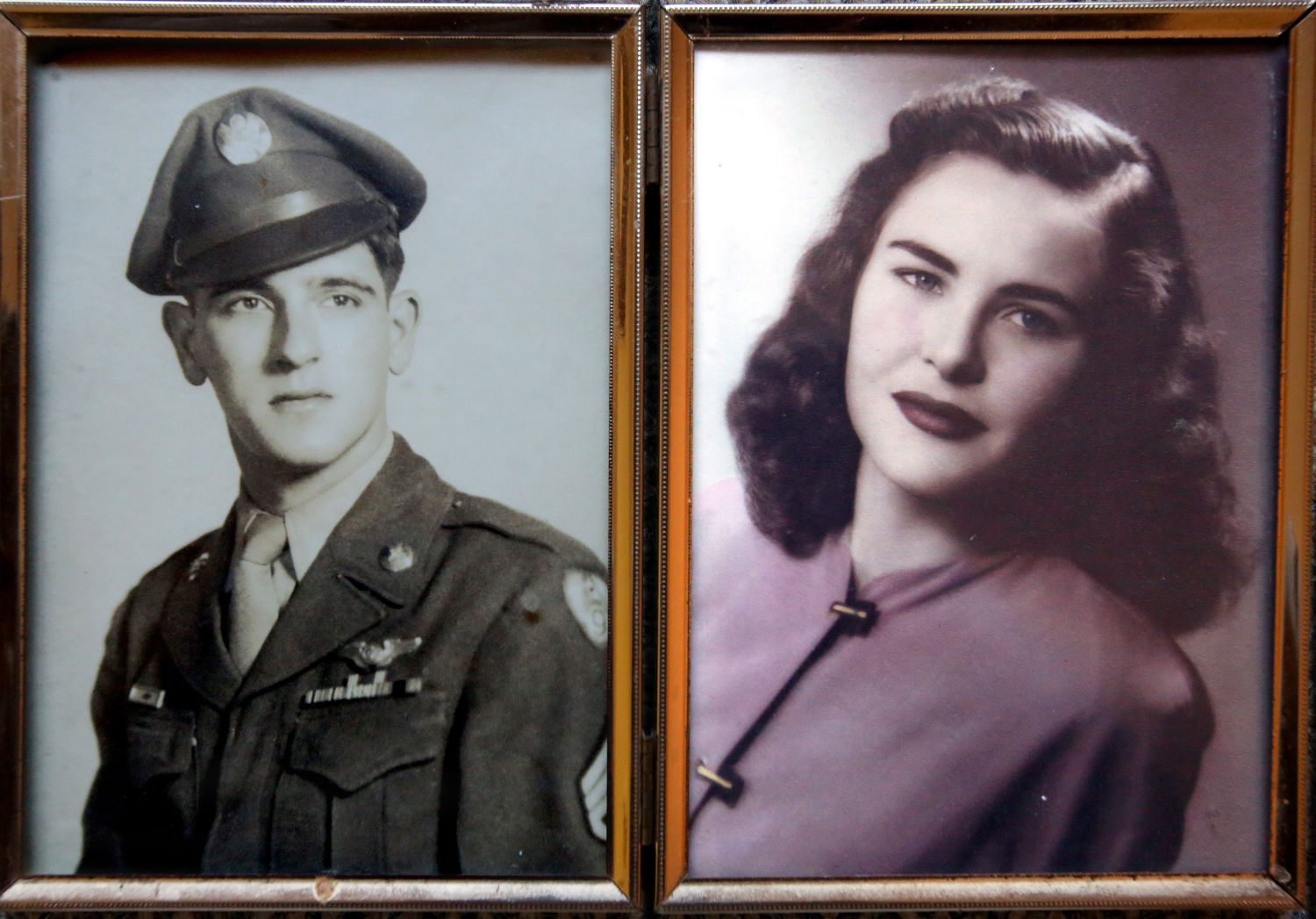

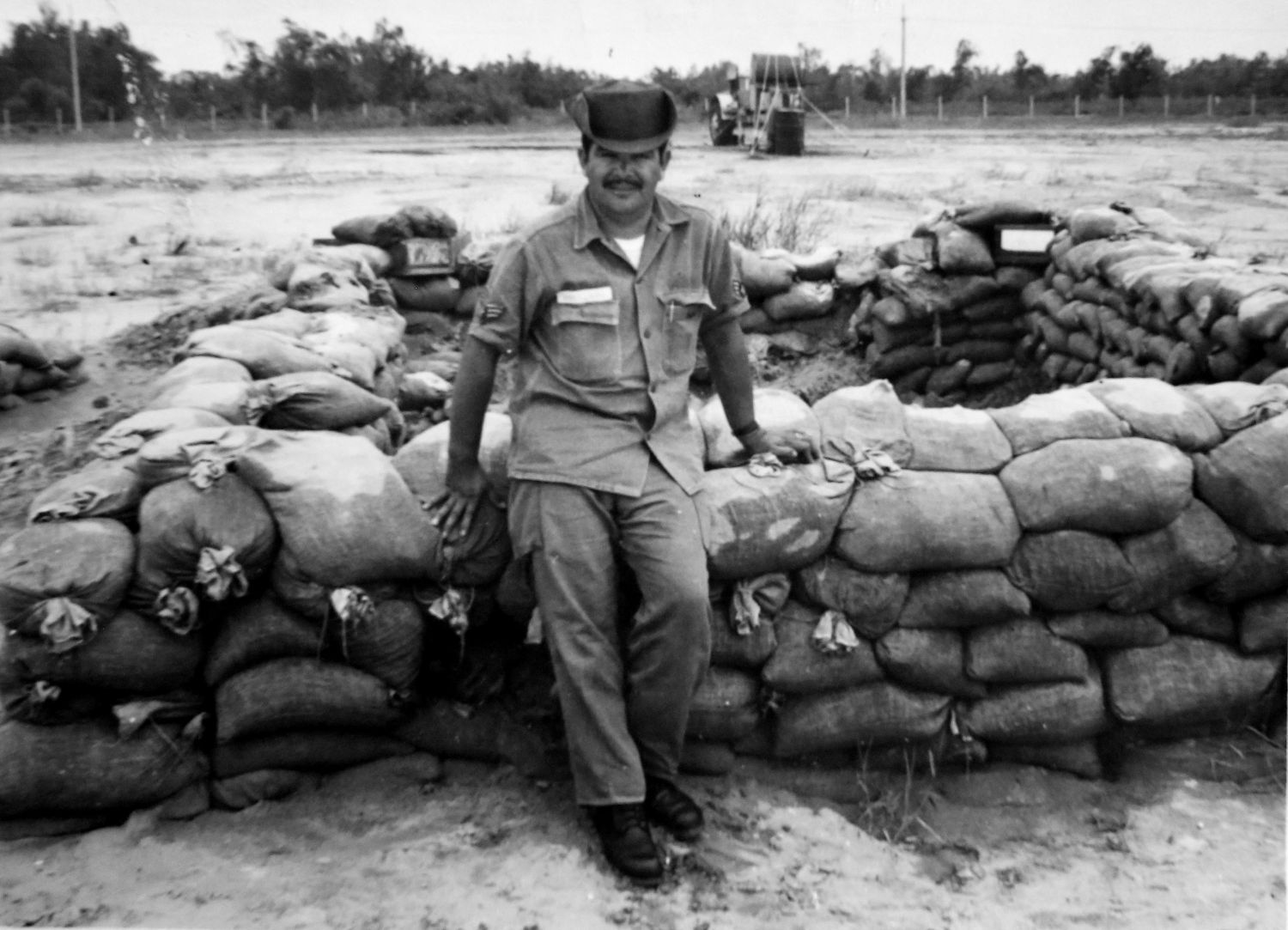

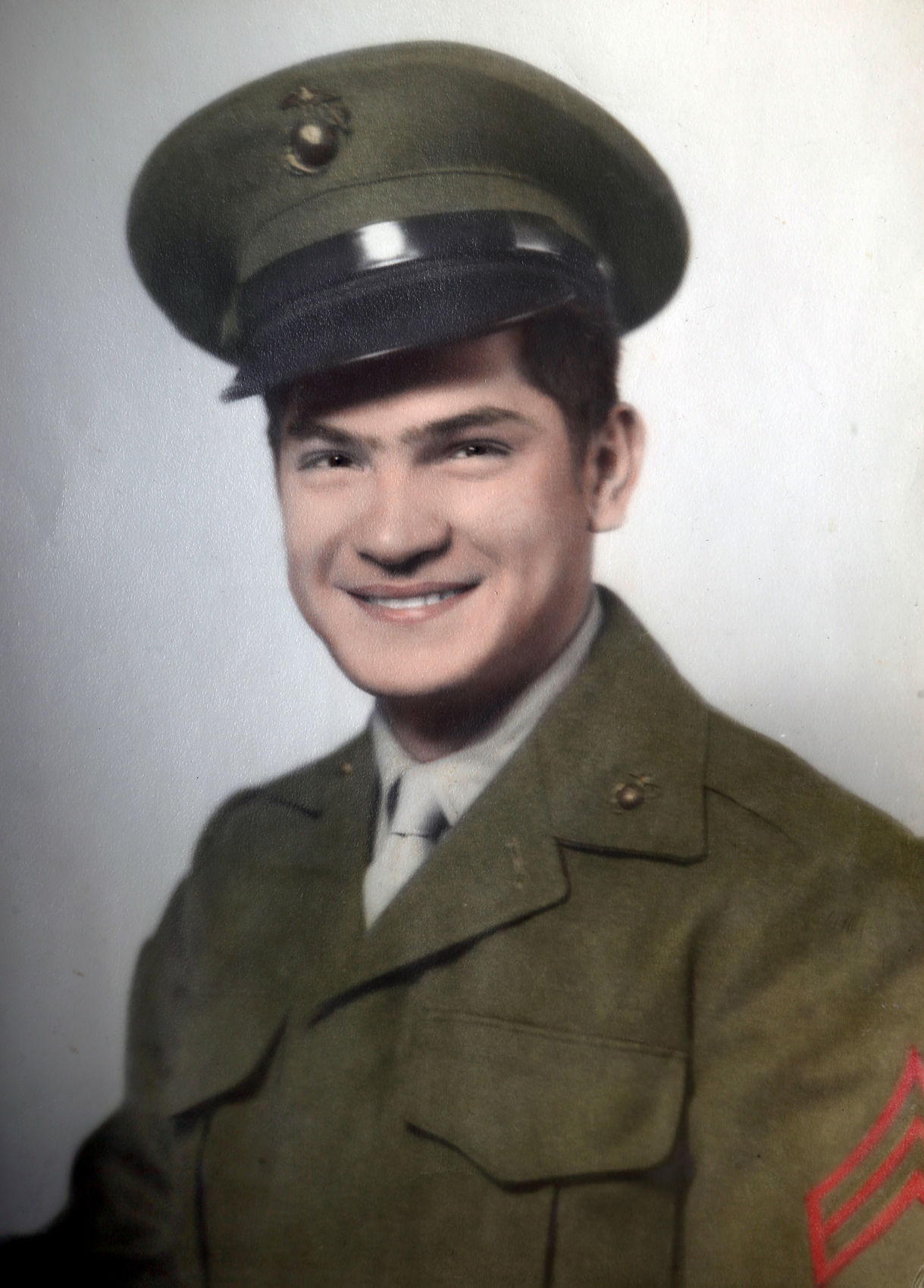

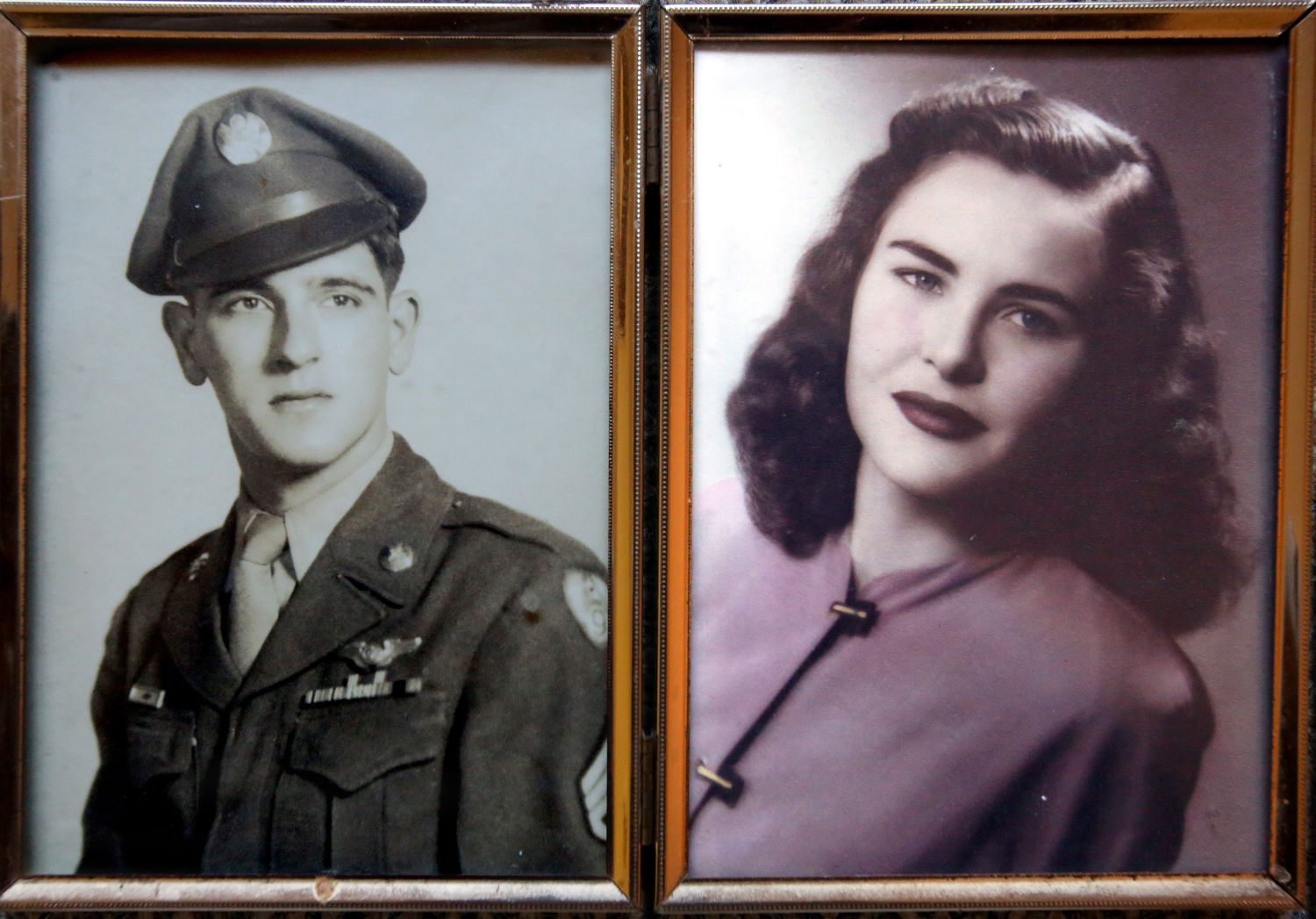

Pvt. Eddie Araiza poses for a photograph in England in his Class A uniform in 1944 during World War II.

Courtesy of Eddie AraizaIn 1929, Alfredo returned to pick up Eddie and take him to live in Cascabel with his widowed-maternal-grandfather, Miguel Gamez. It was his mother’s wish.

Miguel was living in a one-bedroom adobe house that had a dirt roof and a fireplace in the kitchen that was seldom used because the old wood-burning stove was hot enough.

“My grandfather Miguel always kept a pot of beans and a pot of coffee on the stove for anyone to have if they came by, and the screen door to the kitchen was always open,” Eddie recalls.

“He took me all over the place, on the back of his horse to check on his cattle, in his Model A Ford for trips to Benson … wherever he went, I went. My grandfather took me with him everywhere.”

“I remember my grandfather was very strict with my four uncles, Juan, Ramon, Miguel and Rafael, making them work hard on the ranch. He wanted them to be good workers, and it rubbed off on me.”

“When my grandfather Miguel died in Benson, they took his body back to Cascabel, and put him in the bed of a Model T pickup truck, and my uncles Ramon and Miguel stood on the running boards with their hats off, one on each side, all the way back to the family cemetery.”

Eddie Araiza, right, shares his memories of working at the Jelks ranch with Jaye Wells, founder of Rillito Foundation.

Courtesy of A.E. AraizaEddie’s education consisted of attending the rural Pool School, named for a nearby rancher, which was the only school in Cascabel. After his eighth-grade graduation, Eddie stopped going to school and did odd jobs.

“The reason I did not go to high school was because my family did not have the money for room and board to send me to Benson, which was about 30 miles away. Benson had the closest high school at the time,” he said.

He was 16 years old in April 1941 when he went to live and work near Vail at the X-9 Ranch, where he was a handyman and also helped the cowboys during roundups. It was here in December of that year that he learned the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, but he didn’t realize how the world would soon change.

In late 1942, still too young to serve in the military, Araiza went to live and work for Rukin Jelks, a horse breeder, at his ranch and personal racetrack on River Road, which would later become the Rillito Racetrack.

In March 1943, Araiza received his draft notice and soon joined the military.

