Johnny Thompson considers himself lucky.

The 68-year-old suffers blackouts and his short-term memory is shot.

Double vision plagues him. Sometimes he struggles to speak. “I lose words real bad,” he says.

On a good day, he can walk with a slight limp. On a bad one, he can’t take a step without the safety and security of a walker.

He served three tours of duty in Vietnam and each earned him a Purple Heart. He still carries a steel bullet — an armor-piercing round — in a spot so precariously close to the left vertebral artery and his spine that a doctor warned him to never be more than 40 minutes from a hospital.

This guy? Lucky?

“I still feel like the most blessed person in the world,” says Thompson.

Because, of course, he came home.

The veteran counts, among his blessings, a strong faith in God, three children — who all live within 15 minutes of his Marana home — nine grandchildren and his wife of 47 years, Gay. He might pick up his cellphone and not remember whom he wanted to call, but he can describe the day he first laid eyes on her, wearing a polka-dot dress, at a Texas church gathering when they were teenagers.

|

You’d never know about Thompson’s problems just by looking at him. He’s friendly, gracious and has a mischievous sense of humor.

“He’s dedicated, he’s compassionate — he’s just a good man,” says Andrew Bowers, an Army veteran who met Thompson through their church. “His heart shines through. He’s got a smile on his face all the time. He’s positive, he’s optimistic. Those ailments don’t hold him back. He has his bad days guaranteed — he doesn’t let it stop him.”

He did. Once.

At the darkest time of his life, Thompson admits he was suicidal, so depressed he could only sit on the couch. His body was wracked with seizures, and his memory and speech kept failing him.

A mistaken Alzheimer’s diagnosis at age 41 had him living his life in one-to-two-year increments. Now doctors know traumatic brain injury, coupled with the side effects of medications, caused his problems.

Despite his injuries, Thompson spent nearly three decades in the Army, assigned to several different units including Special Forces, and rose to the rank of chief warrant officer 4. Even in retirement, he’s dedicated to the military — and more specifically, those who served in it.

People come to Thompson, asking him to find out about their dads or their uncles or their grandfathers who have died. They want him to fill in the blanks because veterans, back in the day, just didn’t talk about what happened during war.

That uncommunicativeness coupled with a 1973 fire at the U.S. National Personnel Records Center in a Missouri suburb that wiped out millions of official military personnel records, make it even harder for relatives to research backgrounds.

The Thompsons scour the Internet, uncovering what they can. When they discover a veteran earned a medal, Johnny will track down a replacement for the family. He types up histories while Gay has even re-created embroidered naval ship patches.

|

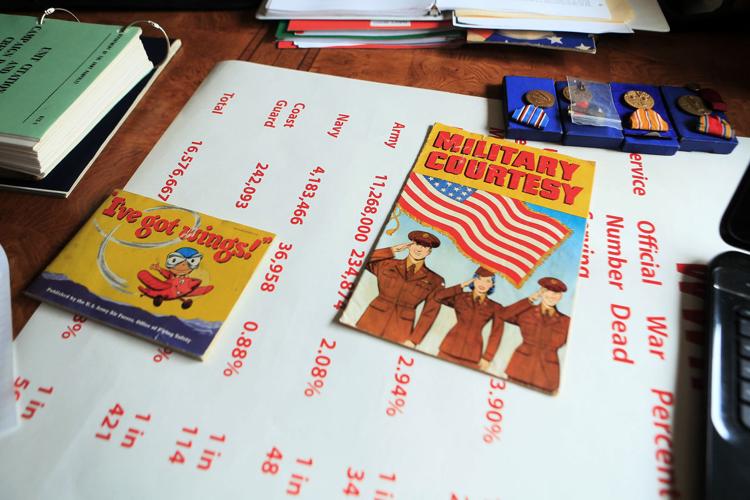

The two also curate traveling military history displays that have been displayed across the state at conventions and churches.

Some of Thompson’s Vietnam War mementos are on display now in Tempe (see box at upper right). Thompson got the idea when he took some keepsakes to the local veterans hospital about four years ago. He watched fellow patients’ eyes light up as he passed around a disarmed flechette warhead.

He’s managed to acquire so much stuff that three of the six bedrooms in Thompson’s house are devoted to military memorabilia. Even the one dedicated to the grandkids’ sleepovers is overrun with documents and uniforms.

Down the hall from the upstairs bedrooms, framed rubbings from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall decorate a sitting room.

Thompson chokes up when he points out the names belonging to two soldiers in his unit.

“The one thing you can’t stand about war is the people you can’t save,” he says, softly. “It’s the ones you lose — they’re the strongest memories you have.”

Thompson’s own medals and ribbons fill a shadow box hanging on the wall, but he won’t talk about those.

“A lot of people don’t get anything when they should have,” he says.

The son of an Army Air Corps experimental test pilot who helped design helicopters, Thompson was just 16 when he enlisted. A doctor realized he was underage and blew the whistle on him. Undaunted, Thompson enlisted again the next year.

After he graduated from flight school, and even though he had a wife and young kids, Thompson volunteered to go to Vietnam.

“I could rescue people,” he says. “I knew I could help people.”

The master helicopter pilot ended up serving three tours of duty in Vietnam and though the United States’ role was controversial, Thompson had and still has no qualms.

|

“Free the oppressed. I believe that with all my heart.”

His third and final tour in Vietnam was the worst.

“We went over with 83, 84 guys,” he says. “Only 22 returned home.”

Thompson himself barely made it.

He remembers the mission he flew on May 19, 1971, Ho Chi Minh’s birthday and two days after his own. It was one he’d flown solo many times before, but on this occasion, it was in a new Huey helicopter — and with a co-pilot. Having Capt. Bob Jorgensen along with him that day saved his life.

“I was down low, looking for footprints,” Thompson recalls. He was hanging out the door of the chopper, scouting for signs of the enemy when more than 150 bullets peppered the helicopter while mines exploded from below.

“I was just shooting blood out of my neck,” Thompson says. “When I got hit, I lost control of the Huey. It was straight up in the air.”

Two bullets sliced through Thompson’s throat, hitting vocal cords and his larynx and almost completely splitting a vertebrae. Discs in his back were crushed from the explosions beneath the chopper.

Thompson passed through six or seven hospitals as he made his way back home. “Everywhere I went, everyone said, ‘How are you still alive?’”

Thompson does what he can to make every minute count, which is why he spends so much time and effort on researching fellow veterans’ military histories.

Even with Gay’s help, it’s painstaking work. “It takes us a month what other people could do in two days.”

Thompson might spend four or five hours researching and writing what he learns. But the next day, that knowledge is lost. Completely wiped from his memory. He has to read over everything and reacquaint himself with the previous day’s work.

It’s frustrating, yes, Thompson admits. But it doesn’t deter him one bit.

“I’m going to keep going until I don’t know I’m doing it any more.”