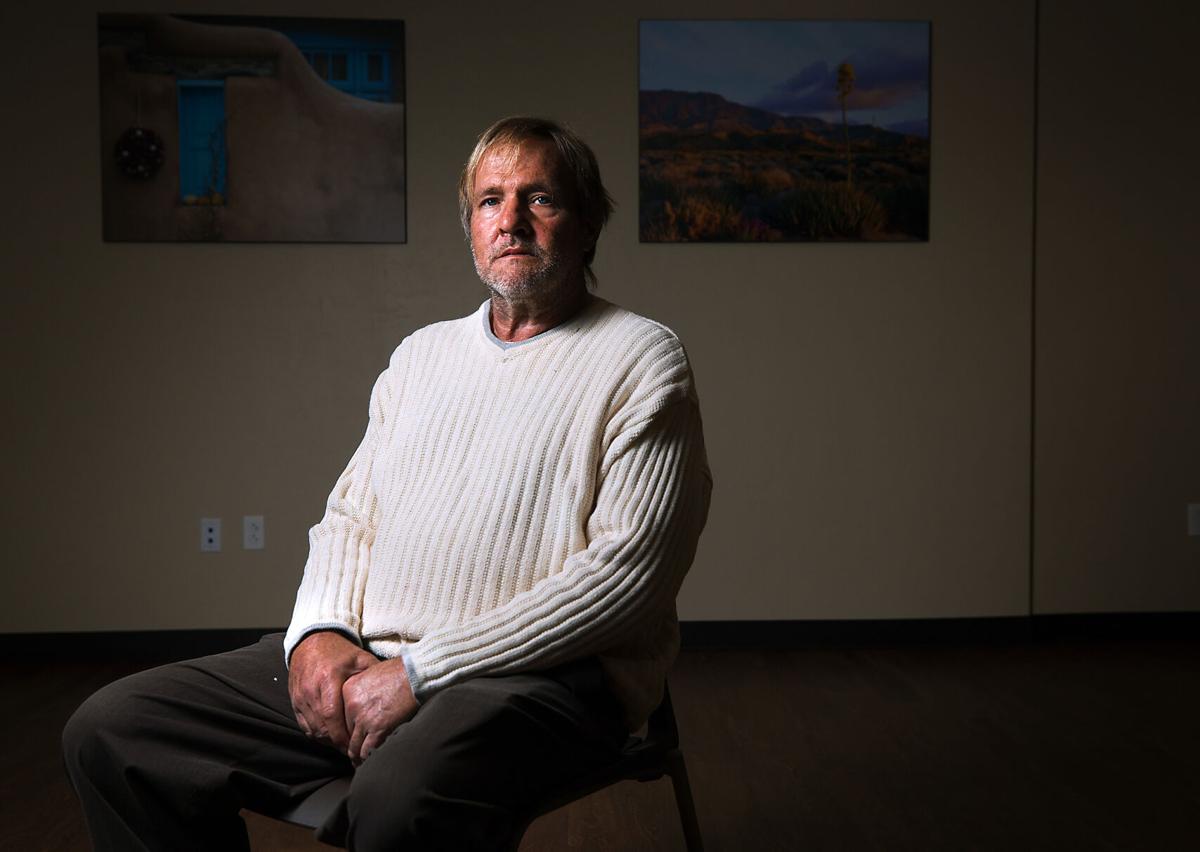

In 2018, former Kayenta firefighter Shawn Wooll was at the end of the line. He had managed to kick a 12-year methamphetamine habit the year before, and while he was sober, he still felt hopeless.

"I was miserable," Wooll, now 53, remembers. "Life wasn't getting any better, I was still living in my car, and I wasn't doing anything in recovery. I wasn't going to meetings, I was just abstinent." He had fallen out of touch with his family and lost custody of his daughter.

One afternoon he found himself on the corner of Golf Links and Craycroft roads. He parked his car along the side and stepped onto the median.

"I was debating whether to step out (into traffic) or not," Wooll says. "I know what happened now that I look back, but I couldn't walk. I tried to step forward and I couldn't."

He got back in his car and made the choice to find help. He had heard about CODAC Health, Recovery and Wellness, and decided to reach out.

"They saved my life and they gave me a life," he says. "They gave me hope."

The kind of services Wooll received at CODAC will now be accessible months or even years sooner than they might otherwise have been to hundreds of Pima County court defendants struggling with addiction. Those defendants will also be given the opportunity to avoid criminal charges.

That's thanks to a new Superior Court program — the first of its kind in the nation.

Wooll is relieved those in the program might avoid the depths he reached. And, now, as a support specialist on CODAC's staff, he's among many people there to help them.

Support from the court

The new program is an expansion of Pima County Superior Court's specialty drug court, and is a partnership with the Pima County Attorney's Office, Pima County Public Defense Services and the County Administrator's Office.

It's known as STEPs, which stands for Supportive Treatment and Engagement Program.

The goal is to divert nonviolent people who are struggling with substance use or mental health challenges away from the criminal justice system, while also getting them quickly into treatment.

The short-term, early intervention program is just the third in the country to have a pre-indictment caseload. It was modeled after one in Harris County, Texas, said Terrance Cheung, the Pima County court's division director of planning, research and evaluation. The other similar program is in Maine.