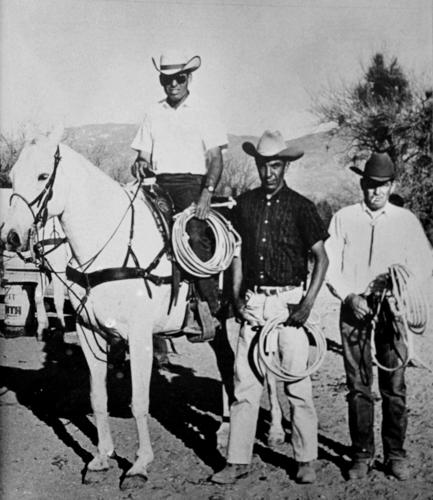

Eddie Araiza sits on his white mare, Sugar Blue, along with his friends Bobby Gracia, middle, and Rudy Tellez after winning a roping at Desert Willow Guest Ranch on East Tanque Verde Road on April 18, 1965. Araiza won both first and second place healing for Gracia (first place) and Tellez. Each were holding ropes they won as part of winnings.

Courtesy of Eddie AraizaBy then, his father and the rest of the family had moved to Tucson. His father gave him a ride to the downtown train station and unceremoniously left him there, he recalls.

Eddie Araiza was waiting for his train when he met Santiago Gallardo, who was also heading off to war.

It turned out that Santiago Gallardo, who lived in Tucson’s Barrio Hollywood, ended up not only going through training with Araiza, but that they would be in the same outfit throughout their time in the U.S. Army.

Araiza initially reported to Fort MacArthur, outside of Los Angeles, where he completed the first part of his basic training, including getting all of his shots and clothing. He continued his basic training in Fresno, California, then went to Camp Ripley in Minnesota for more training along the upper Mississippi River.

During their time at Camp Ripley, Araiza’s outfit was designated as the 1185th Military Police Company and received advanced infantry training, including bayonet training. They also were taught to drive all types of military vehicles, 4x4 trucks, jeeps, motorcycles, etc.

When winter approached, they went to Ft. Snelling, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where they were moved into three-man huts to get out of the freezing weather. From Snelling the unit went to Camp Shanks in New York, the largest Army embarkation camp used in World War II.

The unit departed for Europe on the Queen Mary in November 1943. The troops slept in hammocks during the trip. If you were on the bottom hammock, you could not even turn around when sleeping because of the bodies stacked on top of each other, Araiza said.

After disembarking from the ship, the unit traveled by train, arriving at Cottesmore, England. The Royal Air Force had an air base there, but it was used to house units of the U.S. Army, including the 1185th Military Police Company.

There, the 1185th was on duty patrolling the base, using jeeps along the perimeter and monitoring the activities at the two gates to the facility.

In the summer of 1944, after the Normandy Invasion, the 1185th flew into a captured airfield outside of Roye in northern France in C-47’s.

There they pulled guard duty at the gates to the airfield that was used by the Ninth Air Force combat units shortly after its capture. In addition to the air combat units stationed at Roye, the facility housed supplies, ammunition and fuel along with potable water and an electrical grid for communications.

He was still in Roye in May 1945 when Germany surrendered.

“We celebrated with our company commander, Lt. Paul, and we got in a weapons carrier vehicle and drove to town. There were a lot of people celebrating. The people all came out to their main plaza, where they offered us cognac to drink. They didn’t have much themselves but they did a lot of dancing. We didn’t want to take any of their food so we didn’t stay very long.”

In early August, the 1185th was loaded on to the U.S. Navy transport ship USS General J.R. Brooke, originally headed for the Philippines, but ended up being redirected to New York after the Japanese surrendered.

After getting to Chicago from New York, Araiza left by train for home in November 1945.

When he arrived at the train station in Tucson, he took a taxi to his parents’ home, which at the time was near what is now East Pima Street and North Swan Road. He reunited with his family, with many tears shed.

A couple days later, he headed downtown to get some money at the Valley National Bank, now Chase Bank, where he ran into Rukin Jelks, his former boss. After greeting him, Jelks offered him his old job back at his ranch and racetrack. Araiza replied that he didn’t know what he wanted to do.

“I didn’t want to go back to the racetrack or any ranch because they were not paying that much and the work was too hard.”

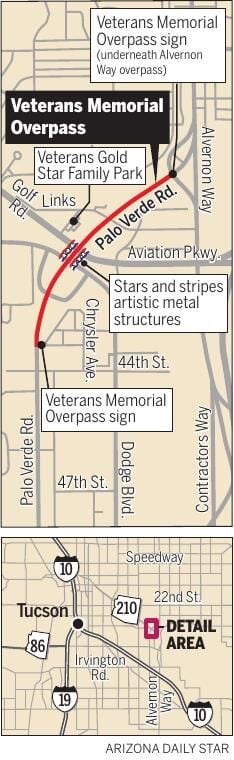

Veterans Memorial Plaza is part of the Veterans Memorial Overpass on South Palo Verde Road over the Aviation Parkway and the UPRR.

Ron Medvescek, Arizona Daily StarHis years of military service had given him the idea of what he was able to accomplish, giving him more confidence in himself and a kind of discipline he never had before.

In time, he got a job working with this uncle Rafael Gamez at Adam’s Tree Service, trimming and removing trees and doing some landscaping. In 1950, after five years of learning the trade from Adam’s, he decided to start his own tree trimming business.

The same year, Araiza married Dolores Guerra, whom he had originally met at the Blue Moon dance hall on Miracle Mile. They would have three kids, Laurita, Alfredo and Frances Deanna.

Over the years, his business, the Araiza Tree Service, thrived. By the 1970s, he owned three work vehicles, including a one-ton dump truck, a wood chipper, and a number of chain saws.

For the next 30 years, he continued his main business operation until he finally closed it down by 1980. Then for the next 19 years he worked on his own.

Even though he didn’t return to ranching work as a way of life after the war, he never ventured too far from his cowboy roots. After the war, he roped calves, then competed in team roping events as a means of recreation on weekends. He stopped competitive roping by the time he turned 75.

In 2000, he made a special trip to the family cemetery where Araiza’s ancestors have been interred since the late 1800s, near Cascabel, which was on the C-Spear Ranch property, just north of his uncle Ramon’s home.

The purpose for Araiza’s trip was to replace the white, termite-riddled cross his father and uncle Ramon had placed on the top of the ridge overlooking the cemetery years before, with a much bigger and sturdier cross of his own.

He told his son: “My dad and uncle were the first to put one up. It was my duty to put up the (new) cross. It will be your duty, or someone else’s, to put up the next one. It is our family obligation.”

- By Kristen Cook Arizona Daily Star

Editor’s Note: The Star received 265 nominations for local veterans through an online nomination form. Stories featured in the series include those veterans. Here are the names of the veterans featured in “They Served With Honor” as well as those nominated:

Stan Elbie

Sam Cohen

Thomas Coleman

John “Jack” Dyke

Mary Congdon (Mary Stirling)

