About a year after the University of Arizona acquired a troubled for-profit school, its accreditor still has “strong concerns” about whether the new entity can properly serve its students. It’s sending a team of reviewers to find out.

An accreditation team plans to visit the UA Global Campus, a nonprofit online school formerly known as for-profit Ashford University, next month to see if the school continues to meet the standards of a degree-granting institution, which also allows it to keep collecting federal grants and loans.

That visit will come soon after Ashford and its former parent company, Zovio Inc. (formerly Bridgepoint Education Inc.) go to trial to face a consumer protection lawsuit in California. Opening arguments are scheduled to start Monday, Nov 8.

Meanwhile, the accreditor “has strong concerns that the targets set for academic improvement are seriously inadequate to reach levels of student outcomes that should be expected at an accredited institution,” Jamienne Studley, president of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Senior College and University Commission, wrote in a July 30 letter to UA Global Campus' top administrator.

The letter is a formal reminder that the new UA-branded entity and its earlier iteration, Ashford, have been operating under a “notice of concern” since mid-2019 — a detail the UA’s news release announcing the deal left out last December. The commission put the school on notice in 2019 due to “longstanding concerns regarding Ashford University’s student persistence and completion rates and performance on other student success metrics.”

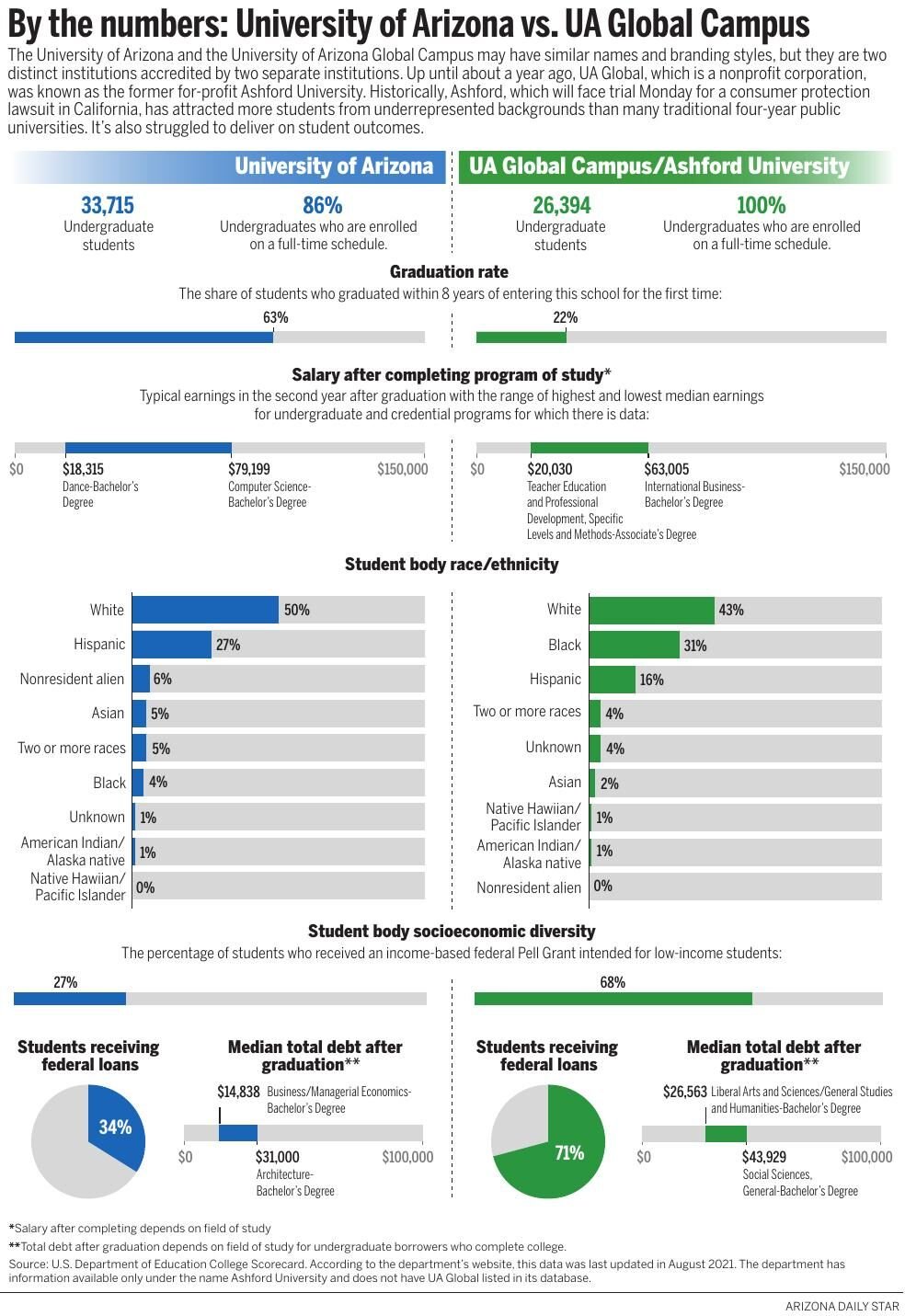

According to the most recent data available from the U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard, 22% of all Ashford students graduate in eight years, whereas 63% of UA students graduate in the same timeframe; 24% of first-time, full-time undergraduates returned to Ashford after their first year.

The commission also asked in 2019 for a response on issues of faculty workloads, resource allocation and financial governance, among others. The school responded to many of those concerns, which the commission reviewed and subsequently sent UA Global Campus the updated notice of concern this summer.

Out of the 212 total schools accredited by the commission, UA Global Campus is one of 11 schools with a notice of concern.

