Developers of the multibillion-dollar Hermosa mining project in the Patagonia Mountains are touting the Trump administration’s latest mine-friendly move to expand the list of federally designated critical minerals.

The U.S. Geological Survey announced plans late last month to add copper and silver to the list of minerals considered essential for U.S. economic or national security but highly vulnerable to supply-chain disruptions.

That list already included Hermosa’s two main products, zinc and manganese.

Officials for Australia-based mining giant South32 said they also expect their new mine to produce silver as a secondary product, and there is an adjacent copper deposit they could tap by extending the underground tunnel network now under construction, about 75 miles southeast of Tucson.

“Hermosa is not just a two-critical-mineral project; it has the potential to be a dynamic critical minerals district that will produce at least four USGS-listed critical minerals,” said Pat Risner, president of South32 Hermosa, in a written statement. “We look forward to responsibly delivering a domestic supply of the building blocks for a 21st century economy.”

But one Tucson-based environmental policy expert said other recent actions by the administration could strip the new mine of some of its biggest potential customers in the U.S.

Justin Pidot is a University of Arizona law professor who served as general counsel for the White House Council on Environmental Quality during the Biden administration and as the Interior Department’s deputy solicitor for land resources during the Obama administration.

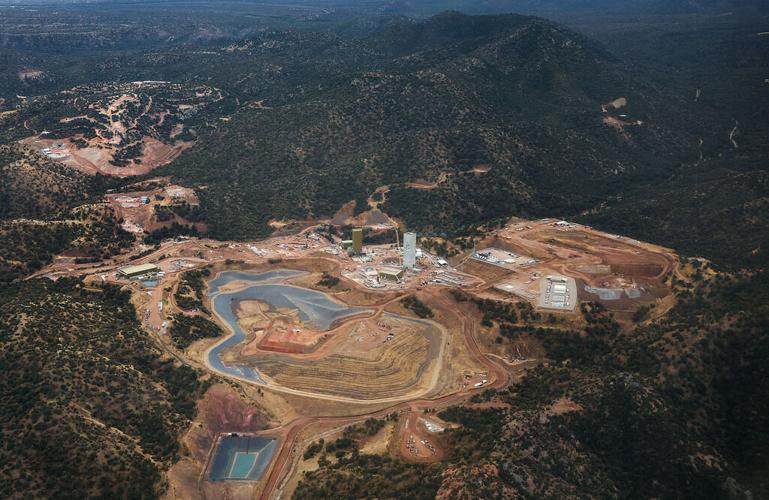

South32’s Hermosa mine site in the Patagonia Mountains, as seen from the air during an EcoFlight tour on Feb. 10, 2025.

He said South32 could end up exporting more of what it mines from the Patagonia Mountains as a result of President Donald Trump’s grudge against the green energy sector.

“One of the main domestic customers for a mine like this is the renewable energy industry, so as the administration does everything it can to squash that industry, it will, I think, have an effect on mining projects in terms of drying up some of their domestic customers,” said Pidot, now the Ashby Lohse Chair in Water and Natural Resources and co-director of the Environmental Law Program at the U of A’s James E. Rogers College of Law.

Ultimately, he said, the federal government’s hard pivot away from electric vehicles and renewable energy won’t make or break a project like the Hermosa mine, though there could be some additional costs associated with shipping material out of the country.

“The world has a pretty severe demand for copper and all of these various minerals, so I imagine they’ll be able to find customers and sell overseas,” Pidot said. “If you’re running a mine, your primary goal is to find customers, and you’re gonna find them wherever they are.”

Critical mass

In 2024, Hermosa received $20 million from the Department of Defense and up to $166 million from the Department of Energy under President Joe Biden to ramp up commercial-scale production of manganese for use in electric vehicle batteries.

Roughly 50 years have passed since manganese ore was last mined in the U.S. According to South32, more than 95% of the world’s supply of the battery-grade mineral now comes from China.

The multinational company plans to spend more than $2.5 billion to develop its underground mine on about 750 acres of private land in a historic mining district about 6 miles from the town of Patagonia and about 10 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border.