Craig Sawyer

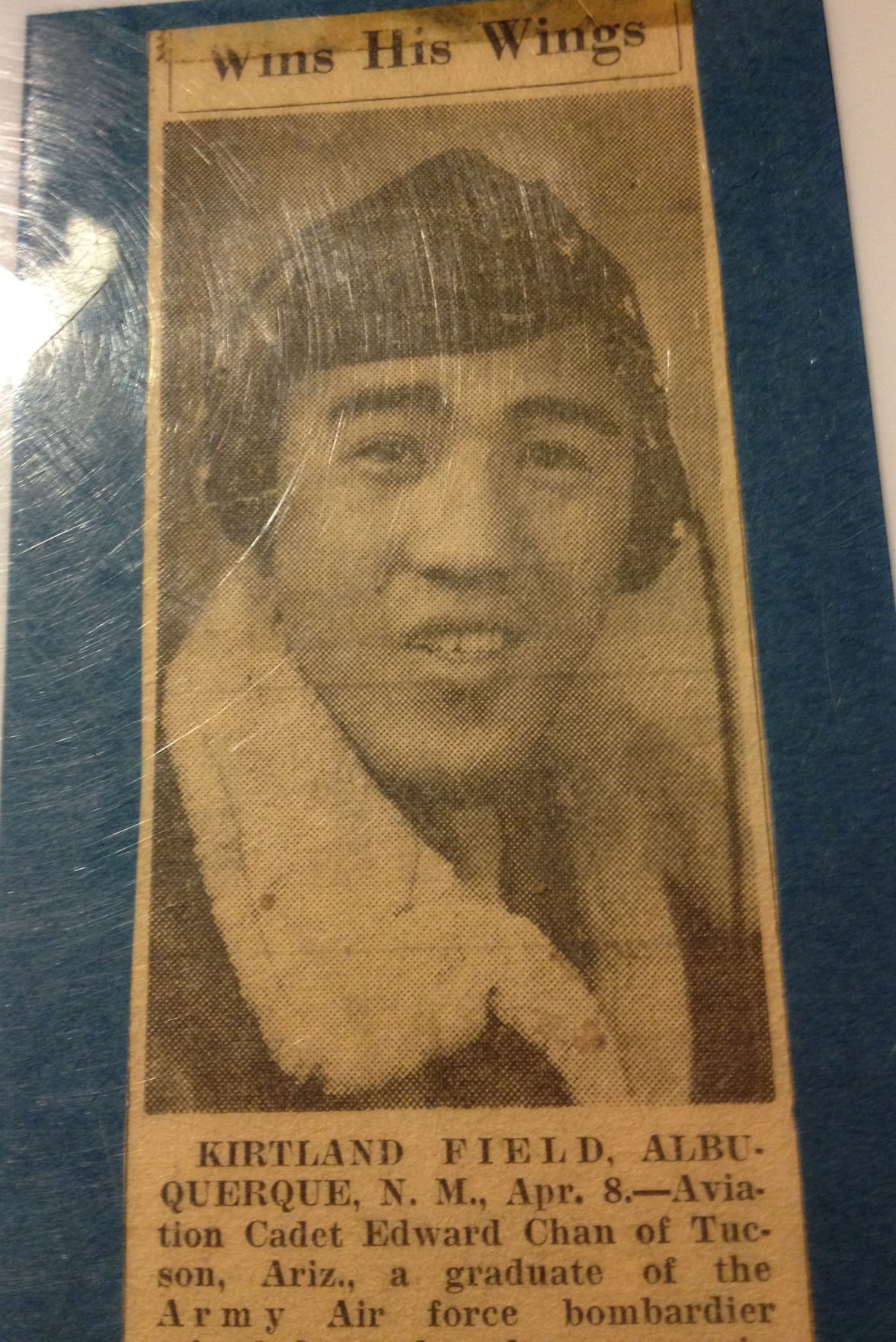

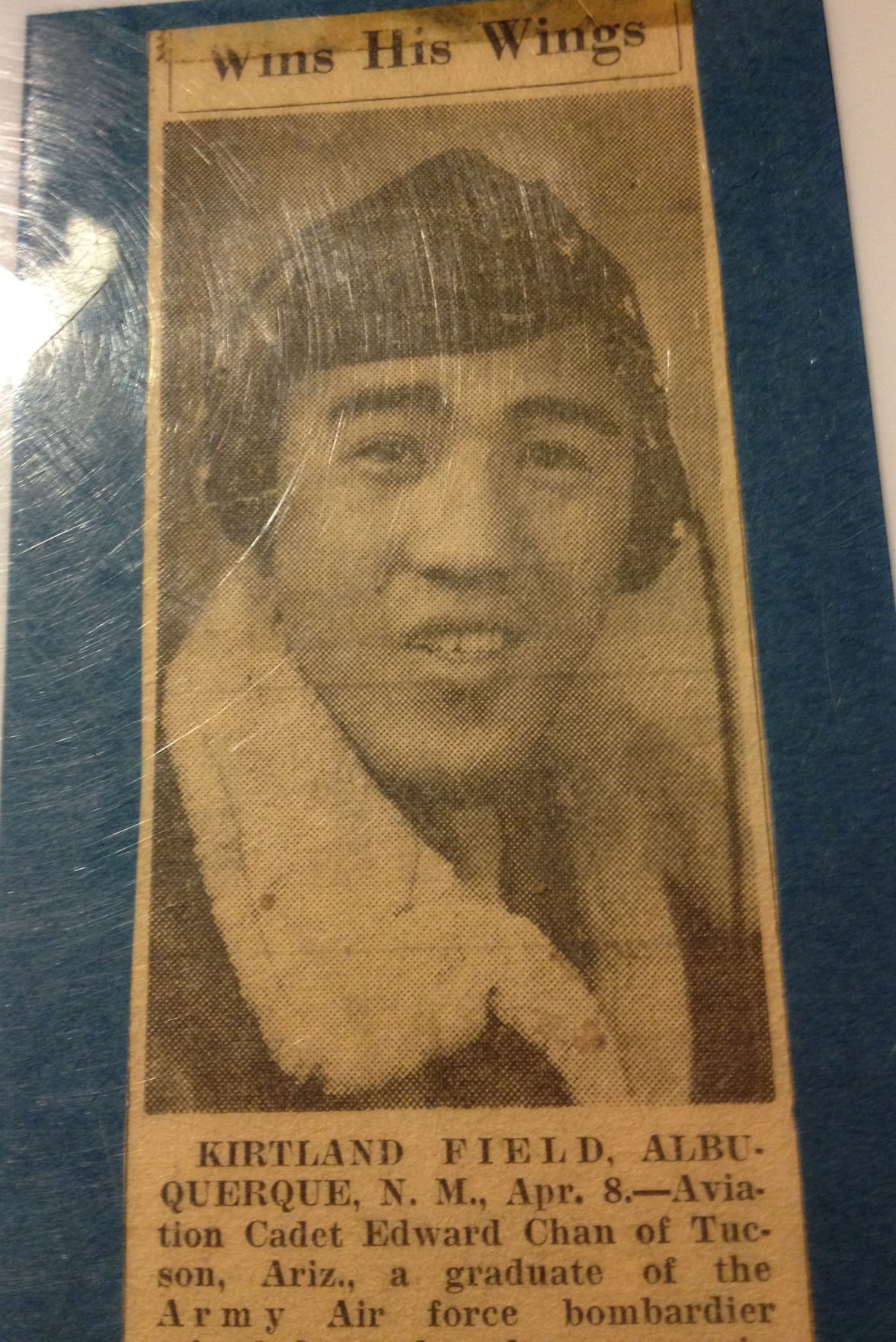

Edward Chan

Teddy DeSouza

Wayne L. Petter

Helen Anderson Glass

John Rodriguez

Juan Herraras Jaurigue

Mary Hill

Chris Guerrero

Fred Taylor

James Britt

Gerald Thomas Garrison

Roy Ludlow

Dale Hughes

Brett Rustand

Valentino Cruz

William “Bill” Peel

David Alegria

Bill Deyoe

Mel Giller

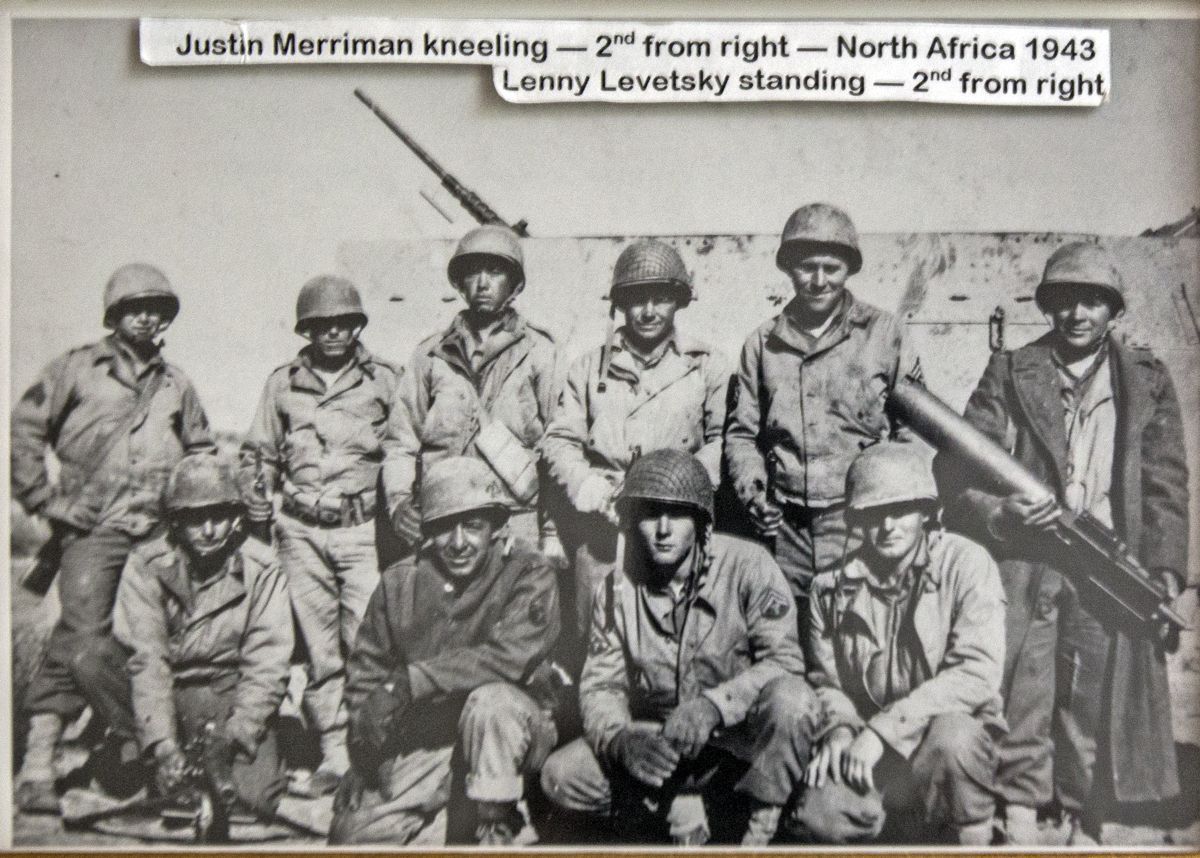

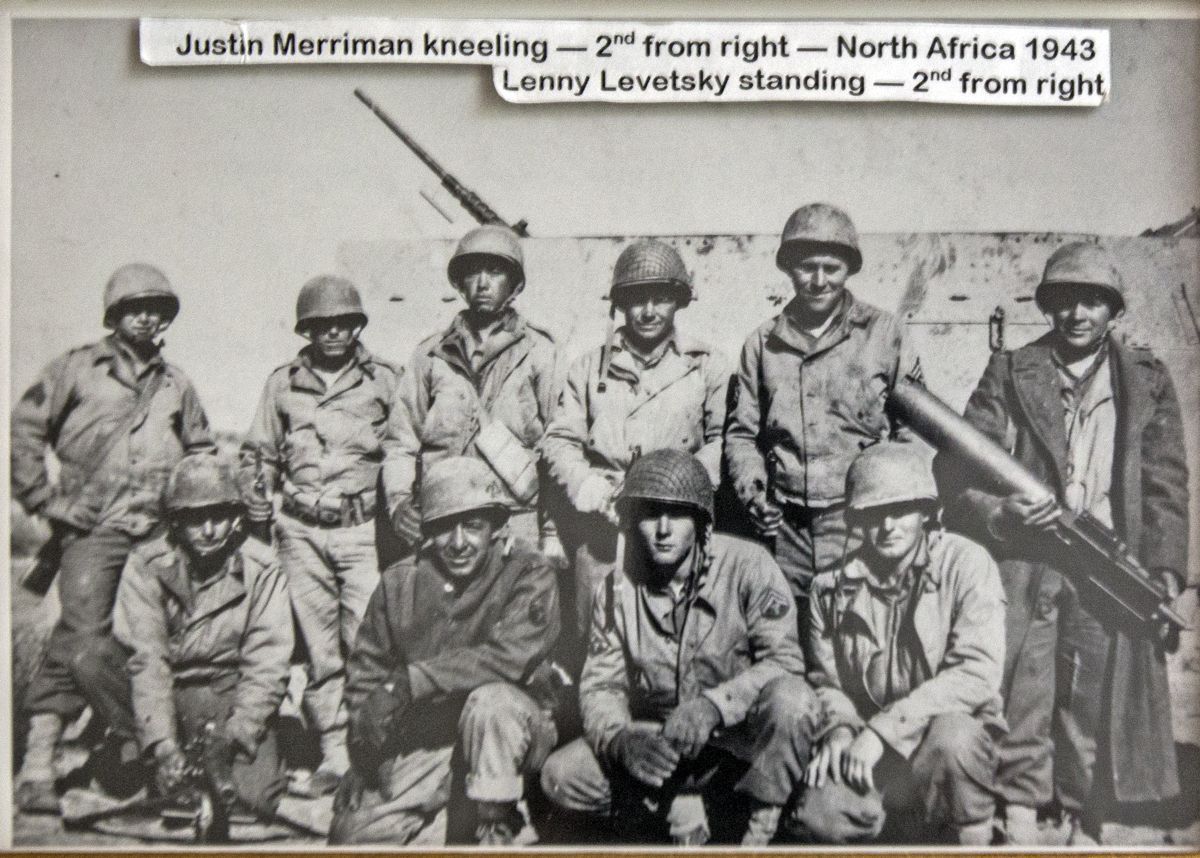

Justin Merriman

Art Schaefer

David Arellano

James Glaze

Bill LaBar

Harry Connors

Luke Burgan

Robert S. Putnam

Thomas Rankin

Daisy Gates

Lupecelia Leon

Harper Coleman

John Moore

Sam Brokenshire

John Lochert

Leo Lochert

John Lloyd Rhodes

Benjamin Arellano

Charles Wohlleb

Charles Deibel

Tom Parker

Loren Baber

Michael Matthews

Randolfo “Randy” V. Lopez

Rick Villegas

Frank Mendez

James Files

Ross Donaghay II

Jesus Zapata

Patricia Smith

Jeanne Rogers

Al “Harpo” Celaya

Cliff Wade

Rafael Samay

Melvin Giller

Mary Jane Hill

Nelda Barnes

Gopal Khalsa

Alan Lurie

Robert Barnett

Robert Spencer

Edward Kulik

Curtis Layton

Lyman Threet

Marion “Smitty” Smith

Melvin Morgan

Carl M. Shumway

Charles McClain

George McGee

Earl Liston

Samuel Duncan

Richard Love

Bruce Seymour

John W. Auvenshine

Elmer Nicholson

Max Warner

Myers B. Rosenbloom

Ebb Daughtery

Richard H Brown

John B. Janicek

Byron Burns

William Mesa

Robert B. Johnson

Gregory Gomez

Jeffrey Eighmy

Brendan Phibbs

Harold Koobs

John Fedor

David Morrison Hardy Jr.

Edward V. Lovio

Milton Dietz

Henry Burke

Eugene Metcalfe

Eugene Scott

Harry Laughman

Roy Meyer

Gerry Meyer

Aaron P. Raita

Mac Edward McQuillen

Glen Meunier

Michael Johnston

Steve Pockuba

Glen Hughes

Arthur R. Voss

Mary Smith

Leonard Kraft

George J. Popovich

John Chastain

Charlie Ruggles

Steve Martinez

Ken Laue

Raymond Stroehlein

Gwendolyn Clymer Niemi

Joe Ford

Herbert Mendoza

Onofre Tafoya

David Stone

George Romontio

Gilbert Romero

Donald Beery

Tom Ketchum

John D. Kaperka

Richard Bushong

David Bertagnoli

John W. “Johnny” Gibson

Joe Ladensack

Edward H. Nelson

Colonel Robert B. Beaumont

Samuel C. Pacheco

Paul Cartter

Debbie Seager

Robert Miller

Lawrence Casper

Thomas Duddleston Sr.

William Reede

John Wickham

Jesse DeVaney

Thomas Drew

Andy Anzanos

Jose E. Vega

Kenneth Eckle

Norman G. Benson

Gordon Thorstad

David G. Lucas

Larry Brimm

James Redmond

Joseph Nichols

Antonio “Tony” Valdez

Frank Soto

Robert Sexton, M.D.

Gene Forsyther

Robert De More

Glenn Perry

Al Stockellburg

Joseph Dogoli

Chris Christenson

Wynn Freedman

Thomas Storey

Ray Alfred Fischella

William J. Orscher

Edgar Harrell

Homer “Ed” Adams

Dan Gipple

Anthony K. Van Reusen

Charles Lagneaux

Michael Lazares

Dick Palmer

Donald Gibbons

Richard Pfaff

Clarence Burgan

Don Dingee

Carl Beck

Walter Ram

James R. Huerta

Sam Duncan

Charles Wohlleb

Henry A. Stewart

Don Childs

Clarke Duncan

Ralph A. Grant

Richard Edwards

David Crocker

Harry R. Erickson

Tracy Sparby

Sheldon Coudray

Diana Thacker

Fred W. Astroth

Ken Collins

Hjordis Sherry

Gary Blomstrom

Paul R. Gale

Lance Gillingham

Alexander R. Martinez

Doris E. Manning

Charles Gutekunst

Edward Chan

Harold Dees

Benjamin Ricardo

Solorzano Vivar

Nathan Shapiro

James McDowell

Jack P. Marshall

Ron Sable

Mike Rosenbloom

William Greenberg

Donald Fitzgerald

W.B. Punt

Earnest Parks

Augusto Cesar Gomez Sandino

Don Goldner

Jim Wagner

William Ersthaler

Patrick Franco

Louis Iannacone

Jayme Berg

William “Bill” Alviar

Frank Zunno

Virginia Baber

Roger Johnson

Bernard Reinhart

Donald W. Manke

Robert Ashby

Cloud Funaro

Estella Curry

Calvin D. Pigman

Henry G. Johnson

Jack U. Goodhart

Maurice Storch

Joe Bailey

Thomas Hunt

Leo Silverstein

Donald N. Olson

James Purdue

Ken Weihl

David Morales

Earnest Cotton

Donald Collins

Dennis G. Dierking

Donald Shepperd

Chuck Heathman

James W. Waln

Raymond Romero

Tim Clark

Rodolfo Bejarano

Javier Ledesma

Earl Scott

- By Kristen Cook Arizona Daily Star

Johnny Thompson considers himself lucky.

The 68-year-old suffers blackouts and his short-term memory is shot.

Double vision plagues him. Sometimes he struggles to speak. “I lose words real bad,” he says.

On a good day, he can walk with a slight limp. On a bad one, he can’t take a step without the safety and security of a walker.

He served three tours of duty in Vietnam and each earned him a Purple Heart. He still carries a steel bullet — an armor-piercing round — in a spot so precariously close to the left vertebral artery and his spine that a doctor warned him to never be more than 40 minutes from a hospital.

This guy? Lucky?

“I still feel like the most blessed person in the world,” says Thompson.

Because, of course, he came home.

The veteran counts, among his blessings, a strong faith in God, three children — who all live within 15 minutes of his Marana home — nine grandchildren and his wife of 47 years, Gay. He might pick up his cellphone and not remember whom he wanted to call, but he can describe the day he first laid eyes on her, wearing a polka-dot dress, at a Texas church gathering when they were teenagers.

|

You’d never know about Thompson’s problems just by looking at him. He’s friendly, gracious and has a mischievous sense of humor.

“He’s dedicated, he’s compassionate — he’s just a good man,” says Andrew Bowers, an Army veteran who met Thompson through their church. “His heart shines through. He’s got a smile on his face all the time. He’s positive, he’s optimistic. Those ailments don’t hold him back. He has his bad days guaranteed — he doesn’t let it stop him.”

He did. Once.

At the darkest time of his life, Thompson admits he was suicidal, so depressed he could only sit on the couch. His body was wracked with seizures, and his memory and speech kept failing him.

A mistaken Alzheimer’s diagnosis at age 41 had him living his life in one-to-two-year increments. Now doctors know traumatic brain injury, coupled with the side effects of medications, caused his problems.

Despite his injuries, Thompson spent nearly three decades in the Army, assigned to several different units including Special Forces, and rose to the rank of chief warrant officer 4. Even in retirement, he’s dedicated to the military — and more specifically, those who served in it.

People come to Thompson, asking him to find out about their dads or their uncles or their grandfathers who have died. They want him to fill in the blanks because veterans, back in the day, just didn’t talk about what happened during war.

That uncommunicativeness coupled with a 1973 fire at the U.S. National Personnel Records Center in a Missouri suburb that wiped out millions of official military personnel records, make it even harder for relatives to research backgrounds.

The Thompsons scour the Internet, uncovering what they can. When they discover a veteran earned a medal, Johnny will track down a replacement for the family. He types up histories while Gay has even re-created embroidered naval ship patches.

|

The two also curate traveling military history displays that have been displayed across the state at conventions and churches.

Some of Thompson’s Vietnam War mementos are on display now in Tempe (see box at upper right). Thompson got the idea when he took some keepsakes to the local veterans hospital about four years ago. He watched fellow patients’ eyes light up as he passed around a disarmed flechette warhead.

He’s managed to acquire so much stuff that three of the six bedrooms in Thompson’s house are devoted to military memorabilia. Even the one dedicated to the grandkids’ sleepovers is overrun with documents and uniforms.

Down the hall from the upstairs bedrooms, framed rubbings from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall decorate a sitting room.

Thompson chokes up when he points out the names belonging to two soldiers in his unit.

“The one thing you can’t stand about war is the people you can’t save,” he says, softly. “It’s the ones you lose — they’re the strongest memories you have.”

Thompson’s own medals and ribbons fill a shadow box hanging on the wall, but he won’t talk about those.

“A lot of people don’t get anything when they should have,” he says.

The son of an Army Air Corps experimental test pilot who helped design helicopters, Thompson was just 16 when he enlisted. A doctor realized he was underage and blew the whistle on him. Undaunted, Thompson enlisted again the next year.

After he graduated from flight school, and even though he had a wife and young kids, Thompson volunteered to go to Vietnam.

“I could rescue people,” he says. “I knew I could help people.”

The master helicopter pilot ended up serving three tours of duty in Vietnam and though the United States’ role was controversial, Thompson had and still has no qualms.

|

“Free the oppressed. I believe that with all my heart.”

His third and final tour in Vietnam was the worst.

“We went over with 83, 84 guys,” he says. “Only 22 returned home.”

Thompson himself barely made it.

He remembers the mission he flew on May 19, 1971, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday and two days after his own. It was one he’d flown solo many times before, but on this occasion, it was in a new Huey helicopter — and with a co-pilot. Having Capt. Bob Jorgensen along with him that day saved his life.

“I was down low, looking for footprints,” Thompson recalls. He was hanging out the door of the chopper, scouting for signs of the enemy when more than 150 bullets peppered the helicopter while mines exploded from below.

“I was just shooting blood out of my neck,” Thompson says. “When I got hit, I lost control of the Huey. It was straight up in the air.”

Two bullets sliced through Thompson’s throat, hitting vocal cords and his larynx and almost completely splitting a vertebrae. Discs in his back were crushed from the explosions beneath the chopper.

Thompson passed through six or seven hospitals as he made his way back home. “Everywhere I went, everyone said, ‘How are you still alive?’”

Thompson does what he can to make every minute count, which is why he spends so much time and effort on researching fellow veterans’ military histories.

Even with Gay’s help, it’s painstaking work. “It takes us a month what other people could do in two days.”

Thompson might spend four or five hours researching and writing what he learns. But the next day, that knowledge is lost. Completely wiped from his memory. He has to read over everything and reacquaint himself with the previous day’s work.

It’s frustrating, yes, Thompson admits. But it doesn’t deter him one bit.

“I’m going to keep going until I don’t know I’m doing it any more.”

He was on the path to becoming a teacher, but the military draft in 1948 changed Loren Baber’s life.

But instead of returning to teaching 40 years after he got back from the Korean War, Baber, 85, took on a new endeavor when he and his wife joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary.

After graduating from high school in Nebraska in 1948, he enrolled in Wayne State Teachers’ College, hoping to be a coach.

As he was preparing to leave for school, his plans changed on July 20, when President Truman enacted a peacetime draft.

“I was a college boy, which made me Class 1-A. I was to be called up in 30 days,” he said. Baber explained that in those days, “farm boys” were classified as 4-F and were often the last to go, as they needed to stay home and tend to the family business.

As soon as he knew he was getting called up, he went to the recruiting office so he could chose his branch, as opposed to be assigned to one.

|

The Air Force quota was full, so he joined the Army at 18 years old.

He qualified for Officer Candidate School and headed to Kansas for his training.

“Because of the draft, they had more people than beds so I had to wait a little while to get in,” he said. He left candidate school after having completed the Infantry Advanced Leader Course.