That status means a school meets accreditation standards now, but “is in danger of being found out of compliance with one or more standards if current trends continue.” Unless “significant improvements are made in the near future,” the commission wrote to Ashford in 2019, the online school “is in danger of being found out of compliance,” with standards for achieving educational objectives.

“If it wants to eliminate the concern about its performance,” Studley said in an interview with the Arizona Daily Star, UA Global Campus “needs to show it’s making improvements in student outcomes.”

UA brand on the line

Ashford, now UA Global Campus, has had more than two years to address the commission’s concerns. Whether the new UA-affiliated entity has improved to an acceptable level will be partly informed by the accreditor’s in-person visit in December to UA Global Campus’ headquarters in Chandler.

In February, the accreditor will consider the results of that visit when it decides what happens next for UA Global Campus. It could vote to remove the notice of concern, keep it in place — or take the more serious step of sanctioning the school.

A sanction would put UA Global Campus one step closer to losing its accreditation altogether, which would make the online school ineligible for the federal grants and loans that make up the majority of its tuition revenue.

Although this accreditation review process has been ongoing since 2019, a lot has changed since it started, chiefly the UA’s acquisition of and affiliation with the school. Now, no matter what the accreditor decides, the reputation of the UA — Arizona’s flagship university — will be tied to the outcome.

That’s one reason why the partnership has faced both external and internal criticism from faculty, student achievement advocates and two federal lawmakers.

“We believe UA’s embrace of Ashford through this transaction poses major risk for your current students and your institution’s reputation as one of the nation’s top public universities,” Democratic Sens. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Sherrod Brown of Ohio wrote last year in a letter urging UA President Robert Robbins to reject the deal.

In June 2020, faculty members from the UA’s Eller College of Management characterized the impending acquisition as a “catastrophic mistake” that would expose the UA to “litigation, impede our ability to compete in the high-quality online space, and harm relationships with current and prospective donors and faculty.”

A Faculty Senate survey in August of 2020 showed 80% of 1,074 faculty members who responded were against the deal and most “were extremely dissatisfied” with the UA’s handling of it.