A newly released rendering shows Centro, the remote operations center that South32 is building in Nogales for its Hermosa underground mine the Patagonia Mountains.

South32 officials have called it the largest private investment in Southern Arizona history and by far the biggest financial boon ever seen in Santa Cruz County, where the project is eventually expected to inject as much as $1 billion into the economy annually and nearly double the overall property tax base.

The company is promising to create up to 900 good-paying jobs, including 200 full-time positions at Centro, the mine’s remote operations center planned for Nogales.

The mine is set to begin production in 2027 and could operate for 70 years or more, as the company excavates what it describes as one of the world’s largest untapped zinc deposits and potentially enough battery-grade manganese to meet most of U.S. demand for the mineral.

Meanwhile, conservation groups and local activists continue to fight the project in court — and in the court of public opinion — over concerns for its potential impact on neighboring communities and the environment.

As a result of one legal challenge from project opponents, the federal Environmental Protection Agency has ordered the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to revise portions of its air-quality permit for the mine.

The state agency is now accepting public input on those revisions, which have not limited construction activity at the site but will require some improved monitoring and reporting of air emissions than were spelled out in the original permit granted by ADEQ last year.

A South32 employee holds a core sample containing zinc ore during a 2024 media tour of the Hermosa mine site in the Patagonia Mountains.

The comment period ends on Sept. 25, the same day ADEQ will hold a public hearing on the permit revisions at 6 p.m. in the multipurpose room at Patagonia High School.

Historically, Pidot said, the critical minerals list hasn’t carried much legal weight. It’s mostly useful for identifying needs and prioritizing projects.

For that reason, the addition of copper seems counterintuitive to him, because virtually every mine produces some amount of the metal.

“I never thought it made sense to put copper on the critical minerals list, because as soon as you do, it means that every mine is a critical minerals mine,” Pidot said. “If everything’s critical, nothing’s critical. There’s no prioritization at all.”

Digging in

Copper industry leaders are cheering the move.

Adding Arizona’s official state metal to the list of critical minerals is “a national strategic imperative to counter rising imports and the concentration of production in China,” said Adam Estelle, president and CEO of the Copper Development Association.

“For decades, the flow of U.S. copper to market has been stymied by convoluted permitting, overreaching regulations, and a lack of strategic industrial policy to protect domestic producers from the trade-distorting practices of China and other non-market economies,” Estelle said in a written statement.

Though Trump has shown no love for certain types of major end-users in the critical mineral supply chain, Pidot said Hermosa and other Southern Arizona mines apparently can bank on the president’s support when it comes to mining in general and mineral development on public land specifically.

“If you’re a mining company or any other company, you play the hand you’re dealt. Whoever’s in power, you try to justify why your operation is going to be good for the priorities of that administration,” he said. “I think this administration is very focused on expanding mining, so in that way maybe you don’t need to do any more than say, ‘We’re a mine, we’re gonna mine some stuff, and that’s what you want.’”

Pidot said both the Obama and Biden administrations recognized the need to rebuild the domestic mineral supply, but in a sustainable, responsible way that was “sensitive to communities and the environment.”

“I think that the Trump administration is not really interested in that piece of the agenda,” he said. “They’re just interested in mining. They don’t really care about the environmental consequences of mining.”

In April, the Interior Department announced “emergency permitting procedures” to rush the development of coal, uranium and critical mineral mines, among other energy-related projects, by slashing reviews required by the National Environmental Policy Act. Environmental assessments that used to take up to a year were shortened to 14 days, while the typical, two-year process for environmental impact statements was reduced to 28 days.

Pidot called that an “unfathomably quick amount of time” that will allow for no real analysis or community input.

Gutting federal oversight seems like an obvious way to accelerate mineral production and reduce costs for mining companies, but it comes at a price, he said: human health will suffer, the environment will suffer and generations of taxpayers will be left to pay for the mess that’s left behind.

“If we really return to a world where we have no standards, and people are just mining in the cheapest, least sustainable fashion, we’ll have just a huge number of new sites that will continue to contaminate people and the environment for decades,” Pidot said.