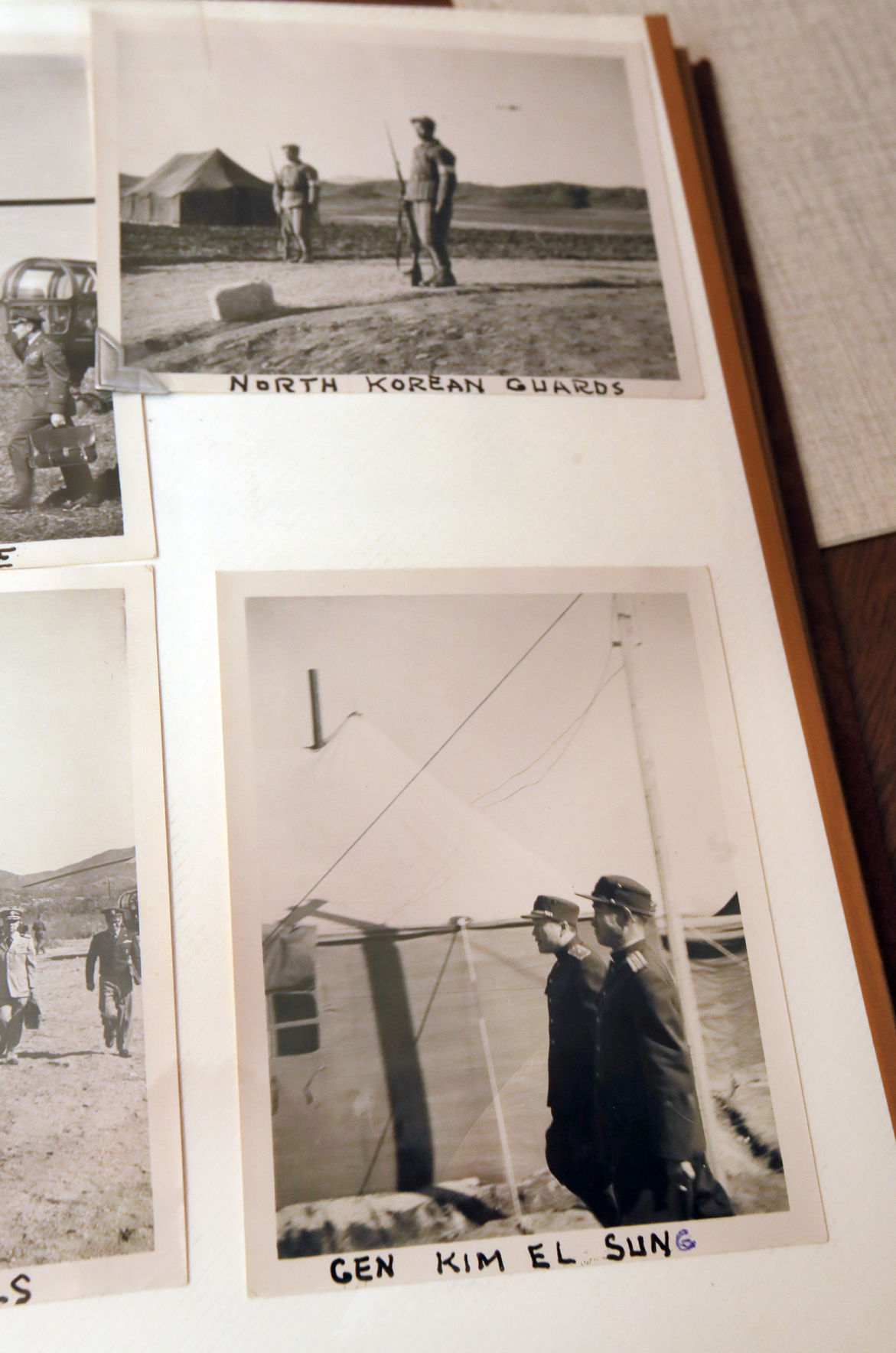

In June 1950, the Korean War began and he received orders to go to California, which meant he was headed to Korea.

He arrived in November and spent Christmas Eve on a ship off the coast of Incheon, near Seoul getting ready to go ashore.

“The captain came over the loudspeaker and called our craft back,” Baber said. “Seoul had fallen.”

He was discharged in 1952 and set up shop in Iowa as a photographer.

In 1968, he married Virginia and purchased an insurance business before they started a family.

Fifteen years later, after everyone was grown they signed onto the Coast Guard Auxiliary using their own boat for over a decade for search-and-rescue work and to patrol.

“It became a career we really loved,” he said.

|

They spent about a year qualifying to use their own boat, and soon they were cruising the California Delta as an official government vessel.

“Once we signed on for our weekend patrols, the boat became the property of the Coast Guard and we were at their beck and call,” said Virginia.

They spent their weekends on their 32-foot boat with two crew members helping stranded boaters and assisting with search-and-rescue operations.

“I was brought up doing service for others,” Virginia, 73, said. “My mother always told me, ‘you have two hands; one is to help yourself, one is to help someone else.’”

They retired from the Coast Guard Auxiliary in 1995 and moved to Tucson, selling the boat before they left.

Although Loren speaks excitedly of his time in the Army and they both miss their days of patrolling the water, they’ve both taken on different types of volunteer work, continuing to help others as they’ve done their whole lives.

- By Patrick McNamara Arizona Daily Star

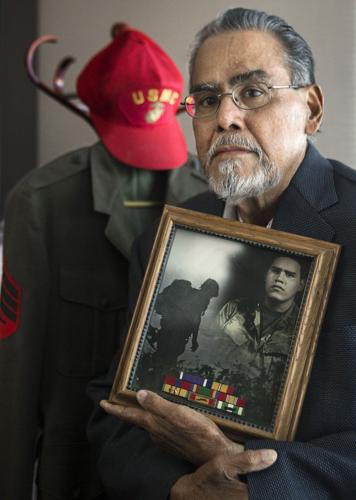

Vietnam is frequently on Tucson attorney Randolfo “Randy” Lopez’s mind.

How couldn’t it be? Having dropped out of high school, he spent some of his most formative years there as a Marine fighting for his country.

“I was just two weeks into my 18th birthday and I’m in Vietnam,” Lopez said.

Even now, certain sights, sounds, smells and weather conditions can spark those memories.

The humidity, in particular, makes Lopez think of Vietnam.

When he starts to talk about his experiences, you understand why.

“When you’re in battle, your adrenaline flows and you sweat,” Lopez said. “And the first thing you remember is how thirsty you are.”

That’s what happened to Lopez and his Marine compatriots in early 1969 a part of a major offensive called Operation Dewey Canyon.

U.S. forces were positioned near the DMV in an effort to keep the flow of troops and materiel from flooding into the south.

After more than 50 days of fighting, the operation was considered a tactical victory for the United States. But the costs were immense. More than 130 U.S. Marines were killed, and nearly 1,000 were injured.

“I still have memories of this,” Lopez said. “That was a battle scene of battle scenes.”

|

He remembers rushing down steep canyon walls with other Marines to aid another company that had been ambushed. Dead and wounded Marines and North Vietnamese forces lay across the canyon floor.

“What we had to do was get the the dead and injured out,” he said.

Lopez said he helped drag a dead Marine back up the steep slope, inch by inch, pulling the fallen man by the belt, grabbing onto tree branches and roots and anything he could find for leverage.

It took nearly 12 hours to reach to top of the mountain, fallen colleague in tow.

After two tours in the war, Lopez returned to Tucson and started working and going to school.

He earned a GED while still in the Marines and used his GI Bill benefits to help pay the costs of tuition at the University of Arizona. Even after graduating, Lopez said he wasn’t sure what he would do.

One day, while working as an auto mechanic, he met someone who would change his life.

|

“I met an attorney who came in the shop,” Lopez said. They talked, and the man suggested Lopez consider law school.

That man was Armand Salese, a Tucson lawyer who fought for civil rights and was known for taking on cases representing the underdog. He died in 2013.

Now 65, Lopez has been practicing law since 1985.

For his final law school project, Lopez chose a topic he knew well.

He wrote about post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam vets as a claim for insanity defenses.

“It was a labor of love for me, being a Vietnam veteran and seeing how PTSD had affected people,” Lopez said.

- By Ethan McSweeney For the Arizona Daily Star

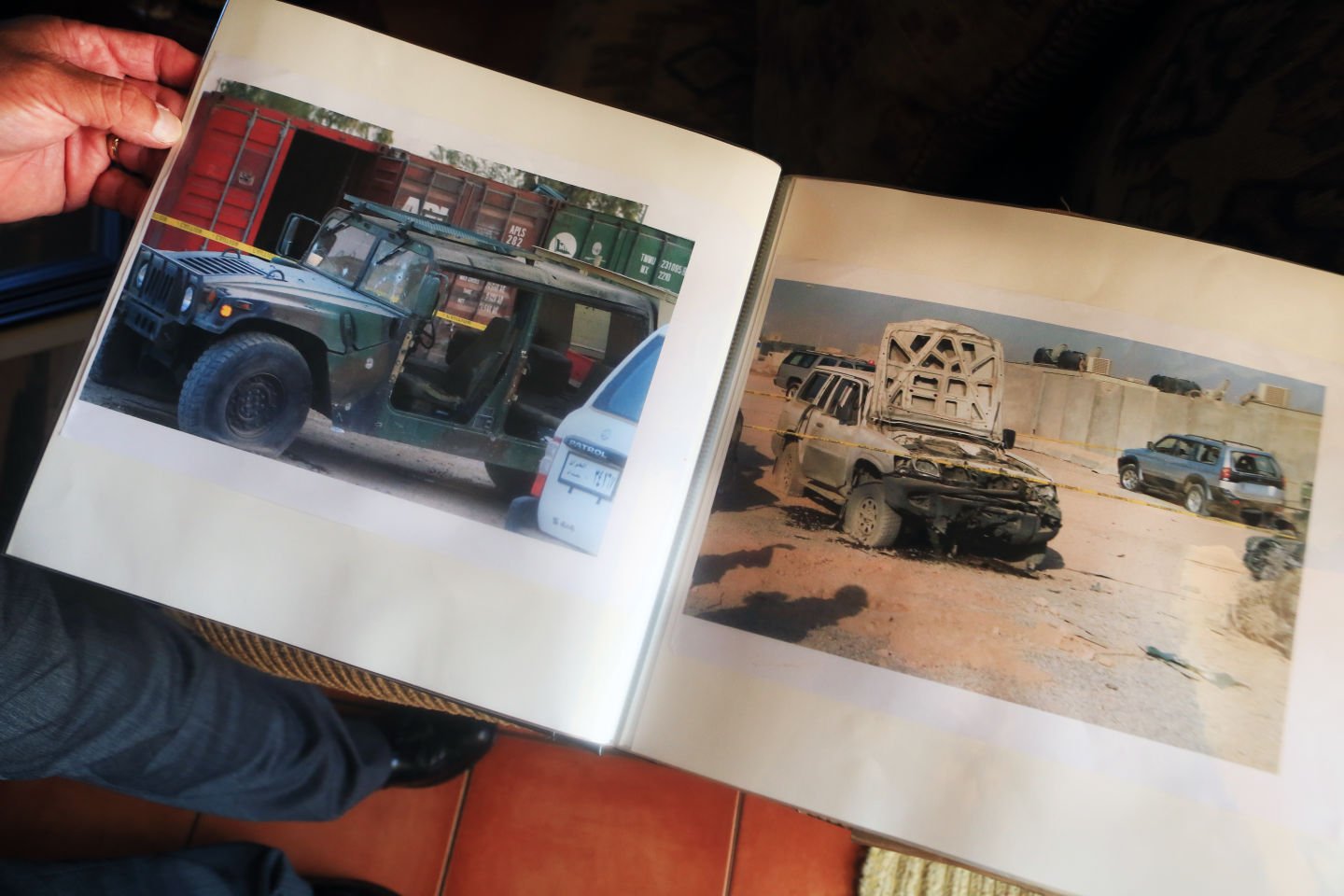

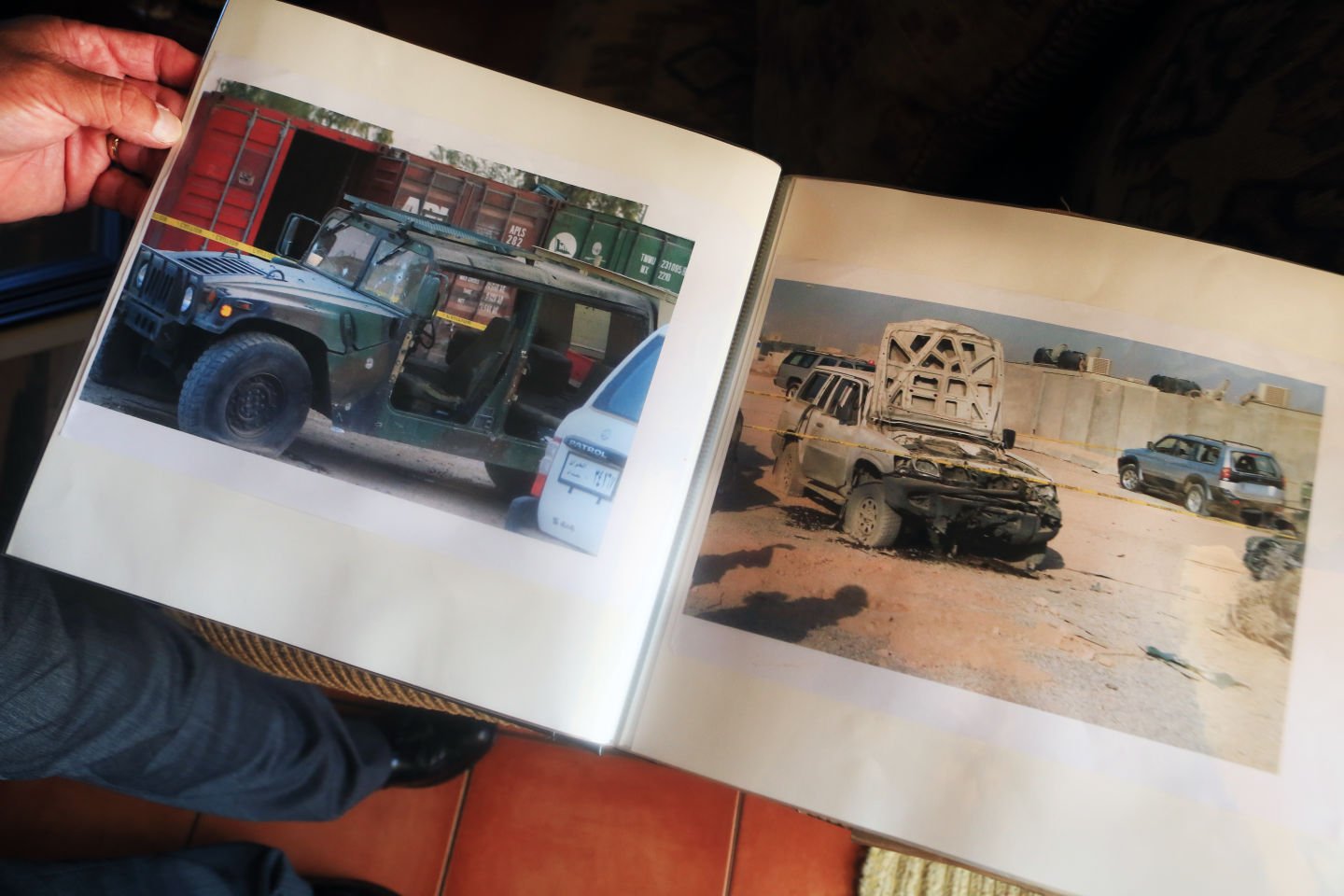

Rick Villegas stood outside in the August heat on a base north of Baghdad when things began exploding around him.

Four mortar rounds fell near Villegas, destroying vehicles and blowing out windows. His heart racing, the Army National Guardsman ran for cover.

“You don’t think of it until after it happens, how scary it was,” Villegas, 65, said. “It just wasn’t my time to die.”

Attacks from insurgents weren’t uncommon on Villegas’ base in 2004 Iraq, he said, but it was a close call for him.

“We were getting hit with rockets and mortars constantly and people got killed,” he said. “Unfortunately, that’s what happens in combat.”

The Tucson native joined the Army National Guard in 1971 at the age of 20, following in the footsteps of his father, who served in the Guard and fought during World War II.

|

After serving in the National Guard for more than three decades without being deployed to a combat zone, Villegas learned over the phone in late 2003 that he was going to be sent to Iraq. An officer told him that he was needed for his background in the military police.

Fifty-three years old when he went to Iraq, Villegas was much older than most of the soldiers he served alongside. While he served in a logistical role in the war, the position wasn’t easy for him.

“Iraq was very hard at my age, but I felt good that I was a soldier on the ground like everybody else,” he said.

|

He was stationed at a base in the city of Balad, about 50 miles north of Baghdad, where he was in charge of tents and housing for Marines and soldiers stationed on the base, ensuring they all had a place to sleep.

Driving through Baghdad and being on a base that was frequently attacked, his commander told him to stay alert, “keeping his stinger out” like a scorpion, Villegas said.

Back home in Tucson, his wife, Gloria Villegas, worried about him. “It was stressful, because on the news they had all the reports of bombings over there,” she said.

Gloria Villegas said she would have to turn off the news when reports from Iraq came in. Villegas would send her emails and calls after attacks and other major events to assure her he was OK.

|

He came home from Iraq in late 2004 and retired from the National Guard in October 2006.

“Adjusting back to our world was hard for him and it was hard for me because I didn’t know what to do,” Gloria Villegas said.

Villegas battled health issues since returning, including surgery complications and cancer. He’s been going to back and forth from the VA hospital for appointments and treatments.

Villegas said, though, that he’s happy he got the chance to serve his country in Iraq and serve in the National Guard for more than 35 years.

“Looking at all these years of service I put in,” he said, “I was just proud to be an American soldier.”

- By David J. Del Grande For the Arizona Daily Star

Attending annual reunions has helped Army veteran Frank Mendez learn more about the POWs he helped rescue from a Japanese internment camp as well as cope with his memories.

During the daring rescue at the University of Santo Tomas, Mendez’s small detachment went behind enemy lines in order to save American prisoners facing execution, he said. And considering the odds, Mendez and many others believed they would not get out alive.

“I considered it to be a suicide mission because we were a small force,” Mendez said. “And I wasn’t the only one; several of the boys thought that, too.”

Like many soldiers, Mendez, 92, has no regrets and remains humble about his time in the service.

Although Mendez was frightened, that assignment was business as usual, he says now with a warm laugh. “It was just another mission.”

Mendez was born and raised in Tucson, and with the nation slowly recovering from the Great Depression, he enlisted in the Army on Aug. 5, 1940, for financial reasons.

“Times were pretty hard and I came from a big family,” he said.

So before the U.S. entered WWII, Mendez became a soldier and persuaded a neighborhood friend to enlist with him. The two men fought side by side throughout the war and were both wounded during a battle on the streets of Manila.

He served in the 1st Cavalry Division and went through basic training at Fort Bliss, in El Paso.

Upon deployment, Mendez’s trip took about 30 days because the single-gun ship had to zigzag its way through warring seas without an escort.