At the time of the UA Global Campus deal, as the COVID-19 pandemic cast uncertainty on the UA’s budget and in-person learning offerings, the UA had about 7,000 students enrolled in its own in-house online branch, Arizona Online. But attracting more online students — students whose norm is attending classes remotely, pandemic or no pandemic — is a competitive venture in Arizona. The combined number of online students enrolled at Arizona State University, the University of Phoenix and Southern New Hampshire University topped 200,000 last year.

Enter Ashford. It had roughly 35,000 students enrolled in its online programs in 2020.

‘Much-needed’ revenue sought

Establishing UA Global Campus will not only provide “much-needed, short- and long-term revenue,” Robbins said in a news release in August 2020, but it will also help the UA “expand its reach and live up to its responsibility as a land-grant university to provide access to quality education, will enhance our Arizona Online platform, (and) will further diversify our educational enterprise.”

Though the two schools are separate entities accredited by different agencies, the UA has four representatives, including a member of Robbins’ presidential cabinet, on UA Global Campus' board of directors.

“We are in full support of the University of Arizona Global Campus’ aim to broaden educational opportunities to nontraditional students,” UA spokeswoman Pam Scott said in an email response to the Star’s questions about the accreditation status. “Education enriches lives and it is clear the UAGC leadership and board of directors are committed to providing students a high-quality online education.”

Ashford, like many for-profit colleges, has historically enrolled more marginalized students than many traditional public, four-year universities. According to the most recent available from the department of education (which only has data for Ashford, not UA Global Campus), 31% of Ashford’s student body identify as Black, 16% identify as Hispanic and 68% received a federal Pell Grant, which is intended for low-income students.

Robbins’ most recent employment contract, which the Arizona Board of Regents approved in September, gives him a $30,000 performance bonus if he works with UA Global Campus and its board to make “substantial progress toward improving the student experience and outcomes,” which includes increasing course completion rates.

Linda Robertson, spokeswoman for UA Global Campus, told the Star via email that “retention and graduation rates are our No. 1 priority — because our students deserve nothing less,” and that the school is “fully committed to working with (its accreditor) to remove the notice of concern.”

In response to the commission’s most recent concerns that “the targets set for academic improvement are seriously inadequate,” Robertson said UA Global Campus “intentionally reported conservative targets,” in March 2021, “as new leadership was cognizant of the road before us and did not want to overpromise and underdeliver,” but that it has since “increased its goals and responded to the accreditor concerns.”

Earnings plunge

The UA acquired Ashford’s assets for $1 last November from Ashford’s former parent firm Zovio Inc., a publicly traded company that recently reported a 38.6% drop in third-quarter revenue compared to the same time period last year.

Zovio had $101 million in earnings between July and September 2020. This year it had $62 million, according to an earnings report released late last month.

The company also told investors that enrollment at UA Global Campus remains “challenged,” despite Zovio spending a third of its revenue on marketing and communications last year.

Robertson confirmed to the Star that UA Global Campus’ enrollment dropped from 34,598 students at the time of the acquisition in December 2020 to 29,665 this September.

“The brand completely changed; therefore, the drop was not unexpected,” she said. UA Global Campus “also has changed its enrollment and orientation processes to ensure that students are ready and prepared, and this has resulted in some decreased enrollment.”

Ashford’s enrollment has been spiraling for years, though. In 2012, it had more than 80,000 students enrolled online.

Under the terms of the UA’s acquisition of Ashford’s assets, Zovio provides recruitment and other services on a contract basis for UA Global Campus and receives 19.5% annual tuition revenue for the first 15 years.

That payment, however, is conditional on UA Global Campus getting a “guaranteed” revenue stream of at least $225 million over the same time period, which included an upfront payment of $37.5 million.

Accreditors approved the change of control and legal status last November. But the commission has since asked UA Global Campus to provide updated information about its contractual relationship with Zovio, its current financial condition and its implementation of an independent monitoring and marketing audit plan.

The UA wasn’t the first public university to strike a deal with a for-profit college. Indiana’s Purdue University and for-profit Kaplan University struck a similar $1 deal in 2018 to create the nonprofit public Purdue University Global.