The first stop was Australia, then New Guinea and eventually many hard fought battles throughout multiple Philippine cities, Mendez said.

When he heard a rescue mission in Manila was next, Mendez knew his small troop was attacking about 20,000 Japanese troops head-on.

And if they were met with any type of a counterattack, both the cavalry and prisoners would have died, he said.

Even though the troops shared their rations with the POWs, Mendez didn’t consider himself worthy of praise. And Mendez explained to the young prisoners the longstanding sacrifice of their family members was the singular heroic act.

“We’re not the heroes, your parents were,” Mendez said, “They were doing without to keep you healthy.”

One of the POWs was Liz Irvine, who wrote about her experience in “Surviving the Rising Sun.” Mendez has remained in contact with Irvine since that evening, he said.

Laura Mendez, Frank’s wife of 68 years, learns a lot about his time in the service while attending the annual reunions, she said.

“He doesn’t talk much about when he was in action,” she said.

But the memory of seeing emaciated civilians scarred him, she said. Although Frank Mendez is always impressed by the praise he receives, recalling that time still hurts, she added.

The annual gatherings are pleasant, inviting experiences, Laura Mendez added, but time and again her husband insists the survivors themselves deserve all the credit.

“It’s very warm, very nice and the people are very grateful to him,” she said. “They call him a hero, but he’s not happy with that. He calls them the heroes.”

It was July 1968 and Jim Files — an airborne and scuba-qualified reconnaissance Marine — was assigned with fellow Marines to guard a bridge at Cam Lo, Vietnam.

“We would scuba under the bridge,” recalled Files, 69, of Tucson. “We called ourselves the Parafrog Devil Dogs.”

That name, and the pride behind it, reflects the strong, enduring esprit de corps of Files and his comrades in arms.

His path to the Marine Corps and Vietnam might be traced to his days at the University of Illinois, where he studied after his youth and high school years in Barnhill, Illinois.

“The Vietnam War was escalating, and there was a lot of debate about it” among students at the university, Files said. “I was usually the one saying that yes, we belong in Vietnam. We must stop the aggression of communism.”

|

Those beliefs eventually led to action.

“At the end of my second year at the university, I enlisted in the Marine Corps” in 1966, Files said.

He completed boot camp, infantry training and radio operators school.

“I went to jump school (for parachute training) at Fort Benning, and I also did amphibious recon training,” Files said.

He went to Vietnam at the end of March 1968.

“Our company was doing four-man patrols,” said Files, who served with the Third Force Recon Company. “We went into the bush for a week at a time — scouting for enemy troops and supply dumps.”

Later, after guarding the bridge at Cam Lo with his fellow Parafrog Devil Dogs, it became his role to “keep in communication with recon teams in the bush.”

It sometimes involved going into combat in support of a recon team and engaging in firefights with the enemy.

He survived those firefights, but other experiences left a mark. One of those involved a close friend.

|

“We had a plan to someday open a combination bookstore, bar and restaurant,” Files said. “Then he got killed.”

Files received an honorable discharge in 1969, returned to the United States, continued his education, and eventually settled into a long career in journalism that took him from Illinois to Colorado, Guam and Arizona.

He met his wife, Meg, in a writing class in 1970, and they were married in 1971.

Meg Files, who is the English and journalism department chair at Pima Community College, nominated her husband for recognition in this series, saying “his experience in Vietnam was influential in shaping his professional and personal life.”

“He had some unique experiences in Vietnam,” she noted. “He said, ‘If you’ve grown up reading certain books, watching certain movies, hearing certain stories, you need the opportunity to know you are brave.’ He is one of the bravest people I know.”

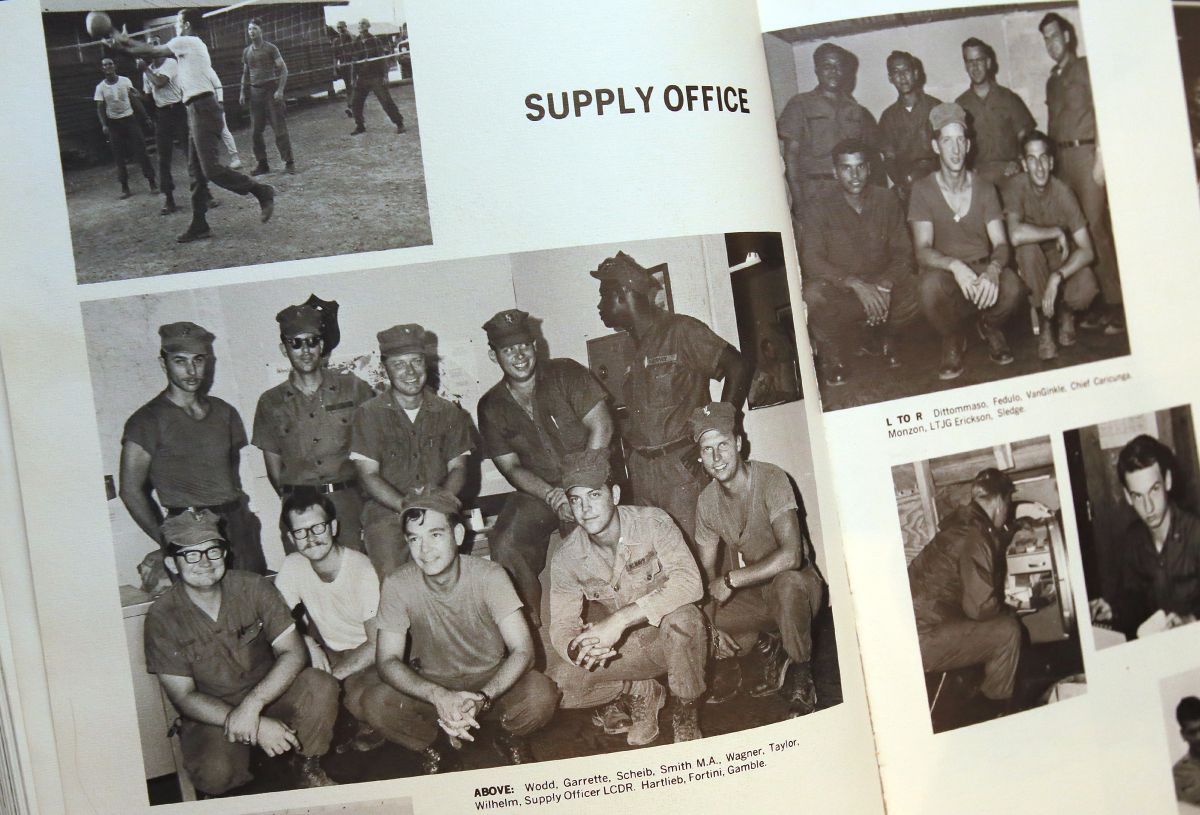

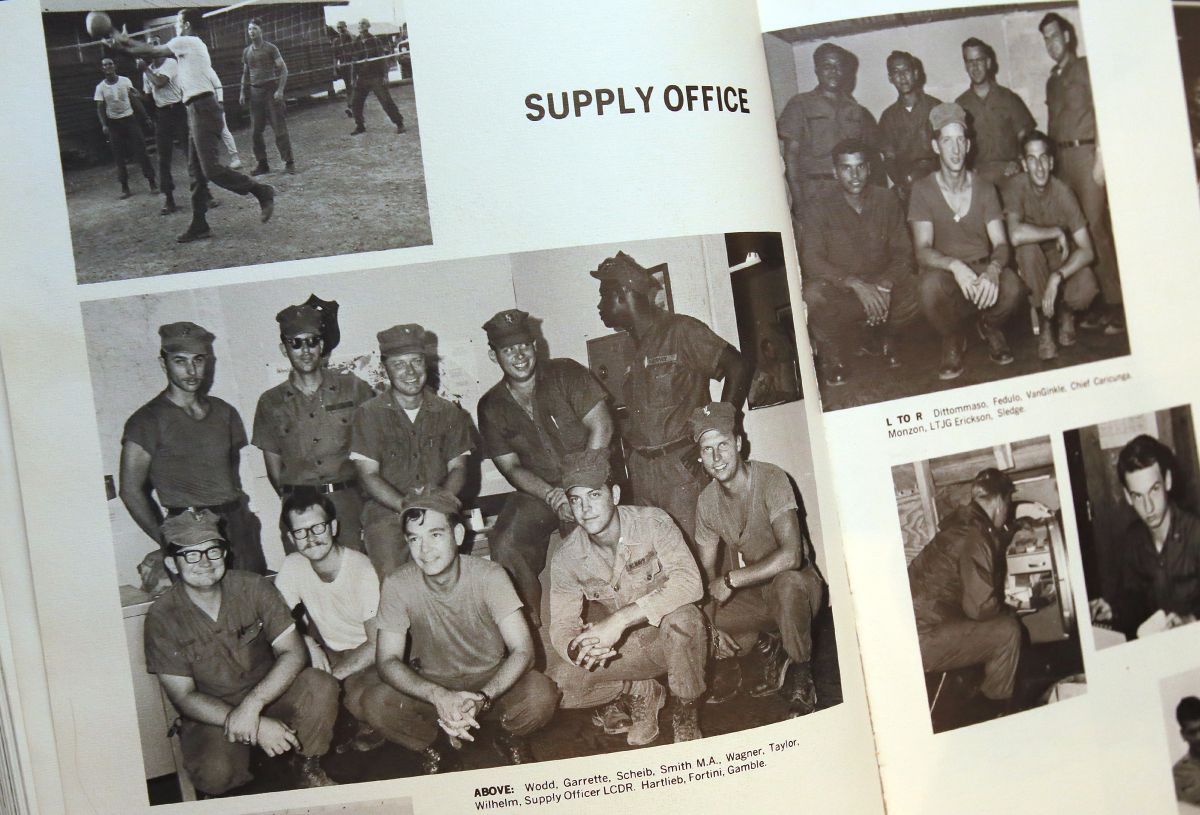

While serving in Vietnam in 1969, Michael Matthews never took his Navy-issued .45-calilber pistol out of its original packaging.

Instead, he checked the pistol into his civilian luggage and used the holster to carry a knife, fork, spoon, and a pair of sunglasses.

“I wanted to serve my country, but I didn’t want to kill anybody,” said Matthews, 67, a devout Catholic since his boyhood in Syracuse, New York.

His faith prohibited him from violence, so he volunteered to work as a medic.

He spent seven months in the jungle alongside Marines, all of whom were younger than 21-year-old Matthews, as they tried to cut supply lines to North Vietnamese forces.

The last six months of his tour were spent in an environment much more in line with his faith.

He worked as a scrub nurse in a hospital “like a MASH unit you’d see on TV,” he said. The hospital treated the wounded, regardless of whether they were “friend or foe.”

“Even if they were wounded prisoners, we took care of them. We didn’t ask ‘name, number, and insurance card, please,’” he said.

He and the other medical personnel came to refer to the unit as a “car wash.” Patients were stripped of their clothing, washed, covered in antibiotics, and readied for the operating room.

Working in the hospital wasn’t without its own risks. In one case, a Vietnamese farmer showed up with a small wound in his chest and the medics cleaned him up for surgery.

“We were just getting ready to cut him to fix the wound in his chest when the X-rays came in. There was a 40-millimeter unexploded mortar round in his chest,” he said.

He helped the doctor carefully remove the mortar with obstetrical forceps covered with rubber tubing. Always one for humor, Matthews joked that he needed a clean pair of underwear after the bomb disposal unit carried away the mortar round.

His aversion to carrying a gun incited some “snide remarks” at the gun range one day. Unbeknownst to his fellow soldiers, Matthews had earned an expert badge with the M-16 rifle. He accepted a $110 bet that he couldn’t hit the target once. He hit it five times.

“I knocked the head off the target, dropped the clip, gave the gun, gave the clip, said ‘thank you,’ and walked away $110 richer,” he said with a laugh.

He left active duty shortly after he returned from Vietnam but served as a scrub nurse in the New York Army National Guard and then the Army Reserve.

In 1990, he served in the Persian Gulf War at a 1,000-bed hospital in Oman designed to treat victims of biological or chemical weapons. The hospital remained empty throughout the war, making his time there rather uneventful.

“All I did was work on my volleyball serve and eat peanut butter and jelly sandwiches,” he said.

He moved to Florida after the war ended and worked as a scrub nurse at a Veterans Affairs hospital.

“I got good at my job and I actually liked going to work,” he said. “The pay wasn’t the best, but I thought I was doing some good.”

“Somebody would come in with a break or a problem and I was part of the solution to fix it and they went out the door cured or fixed or whole. That made me feel good,” he said.

He retired as a scrub nurse in 2008 and moved to Marana.

For the past six years, he has volunteered at the VA hospital in Tucson as a concierge, helping veterans make their way around the hospital. He also is a Eucharistic minister at Our Lady of the Desert Church.

More than four decades have passed since Tom Parker served in Vietnam, but he still feels the impact of his wartime experience.

The Air Force Buck Sergeant was sent to Vietnam in 1970, shortly after enlisting as a way to avoid the Army draft and, ironically enough, combat.

Serving in an intelligence role, Parker worked in forward air control, marking targets for fighters with smoke in the air, telling them where to drop bombs. On occasion, he went up in planes as an observer.

He also briefed pilots on what was happening in the area, advising them of where the enemy was and where they could safely land if needed.

“It was a rather pretty place and I always thought if it weren’t for the war it would be an interesting place to go as a tourist,” Parker, now 66, said of Vietnam.

But there was a war and with that came gruesome scenes that did a number on Parker, who to this day suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

“When I would go up in the planes, you see dead bodies and things like that, some of the destruction,” Parker recalled. “And because of my job I knew the impact we had — particularly the collateral damage.”

|

It took Parker 35 years to seek treatment for his symptoms, which included disturbing dreams, anger, anxiety and suicidal thoughts. He felt fortunate to have been pulled aside by two pilots in Vietnam who connected him with a Christian group called the Navigators.

“That’s what kept me out of a lot of the stuff that would have otherwise run my life into the ground,” he said.

Today, thanks to his faith and help from Veterans Affairs, Parker says his PTSD is manageable and he believes the events that occurred happened so he could serve others.

As part of the organization Operation Eternal Freedom, Parker works with current and former service members as well as civilians who suffer from PTSD, sharing coping mechanisms, resources and encouragement through the faith-based program.

“The thing I found is, this whole PTSD thing is more than mental, it wounds the soul. It cuts against the very core of who we are,” Parker said. “To me, we need to go to the one that made us in order to have that heal, and that’s Jesus Christ.”

The challenge, Parker says, is getting those affected to recognize it and seek help. But when they do, Parker is there.

“These guys fought to keep us safe and we need to fight to keep them alive with what they’ve done for us and the price they’ve paid both physically and mentally,” Parker said.

Parker still encourages others to serve their country.

“It gave me a chance to grow up,” he said. “If you don’t know what you want to do, it’s a viable option. It’s a secure environment, you’re fed, you’re clothed, you’re paid, you learn discipline, good work ethic,” he said, “which is something a lot of younger folks may be lacking, and they can learn a skill, too.”

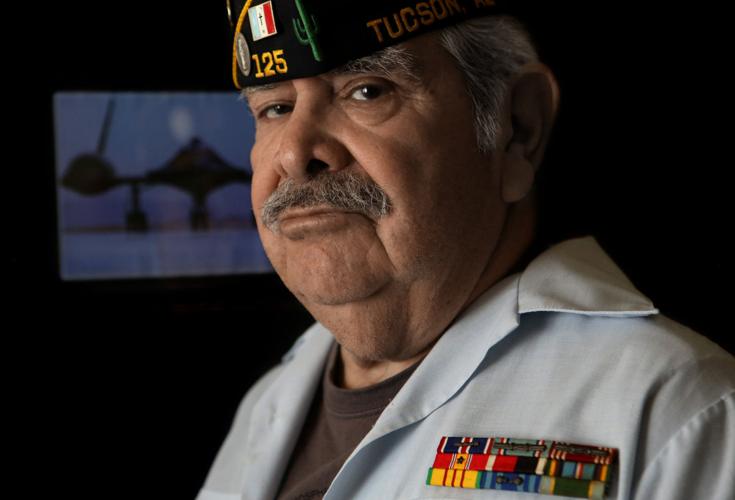

Benjamin Arellano learned the importance of patience and precision in the Air Force as a parachute rigger.

The Tucson High School student left the Old Pascua Yaqui Village at age 17 and joined the Air Force in 1955, and at a young age became responsible for the lives of others piloting and jumping from aircraft.

|

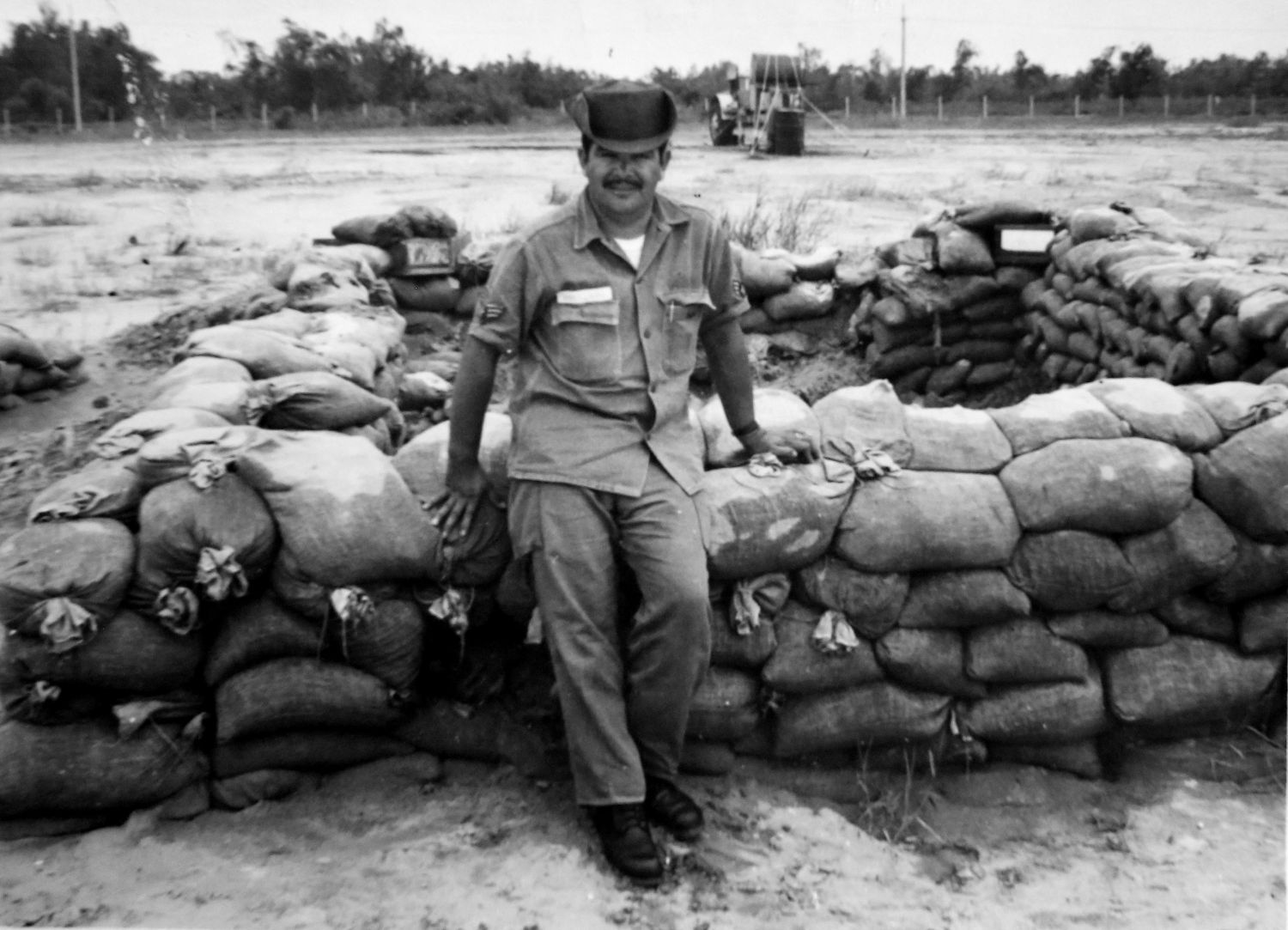

It was his job to make sure the pilots’ parachutes were folded and packed correctly while flying their training missions from bases in the United States, and then taking care of his comrades abroad, including in the Vietnam War, and then later as a ground crew member of the SR-71 Blackbird spy plane.

In addition to pilots, Arellano’s hands also touched the lives of paratroopers.

While his family remained in the Phillipines, Arellano left Clark Air Base with the 450th Fighter Day Wing to join service men in Vietnam. He served at the Da Nang Air Base 90 days at a time in 1963 and 1964.

“I packed chutes for different outfits in battle,” recalled Arellano, 78, from the living room of his home in the New Pascua Yaqui Reservation, southwest of Tucson. His son, Benjamin Arellano Jr., and his son’s wife, Dolores, proudly sat nearby listening to Arellano share his stories.

|

“The chutes were for different outfits in battle. There were Army paratroopers and special forces. I packed chutes for up to 60 soldiers. They flew in C-119s — the Flying Boxcar,” said Arellano, recalling the military transport plane.

As a parachute rigger, Arellano learned his training and skill at several bases including Chanute in Rantoul, Illinois; Foster near Victoria, Texas; and Luke in Glendale, Arizona, where he was with the 4510th Combat Crew Training Wing.

In 1966, Arellano and his wife, Juanita, and his two sons left Clark Air Base and returned to the states. Arellano was stationed in Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas. Two years later, Arellano described his assignment to the ground crew for the SR-71 Blackbird as his “pride and joy.” He was sent to Beale Air Force Base near Marysville, California.

|

For the last 10 years of his military career, Arellano, who retired as a staff sergeant in 1975, packed chutes for the crew and the SR-71 Blackbird, a long-range Mach 3 plus supersonic speed reconnaissance aircraft. He was assigned to the 9th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing.

“I packed three chutes. One was a drag chute, the other was for the pilot’s seat and the navigator’s seat. The pilot’s chute alone took six hours to pack,” recalled Arellano, who received numerous honors for his service, including three Outstanding Unit Citations, Good Conduct medal, two Vietnam Service medals and a National Defense Service with a Bronze Star ribbon.

After his retirement in 1975, Arellano went to work for the Tucson Airport Authority and later for the Pascua Yaqui tribe at the casino.

Charles Wohlleb woke up one morning in December 1944, and for some reason, he felt like he should put his life jacket on.

He was working in the engine room on the USS Spence, a Fletcher class destroyer, near the Philippines, which was occupied by the Japanese at the time. He was not on duty, and the seamen were not required to keep their life jackets on.

“Something told me to put it on,” he said.

And then the typhoon came.

|

Wohlleb, now 91 years old and living on Tucson’s west side, is one of only 24 survivors from the ship, which capsized and sank; 315 others aboard died.

Typhoon Cobra, which he later found out was responsible for capsizing the Spence, sank two other ships, the USS Monaghan and the USS Hull.

The Spence was desperately low on fuel at the time, he said. It tried three different times to fuel up from bigger ships, but failed because of the high winds and waves.

“The ship was rolling something terrible,” he said.

|

He and two other seamen went up to the deck as the storm was getting nastier. They were up there for about 15 minutes when they heard “Fire!” in the phones, which one of them remembered to bring. But the men didn’t know where the fire was.

“There’s a lot that I would like to know,” Wohlleb said.

Then the ship began tilting, he said. Stacks, which are chimneys on the ship, collapsed. And suddenly, he couldn’t see his friends anymore.

Wohlleb said he went about 20 feet underwater when he remembered he was wearing a life jacket.

“I squeezed it and went up like a rocket,” he said.

He saw the ship tilt until it turned upside down with everybody inside.

“That’s the part that gets me,” he said.

He spent the next four days in the ocean with other men who survived by clinging on to a net. He said when the ship first sank, there were about 35 men on the net.

By the time they were rescued by another ship, there were far fewer. The heavy storm and waves claimed the lives of those who couldn’t cling to the net any longer.

|

Wohlleb, being the only one with a life jacket, tried to help sailors who were slipping from the ropes of the net. He held one man, who seemed unconscious, against his chest to keep him warm.

But in the end, “I couldn’t help them,” he said.

When the surviving men saw an aircraft carrier passing by on the fourth day at sea, the sky was pitch black, he said.

“We yelled and we yelled and we screamed,” he said.

Many of them didn’t think they could be seen or heard, especially in the darkness, but someone in the back of the ship was alerted to their presence.

“The guy next to me started to cry,” he said.

Upon his return to the U.S., he was discharged and returned home to New Jersey. In 1948, he married May. He went on to open an automotive transmission shop before moving to Tucson in 2003.

|

Wohlleb said it took more than 20 years to come to terms with what happened when the ship capsized.

Family and having a business helped him get through it. He joked that his kids, when they were growing up, gave him enough trouble that he couldn’t worry about anything else.

“You never forget it, though,” he said. “It’s with you all your life. I think about it every day.”

After completing a 12-mile march on an injured ankle as his final task in Army Ranger school, Charles Deibel knew there was nothing he couldn’t accomplish in life.

And now, as a University of Arizona senior, he says getting through college has been a walk in the park. He is preparing to apply to law schools on the East Coast.

He enlisted in the Army in 2008 as a 19-year-old and served four tours of duty in his four-year stint, one in Iraq and three in Afghanistan, earning a Purple Heart along the way in a firefight he prefers not to talk about.

“I was going to join right after high school, but I needed to do a little growing up,” said Deibel, now 27.

By the end of 2007, he was in a rut. His father told him his options were military or school, so he decided to scratch the public service itch and join the Army.

|

He says he didn’t join to gain respect or do something heroic, but that he didn’t like seeing people he didn’t know fighting for him and his family.

Deibel started in the infantry, but wanted to go further.

“I went to them and asked them who’s the best,” he said. “I told them I wanted to do that.”

Ranger School consisted of nine weeks of training, but to join the 75th Ranger Regiment, he had to complete an additional three weeks of pre-Ranger training.

“Ranger training was a different kind of animal,” he said. “It taxes you mentally and physically to no other level.”

Deibel went through 12 weeks of physical training, tests, patrols, 22-hour days and peer evaluations. He was forced to repeat his third phase, which he said was a gut check to either quit or drive on.

The last activity in completing school was the march, but the day before, he’d fallen 45 feet during a rope training, severely injuring his ankle.

“The march was the turning point in my life as to how hard I was able to push myself,” he said. “The military never gets easier as you advance, but you earn more respect, and it just gets better.”

He left the Army in June 2012 and started school in the fall, knowing he needed a degree.

|

“I liked government, so I wanted to stay in that line of work,” he said. “It’s another type of public service.”

Deibel is majoring in political science with a minor in Arabic, and is preparing to take the LSAT exam for entrance into law school in December.

He’s undecided between pursuing constitutional, criminal or civil law at this point, but he’s interested in all three, and has time to decide.

Deibel won’t rule out returning to the Army, saying the JAG Corps is an excellent arena in which to practice law.

“The itch is always there, but it’s different now that we’re not in as deep of a war anymore,” he said. “I’d like to take my drive and focus elsewhere to help people in a different capacity.”

- By Patrick McNamara Arizona Daily Star

It only took about a month of college for John Lloyd Rhodes to learn academic life wasn’t for him.

“I went to UA because I wanted to play football,” Rhodes, 79, said. “I found out you had to read and study, so I joined the Marine Corps.”

That started a nearly 20-year journey for the native Tucsonan, who went on to serve in Japan, Okinawa and Vietnam, among many stateside assignments.

Rhodes initially trained as a ham-radio operator. That assignment took him to Georgia, San Diego and Washington, D.C.

Then war broke out, and Rhodes was off to Vietnam as part of a military police battalion in charge of security at the Da Nang Air Base.

Despite the war raging throughout much of the county, Rhodes said times in Da Nang were relatively quiet. After all, it was the place where many American troops took their rest-and-recreation breaks from the war.

But there were a few close calls.

Like the day when Rhodes was making a cassette recording for his wife Theresa back home and North Vietnamese fighters launched an attack on the base.

“I made the mistake of leaving the tape recorder on while we were under attack,” he said with a laugh.

What’s more, he sent it to his wife.

“I didn’t care for that,” Theresa said.

Things got more dangerous for Rhodes in the second half of his first deployment when he was reassigned to the Second Battalion, 26th Marines, or the “Nomads,” as he said they were known then.

There he participated in 13 major operations over six months all across the country.

“They say your first couple weeks and your last are the most dangerous,” he said, and that proved to be true in his case.

Of the 1,000 men in the battalion, 324 were wounded and 33 killed in action.

Rhodes was one of those injured when a mortar round exploded near him, sending shrapnel into his leg.

He downplays the injury, saying he got stitched up and sent on his way. The Department of Defense thought differently, however, awarding him the Purple Heart for his service.

Rhodes left Vietnam shortly after the incident for an assignment in San Francisco.

It was quite a time to be in the City by the Bay — 1967 and the height of the counterculture and antiwar movements.

Rhodes said his time in San Francisco left him discouraged, as the base where he worked became the frequent target of domestic assaults. So common were the incidents of people shooting or hurling projectiles at the base that officials had to install bulletproof glass on the guard gate.

“I felt safer in Vietnam,” Rhodes joked.

He returned to the war-torn country for a second tour. After a safe return stateside, he took a job with the U.S. Marines Inspector General’s Office.

That job took him to Marine facilities all over the world.

In a fortuitous twist, Rhodes’ final assignment before his retirement from the Marines was back home in Tucson.

“The last thing I did was inspect the reserve unit I started out in,” he said.

Rhodes left the Marines in 1974. He earned a degree in agriculture from the University of Arizona, and later worked as a real estate appraiser until he retired in 2007.

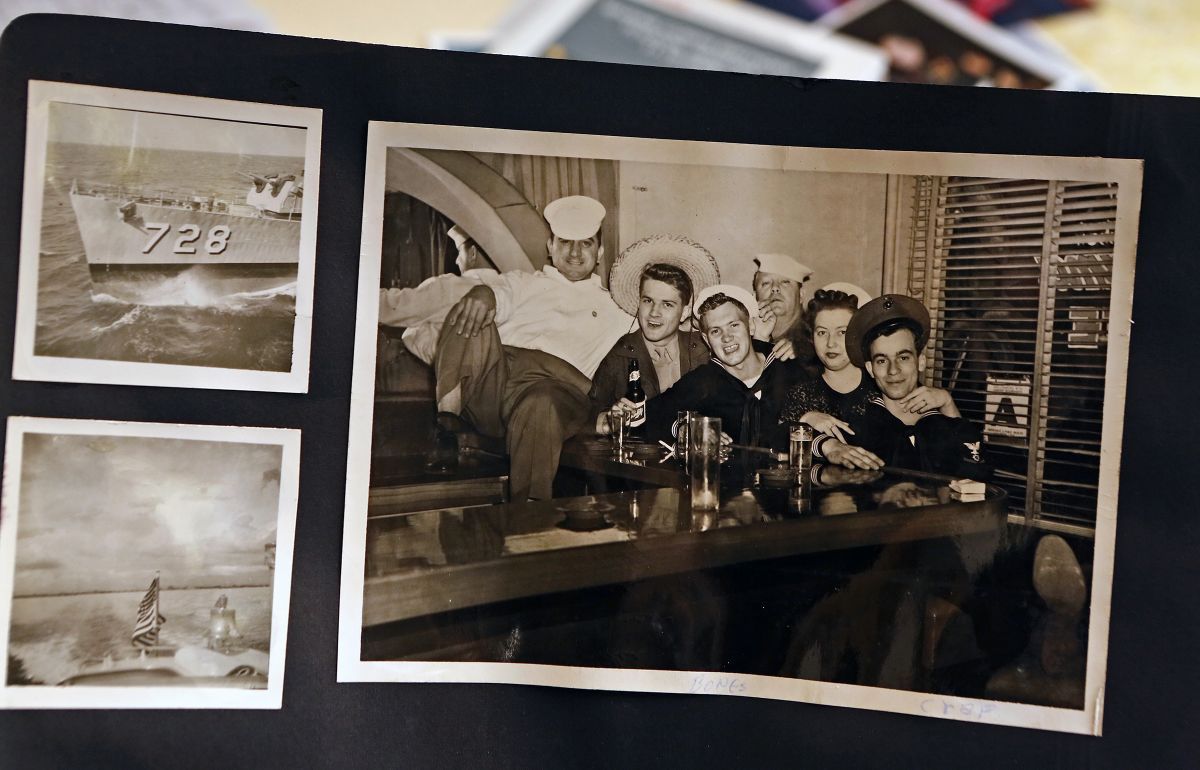

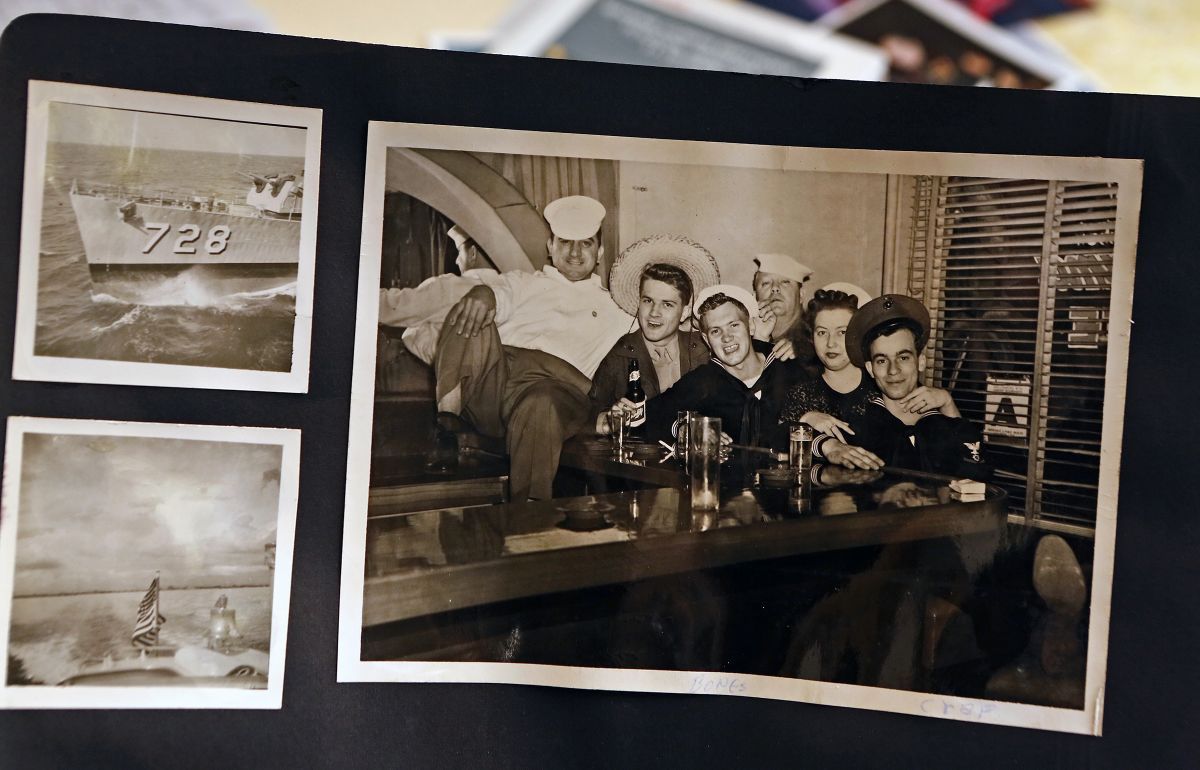

John and Leo Lochert fondly recall their two years in the Navy.