With students back at UA for the fall semester, here's a look at the Tucson campus over the years compared to now.

A year after its launch, enrollment was “slower than expected,” reported the Chronicle of Higher Education, and the latest data from the federal education department shows a 33% graduation rate. According to a Securities Exchange Commission report, as of June, Purdue Global owed Kaplan $87.8 million.

Ashford and Zovio on trial

Perhaps it is too soon to gauge the long term financial outlook for UA Global Campus, but the consumer protection suit Ashford and Zovio (formerly Bridgepoint) are facing is going to trial Monday and could further illuminate details of the history UA Global Campus has inherited.

Former California Attorney General Xavier Becerra filed the complaint in 2017. It alleges that Ashford and Bridgepoint maintained a “true boiler room atmosphere,” pressured recruiters to make false promises and used illegal collection tactics when students — some who had discovered “their degree would not advance their career dreams” — couldn’t pay up.

Ashford students have a median total debt between $26,563 and $43,929 and graduates can expect to make between roughly $20,000 and $63,00 two years after completing their program. In comparison, students at the UA proper have a median total debt between $14,838 and $31,000 and graduates can expect to make between about $18,000 and $79,000 after two years.

“We intend to vigorously defend this case,” Bridgepoint said in a 2017 statement responding to the suit. “We look forward to sharing the facts and success stories of our students and our school, because we’re proud of our work and confident that we’ll be vindicated.”

UA Global Campus’ accreditor is aware of the court case and imminent trial, which will likely conclude before the commission completes its review in February. If the trial “raised or determined new issues we should pay attention to, we certainly would,” Studley, the accrediting agency president, told the Star.

The California case against Ashford is no outlier.

Over the years, Ashford and its former parent companies have been the subject of multiple lawsuits and investigations. All of the cases centered on claims that Ashford misled students or misrepresented its finances

In 2016, for example, the federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau ordered Bridgepoint (now Zovio) — to refund and eliminate $24 million worth of private student loan debt. Investigators found that Bridgepoint deceived borrowers, telling them they could pay as little as $25 a month, when the actual payments were much higher.

‘Not quick-fix problems’

Chris Madaio is vice president of legal affairs for Veterans Education Success, a national advocacy group for student veterans. He said the organization has received more than 100 complaints from veterans about Ashford and warned against the UA Global Campus deal.

Students associated with the military — veterans often have access to federal GI Bill money, making them targets of for-profit schools — made up 25% of the UA Global Campus student body this time last year.

“Fed me all the stupid lies,” one anonymous complainant from Arizona told Veterans Education Success about their experience with Ashford several years ago. “Cost way too much of my GI Bill and lost more money after I left this school because they continued charging.” Another veteran simply said that an Ashford degree “seems to be worthless.”

Madaio said it’s “incredibly concerning” that the UA agreed to the partnership despite knowing about Ashford’s accreditation issues and the active litigation against the online school.

“Simply because it has the name of University of Arizona, doesn’t mean that it’s equivalent in quality, instruction or recruitment tactics to the University of Arizona.”

Gary Rhoades, a professor of education at the UA who’s been a vocal opponent of the deal, said faculty members remain concerned about the quality of education UA Global Campus students receive.

Rhoades, who co-chaired a UA committee that provided input to senior leadership before the UA Global Campus deal was finalized, said faculty members raised questions about the accreditor’s 2019 notice of concern against Ashford.

“The administrative response was to minimize its significance, to say the name change and not-for-profit status would change matters, and to say other changes to remedy the situation were already underway and/or taken care of,” Rhoades recalled to the Star.

Those explanations, in his view as a higher education expert, are unsatisfactory.

“These are not quick-fix problems. This is a university with a decade of poor student outcomes,” Rhoades said. “You don’t improve student outcomes by changing the name of the place. You improve student outcomes by investing in structures and people that will support the students. We didn’t see evidence of any of that happening.”