Their time in the Army? What comes to mind for John is “dirt and mud and cold and ugh.”

The 88-year-old twins, whose birthday is Dec. 7, served in World War II in the Navy and then in the Korean War in the Army.

|

In 2013 they took an Honor Flight trip to Washington, D.C., to visit the “impressive” war memorials and monuments. They reflected on their military experience in a recent interview.

In 1944 in Dickinson, North Dakota, the twins were 17 and subject to the draft. They didn’t want to be in the Army, so they volunteered for the Navy.

“I thought Navy would be a better duty,” Leo sad.

“It was!” John said.

So two days after high school graduation, before the ceremony and the prom, the twins started their military careers.

They went to boot camp and then a 6-month course at the University of Idaho to learn to be radio operators to send and receive encoded messages. It was a fun time with a lot of invitations to sorority dances because “they needed boys” with most of the local young men gone during wartime.

|

When they got their service assignments, they were shocked to learn they couldn’t stay together. They’d never been apart.

“It was terrible, really. It hurt,” John said.

Leo pleaded with his commanding officer to let the brothers stay together, but after the five Sullivan brothers were killed when the USS Juneau was sunk in the South Pacific in 1942, the Navy enforced its ban on siblings serving together. They were sent to their separate assignments in the South Pacific and served for two years in the Navy.

“Some old tin-can destroyer he got, and I got a carrier,” John said.

After the war, both ships were decommissioned and the twins went home. To help pay for college, they joined the Army National Guard as master sergeants to get financial help going to college. They were trained for a medical unit.

“This was when the Korean War was going on.

|

Our commanding officer said, ‘Don’t worry, folks, we’re not going to get called up,’” Leo said.

Two days later, they were.

“He got the .45; I got the M1 rifle,” Leo said.

John accepted a battlefield commission and was sent overseas, followed by Leo. But this time the brothers were allowed to serve together, and Leo sometimes wore John’s uniform to sneak into officers’ clubs with him.

They worked at forward first aid stations where the wounded were brought, sometimes without legs or arms, sometimes in body bags. “It was terrible,” Leo said. “The worst I’ve seen.”

They served together two years in the Army for two years. John served a third year, and they both finished college.

John had a career in accounting, and Leo had a career in baking and restaurant work.

Leo had four sons and four daughters with Dorothy Jean Cox, and they moved to Tucson. After they divorced, Leo married Buffy De Trouville. John joined Leo in Tucson.

These days, you can hear the twins singing in the church choir at St. Thomas the Apostle Church.

- By David J. Del Grande For the Arizona Daily Star

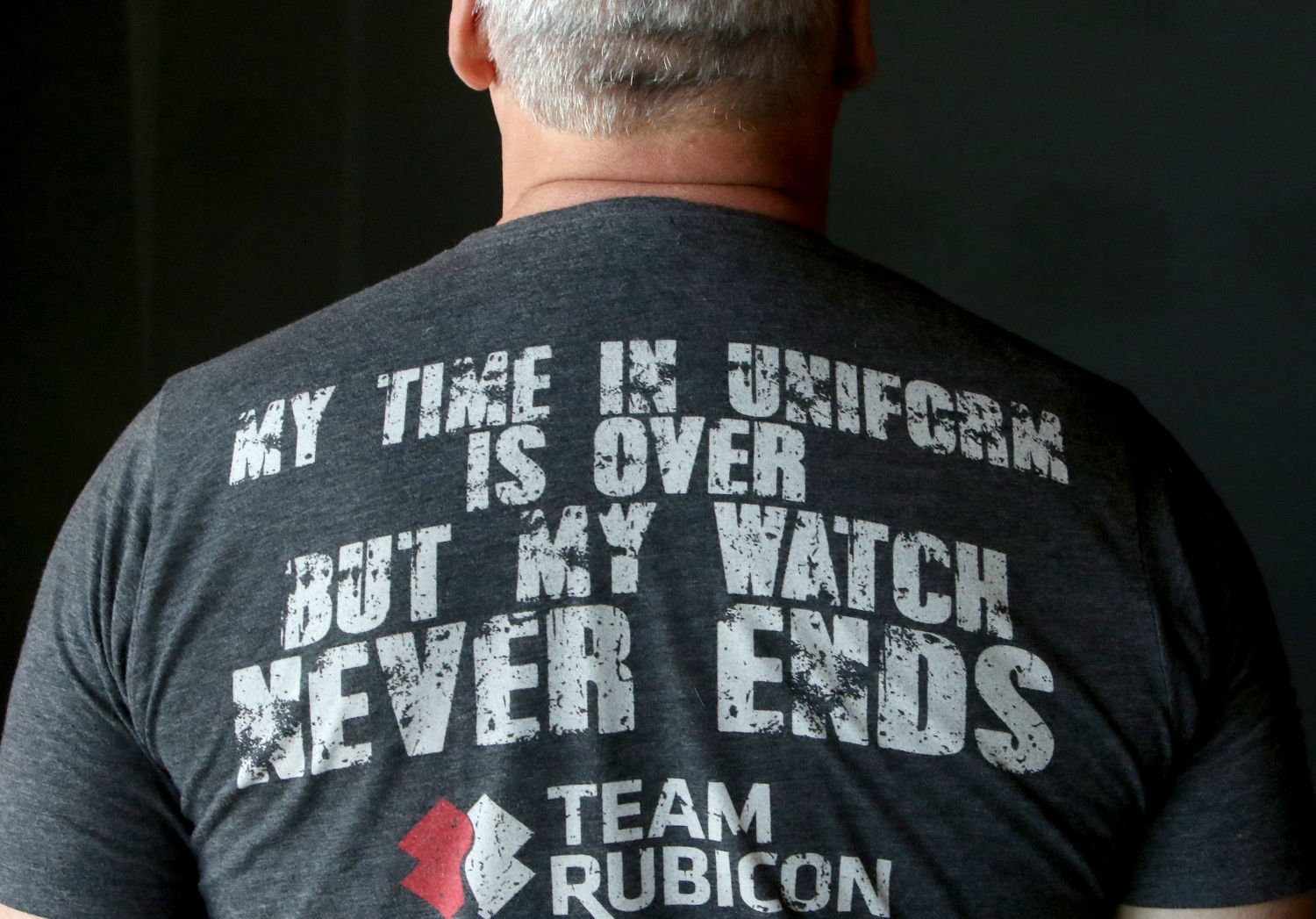

Some people may be skeptical about the morale and good work being done throughout the country, but retired Marine Sam Brokenshire isn’t one of them.

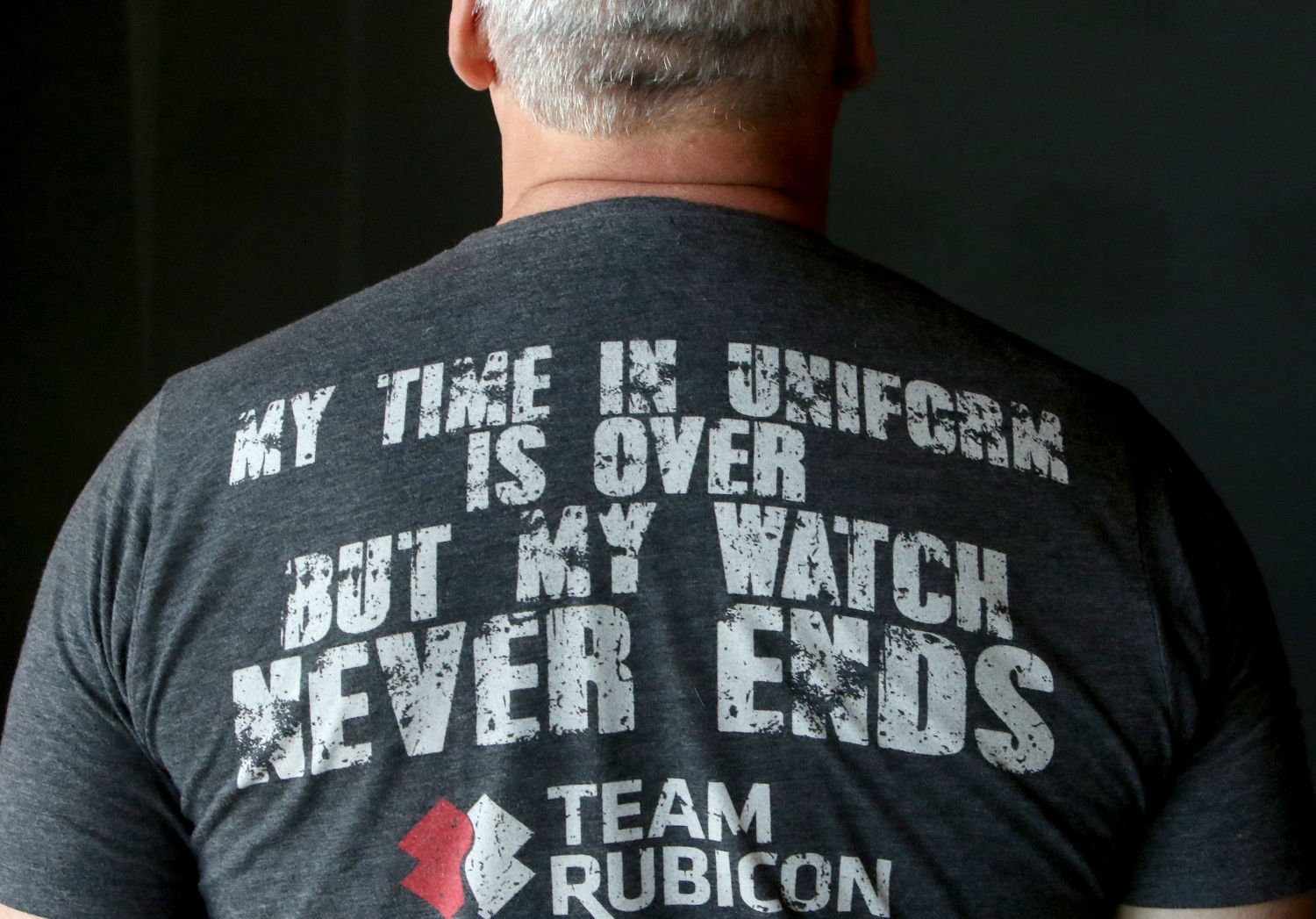

Brokenshire is one of the many retired service members who now works for Team Rubicon, a volunteer disaster relief organization for veterans.

“There’s a feeling in America right now that we’re on the decline, but being on these deployments and seeing all these young veterans coming back, I think we’re just at the beginning of our greatness again,” Brokenshire said.

|

He registered with the group one year before retiring as a corrections officer, and now holds Team Rubicon’s regional field operations manager position which oversees Arizona, California Nevada and Hawaii.

And Brokenshire’s warm, reserved smile grows when talking about the unofficial Rubicon slogan adorning his T-shirt which touts, “My time in uniform is over, but my watch never ends.”

Becoming involved with the organization is a way for returning soldiers to reintegrate, and have a mission just as important as active duty, Brokenshire said.

“I think that is what’s therapeutic about Team Rubicon,” he said, “you can reacquaint yourself with what was important to you at one time that was lost.”

Brokenshire just returned home from the relief effort in South Carolina. And, not only did the group’s mission help other veterans, but its message relays a positive narrative many people are unaware of, he said.

“There is good being done out there,” he added.

The stout, soft-spoken retiree from Scranton, Pennsylvania, failed his first attempt at the Marines, in officer candidate school.

He had already earned his bachelor’s degree from Pennsylvania State University, so Brokenshire began teaching at Wallenpaupack Area High School.

But, Brokenshire said he felt dissatisfied with the teaching position and after two years decided to enlist. “It was always eating at me, that I had not succeeded,” he said.

Brokenshire went through basic training in Parris Island, South Carolina, and became a military police officer in San Diego.

After two years of exemplary service, Brokenshire earned an embassy duty position. Between 1984 and 1986 he served in both Paris and Mogadishu, Somalia.

He was on active duty until 1991, and settled in Tucson after returning stateside.

One year before retiring from his corrections officer position, Brokenshire joined Team Rubicon and began his new full-time mission.

Katie Whichard, a Team Rubicon regional deputy communications manager, also found a second home at the organization after retiring from the Marines last October.

Whichard said team members like Brokenshire embody Team Rubicon’s mission.

“He’s one of those standout people who have put his heart and soul into this,” Whichard said. “He’s the go-to-guy, and he seems to have all the answers.”

Whichard further said Brokenshire’s graceful leadership skills are invaluable whether he’s working side-by-side with a team or directing an effort remotely.

Brokenshire comes from a place of genuine concern and humility, Whichard said.

“He not only helps out the victims of these disasters but he helps out the volunteers with their lives,” she said.

John Moore will forever remember Thanksgiving Day 1968. It has nothing to do with turkey and stuffing — but rather with a traumatic, life-threatening experience.

A Marine serving in Vietnam, Moore was on a patrol to knock out an enemy mortar position when he and his fellow soldiers came under a barrage of mortar fire. One of the mortars landed close — very close.

“The shrapnel hit me and threw me over on my side,” said Moore.

|

“All 10 of us (in the patrol) were hit. I had shrapnel in my elbow and leg. I was terrified.”

Moore, who is now 67, was alive, but he was bleeding and in great pain as he and others were loaded onto helicopters for evacuation.

“I never stopped bleeding until I hit the operating room,” he said.

Moore, who also suffered hearing loss, lost part of his elbow and has shrapnel in his body to this day.

After his condition was stabilized, Moore was flown to a naval hospital in Japan for further treatment and then to a hospital in the United States, where he remained for three more months of care.

Later, after recovering sufficiently to work in a non-combat capacity, he remained in the Marines until receiving an early honorable discharge as a corporal in March 1970.

Moore’s path to the Marines and Vietnam began after his youthful years in Milton, Indiana, and a brief stint in junior college.

Unsatisfied with the college experience and looking for something new, Moore joined the Marines, completed training and arrived in Vietnam in August 1968.

He soon found himself in combat, often lugging eight grenades and seven canteens of water in addition to ammunition and other supplies.

“I learned there are so many ways to get killed,” he said, reflecting on his own close brush with death.

|

Moore, who moved to Tucson in 1970, worked on ranches and in other jobs before starting work with Pima Animal Control in 1983.

He worked there for 27 years before retiring in 2010.

Moore and his wife, Susan, have two grown daughters. One of them, Katee Moore, calls her father the “most compassionate, smartest, hardworking individual I have ever had the pleasure of knowing.”

In nominating him for recognition in the Star’s series of stories about veterans, she said “I truly believe that a veteran, a man, a father as wonderful and strong as John Moore should be recognized for the sacrifices he made for his country and the impact he has made on all the lives he has touched.

“There is an old quote associated with the military that goes ‘All gave some, some gave all.’ My father gave some of his body and all of his heart. He served with honor.”

When Harper Coleman jumped into the water at Utah Beach, he faced a sight nearly as daunting as the German guns trained on him: Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. waving his cane at the troops and yelling: “Go, go, go!”

“He was a rough talker,” Coleman, 93, said with a chuckle. “He wasn’t using any Sunday school language.”

Coleman, then 22, was among the first waves of troops to land at Normandy on June 6, 1944, also known as D-Day. More than seven decades later, a painting of the Normandy landing hangs on the wall of the Arizona room in his east-side home.

He stayed on the front lines as a private with the Army’s Fourth Infantry Division for the next seven months, fighting for the port city of Cherbourg, liberating Paris, and holding off the German offensive that came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

|

The Allied forces turned the tide of World War II in late 1944, but the momentous nature of the effort wasn’t at the forefront of Coleman’s mind.

“I was a kid. I didn’t think much about it,” he said.

Coleman had more immediate concerns, such as fighting his way through the hedgerows of France, which meant dealing with German defenses set up near the ancient rows of dirt, brush, and trees that separated farms.

“It was hop and jump the whole way from the beach to Cherbourg,” he said.

Eventually the Fourth Division made it to Paris, four years after German troops first occupied the city. “It was a big party. It was wild,” he said.

Several months later, the euphoria had dimmed and Coleman found himself fighting in “terrible” conditions against the last major push by the German military into northern France.

“There was snow up to your waist and mud you just couldn’t believe and somebody shooting at you,” he said.

Near the end of the Battle of the Bulge, Coleman and about 700 other soldiers in his division were sent to hospitals in England. Days of wearing wet socks and shoes had taken their toll and the soldiers suffered from trench foot. “Your feet just froze,” he said.

|

While in France, Coleman wrote letters back home to Kathryn McCleary in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. The two were married not long after Coleman returned to the United States and have been together ever since. Two of their children served in the Air Force and another served in the Army.

Although he had every intention of staying away from the Army after he returned to Pennsylvania, jobs were scarce and Coleman started working at a nearby armory depot. He continued working for the Department of Defense and in 1967 he took an electronic supply job at Fort Huachuca, where he retired in 1977.

Coleman’s efforts on D-Day brought renewed recognition two years ago when the French Consulate in Phoenix awarded him the French Legion of Honor.

“It may not mean much here, but if you’re in France, I’m a ‘sir,’ ” he said with a grin.

For as long as she can remember, Lupecelia Leon has sought out adventure.

When she declared she wanted to learn how to fly at the age of 16, her parents thought she was crazy.

Using the money she earned at her after school job at Burger King, Leon began taking flying lessons at Ryan Airfield.

Today, as a member of the Arizona National Guard, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Leon flies Black Hawk helicopters.

Having been deployed overseas three times and preparing for a fourth in the coming weeks, the medevac pilot has been in enough combat situations that she is no longer chasing thrills. Instead, she treasures time with her family.

It’s likely her adventures and thrills will continue.

The 33-year-old serves not only the country in her military career, but Pima County as a sheriff’s deputy and member of the search and rescue team since 2013.

No longer bewildered by their youngest daughter’s choices, Leon’s parents are proud of the path she has taken — something Leon has asked them not to draw attention to.

|

“To me, it’s nothing more than a job,” she said.

Her father, Pete, disagrees.

“Medevac pilots and their crew are unsung heroes who saved countless lives under enemy fire and extreme weather conditions,” he said.

Leon made the decision to enter into a life of service as a student at Sunnyside High School. She entered basic training for the Army in September 2000 — just four months after graduation.

She would remain in the Army through January 2005, when she enlisted in the Arizona National Guard.

Basic training was the first time Leon had been away from her family, and she admits she was nervous. But it was there where Leon says she learned the importance of teamwork. It’s a lesson that served her well during her last deployment to Afghanistan in 2011, where she flew her crew in to retrieve injured Marines and prisoners of war.

Knowing that her crew was capable of caring for the severely wounded on board, Leon was able to focus on her responsibilities — getting out of danger and delivering those in need to medical services.

Over the course of a year, Leon flew more than 100 missions, including eight within a 24-hour period.

Even though she had previously been deployed to Qatar and Afghanistan, serving in administrative roles, this was the first time she had been exposed on a daily basis to the cost of combat — picking up Marines who had lost legs, or arms, or both.

Leon and her crew were also tasked with transporting injured civilians, which came with a different type of risk.

“We received intel that the main goal was to get a helicopter with the red crosses, so they would do things to get us to go out so they could study us,” Leon said.

“There were different occasions where they would hurt their children. One time, a little girl, I think she was 9, she got shot in the stomach by her dad because they wanted to time us — the man always had to get in the helicopter with their child, but we knew right away because we would see the way they would look at their watches.”

The overall experience was challenging for Leon, not because of the gruesome scenes but because of the self-imposed pressure to save everyone.

“The reality is you can’t save everyone and you want to,” she said.

When the bells rang, Airman 2nd Class Daisy Gates knew encrypted messages had arrived. The messages quickly needed to be sent to locations such as Washington, D.C., or overseas.

It was during the Korean War and she was a teletype operator in the 1063rd Communications Squadron at a relay center at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama.

The young woman, who in 1951 enlisted in the Women’s Air Force after graduation from Tucson High School, recalled her work at the center where she and the others received top secret clearance.

|

“We sent messages all over — from Washington, D.C., to locations abroad,” recalled Gates, 82, from her kitchen table at her east-side assisted living complex.

What the messages said were unknown to Gates. The sender and the recipient were the only ones who knew.

But the operators knew war was underway. It was during that time that Gates became tight with the other women in her squadron.

“I believe some messages could have saved lives. Some could have dealt with the movement of troops and bombing locations,” said Gates, who received recognition honors and awards, including the Good Conduct Medal.

There were days when the bells would constantly ring in the large room, which was lined with teletype machines set in rows. The building they were in was cement block — not constructed out of lumber — like the others. It was under guard at all times.

“We could read the tape by touching the punch holes, and all we could read is where the messages were going. We would punch in the locations and make sure each one went to the right teletype center,” explained Gates.

The operators worked shifts around the clock, and the shifts would change weekly. “That was hard. It was difficult for our bodies to adjust,” she said.

|

Her work at the teletype center was cut short in 1952 after Gates, who then was Daisy Steele, married her fiancé, Alden Gates. He, too, was in the Air Force.

She then applied for a compassionate transfer and was sent to March Air Force Base in Riverside, California, where Alden was stationed. She worked in the communications office at the base.

When Gates became pregnant, she was discharged. “That’s what they did back then,” she said of the military. Gates returned to Tucson and her daughter was born at St. Mary’s Hospital. Her husband was eventually stationed at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

Family photographs are displayed in Gates’ living room, including a black-and-white picture of her and her husband in uniform. Alden Gates served two tours in Germany and retired from the Air Force after 22 years. He then went to work for the postal service for 20 years. Alden, who suffered from Alzheimer’s, died in 2014.

The couple raised three children. Gates proudly points to photos displayed in her living room and mentions that she has 11 grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren. It makes her happy, she said, to share stories with them about her military service.

To this day, Thomas Rankin, 90, remembers his ninth bombing mission of World War II.

He was 19 years old and on a B-24 aircraft, a bomber, which flew missions over Europe out of England. He worked as a radio operator and a top turret gunner when the aircraft was struck by fire at over 20,000 feet.

“We thought we were going to go down,” he said.

Two crew members were seriously injured, he said. The pilot suggested the crew bail out from the airplane, but Rankin knew that would mean three of them would die, including himself, whose parachute was damaged.

Pieces of the aircraft were falling from the sky, he said.

The B-24 managed to land at an emergency airport in England, he said. Everyone survived.

|

“The ninth mission stayed with me,” Rankin said. “I remember every second of it.”

Rankin also remembered when, as a young man before the war, he was driving down a highway in San Francisco near the airport and saw a Lockheed P-38 Lightning aircraft take off.

“It pulled up and disappeared,” he said. “And I thought, ‘Wow. That’s what I want to do.’”

He said he had originally intended to join the Navy. His father was an officer in the Navy and a teacher at the Naval Academy.

He ended up being drafted to the U.S. Army Air Corps instead.

After World War II, Rankin paused his military service to attend college, where he studied mechanical engineering and math. He returned to the military two years later.

During the Vietnam War, he said he was on a 21-day rotation of 12 hours on and 14 hours off, flying missions into Vietnam, hauling cargo.

One of the more memorable cargo he hauled during that time was a control tower, he said. The plane often carried much more than it could stand. “It was hanging out of the back about 15 feet,” he said.

And on some days, he would be sent on “vegetable runs,” he said. He and others would be sent to a base where they could collect boxes of locally grown vegetables and distribute them to the troops. He got to taste the “real good stuff,” he said.

|

Rankin retired from the Air Force as a lieutenant colonel in 1969. He went on to receive a master’s degree in education and taught at Pueblo High School for 10 years. He held another job in the district working with computer programs for six years.

Last spring, Rankin was chosen to be one of 72 Arizona veterans to be on an honor flight to Washington, D.C., where the veterans visited war memorials.

He also spent 32 years as a volunteer at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, helping people prepare for their tax returns.

Looking back on his military experience, Rankin said he was lucky to have survived.

“I just did what was needed to be done in those times,” he said, “Sometimes it was dangerous. Sometimes it wasn’t.”

There’s no denying that Luke Burgan was born with military blood running through his veins.

By the time he came of age to enlist in 2010, the then 19-year-old Burgan was following in the footsteps of his grandfather, father and older brother.

“I knew my whole life I’d probably be in the Army,” he said.

|

He knew before he signed up that he’d be in the infantry with boots on the ground like his father, Clarence “Sonny” Burgan, who served three tours in the infantry during the Vietnam War. Burgan, now 25, joined the Army in January 2010, less than a year after he graduated from high school. He took some time for himself in between, knowing what was ahead.

“I knew that there were two wars going on at the time, and I knew I’d be going to one or both of them,” he said.

He shipped out to Afghanistan in December 2011, serving in the 4th Airborne Combat Brigade, 25th Infantry Division.

When asked what the war was like, Burgan takes a long pause before answering.

“Exactly what I expected,” he said. “But I went in with the right mentality. I think I was bred for that, almost.”

He suffered four concussions during his service, three during combat operations, of which he participated in almost 250 during his 11 months in the war.

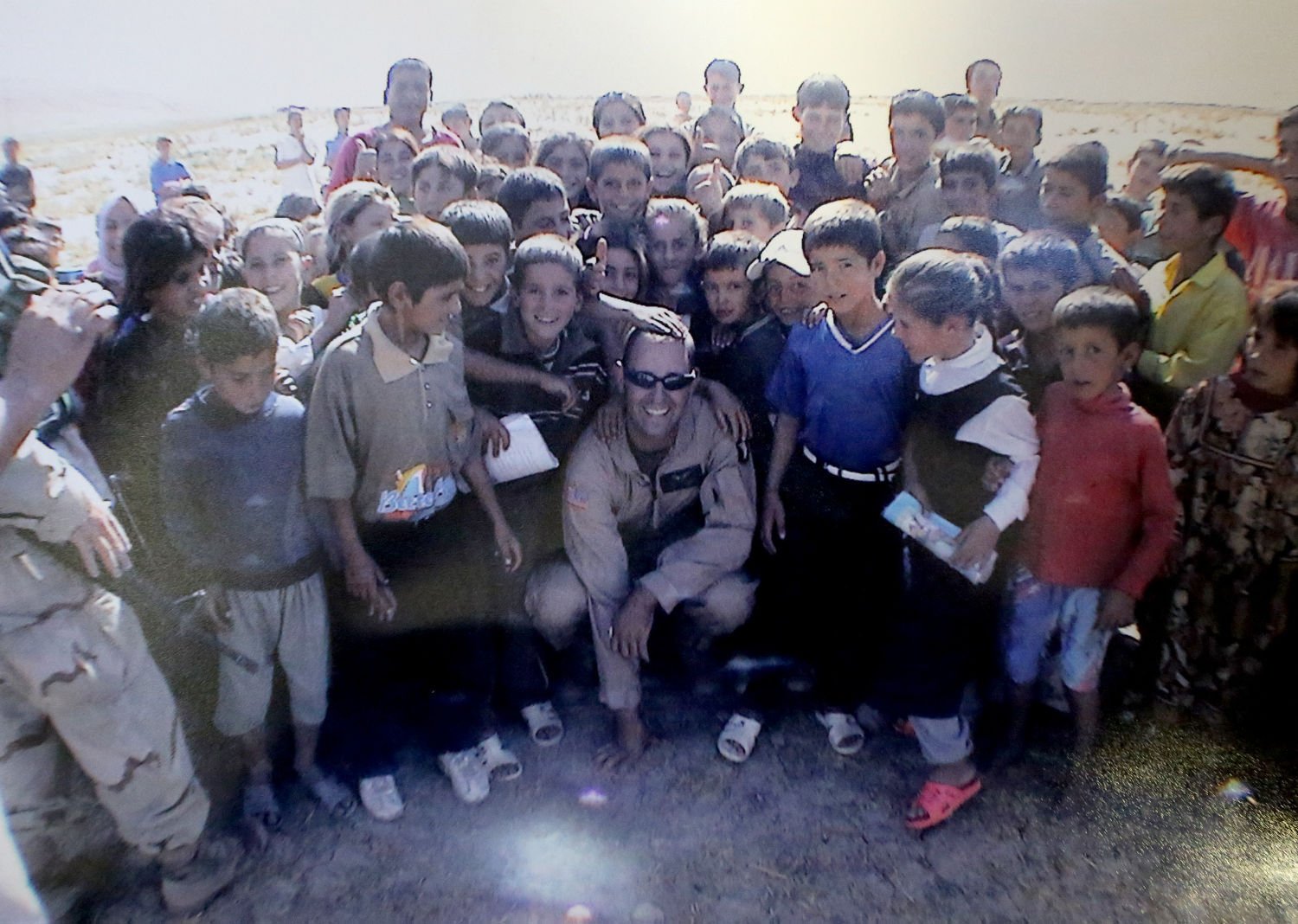

“I don’t care too much to mention the other stuff, but I want people to know that our soldiers do a lot of good work over there,” he said.

|

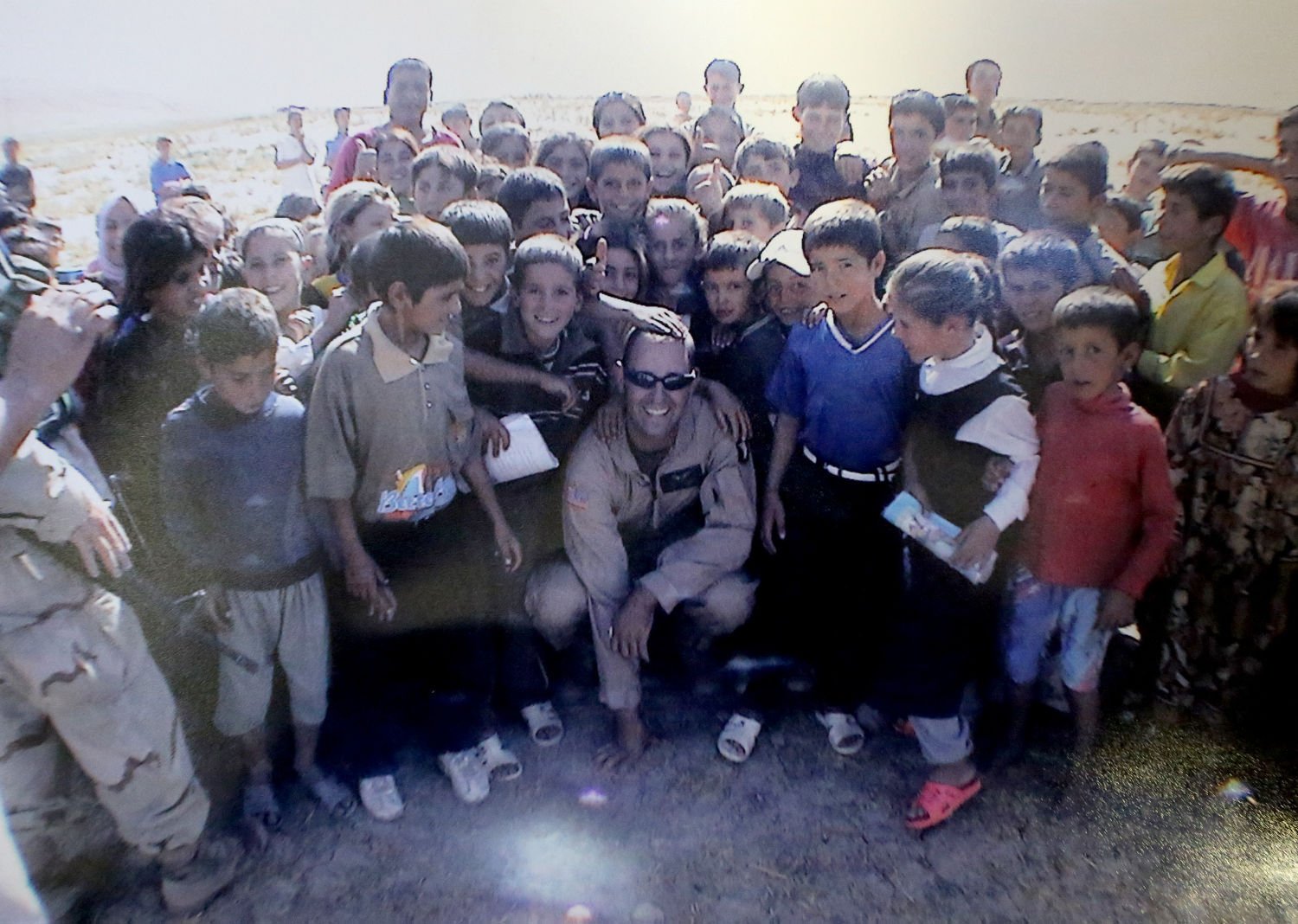

He speaks proudly of his experience in the Paktia Province of Afghanistan, where Burgan’s unit provided humanitarian aid and helped to increase stability in the area, even helping the community to reopen a local school.

“We didn’t have control of why we were over there, but the things we could control, we made a difference,” he said.

Burgan returned stateside in October 2012 and worked on a base in Alaska for the remaining year and half of his service.

“My original motivation to get out was to be with my dad and we were planning on moving him up to Montana,” he said of his father, who was ill. “It was the same day that I was signing out of the Army that he died.”

Burgan returned to Tucson instead and joined the National Guard, with no break in his service.

“It was something I’m really familiar with and it helped to ease the transition back,” he said. “I had some difficulty when I was first separating and experienced some mild anxiety.”