Pima County's program is the first and only one to focus on people with felony drug arrests.

In regular drug-related cases tried in Pima County, resolution through the court can take a year or longer, and most of the time the person doesn't get access to treatment until they're sentenced to probation or prison.

STEPs court drastically accelerates the process.

The program is simple: Once a person is arrested on a first- or second-time felony drug possession charge, their case makes its way to STEPs' presiding judge, Danelle Liwski.

Every Friday, the judge reviews defendants' cases to determine if they're STEPs eligible. The turnaround time from arrest to hearing is about a week, she said.

Judge Danelle Liwski speaks to a man in the STEPs program, a pre-indictment drug court, at Pima County Superior Court, 110 W. Congress St. in Tucson, on Oct. 19, 2021.

Liwski holds STEPs hearings Mondays through Fridays. At that time, the County Attorney's Office lets Liwski know if the case fits the criteria for STEPs: It must be a possession-only charge and involve no other felonies, and it must be the defendant's first or second offense.

If a person is a no-show, the state will give defense counsel several days to make contact before filing charges in the case. Liwski and others are also willing to work with people who are ill, lack transportation or face extraordinary circumstances.

Homeless people who struggle with transportation or don't have a regular means of communication are a tough population to track and engage, said Carmen Raban from the public defender's office.

"If they feel like the court is willing to work with them, they'll be willing to come back and stay in," Liwski said.

STEPs requires an in-person appearance by the candidate for the program to sign an agreement acknowledging the consequences of not completing the treatment plan. Participants say that face-time they get with the judge during the hearings has been shown to make a difference.

"Having that person of authority talking to them and saying, 'We believe in you,' makes a huge difference in their outcomes," said Deputy Pima County Attorney Amy Ruskin, who handles all the STEPs cases.

Building trust in the system

STEPs doesn't feel like regular court: Liwski speaks in gentle, soothing tones and uses positive language. When a person agrees to participate, she welcomes them into the program.

"All you have to do is complete your treatment and you're good," Liwski told one defendant during a September hearing.

From her seat behind the bench, she introduced the young man to the representative from a behavioral health agency and pretrial diversion specialist Cindy Buchler, telling him to call the latter if he had any questions throughout the process. "She's a great resource," Liwski said.

When a person agrees to complete the program, he or she is immediately screened by Buchler, who will then pair the person with one of six participating community-based behavioral health agencies for focused services based on their needs.

Buchler and the providers have on-site offices to expedite the process and avoid having to send the person to another location simply to sign up for services.

Support can range from a class teaching participants about responsibility and life skills, to in-patient rehabilitation with housing, transportation and other types of assistance upon release. That means the time a person spends in the program will fluctuate based on individual need.

"I’m not ordering treatment. I'm not going to tell them what they have to do. That comes from the experts from behavioral health," Liwski said. "I hope that gives them more trust in the system, too. "

Sonia Castro, recovery coach at CODAC, left, listens as Cindy Buchler, a STEPs diversion specialist, speaks to the judge during a STEPs hearing, a pre-indictment drug court, at Pima County Superior Court, 110 W. Congress St. in Tucson, on Oct. 19, 2021.

Participating behavioral health partners include CODAC Health, Recovery and Wellness; Community Bridges, Inc.; Community Health Associates, Inc.; Old Pueblo Community Services; The Haven; Community Medical Services; and HOPE, Inc.

The assigned agency supervises the participants and reports back if there are any concerns or issues.

"A void I couldn't fill"

Wooll's own journey to CODAC was a long one.

He says he grew up in a happy household in Kayenta, where his parents moved to take teaching jobs on the Navajo Reservation, and that his problems didn't stem from his childhood.

A self-proclaimed workaholic and adrenaline junkie, Wooll spent 20 years as a volunteer firefighter in the area, starting when he was a junior in high school and eventually transitioning to a full-time, paid job. He worked his way up to the rank of paramedic and fire chief, serving 10 years in the position.

But then, a particularly horrific 1998 incident resulted in the deaths of several children and Wooll's partner being injured in a shooting.

"I suffered PTSD really bad. After the scene, I found I had lost empathy and compassion for people," Wooll said. "Finally my boss told me, 'Sorry, you've got to get out of this.' And it crushed me."

He started to binge drink. After he woke up one morning and learned he'd taken crack while in a blackout, he checked himself in to a monthlong in-patient treatment program.

"I couldn't do firefighting anymore, it kind of left a void I couldn't fill," he said. "The things I loved to do, I didn't love to do them anymore."

The treatment didn't take. Wooll drifted away from his family and started moving around, using crack and cocaine while drinking, and eventually turning to methamphetamine.

He said he broke every rule he set for himself, and was arrested several times over the years on drug charges. He spent two-and-a-half years in prison on two convictions and tried to get treatment for his drug addiction more than once.

"Incarceration is not going to solve this problem"

On Tuesdays, Judge Liwski holds review hearings for participants who have dropped out of STEPs or are not participating in treatment, and tries to encourage them to reengage.

If it's not effective or the person doesn't show up, the state will proceed with the indictment. While it's no longer a STEPS case, Liwski will keep it on her caseload and try to resolve it faster and get the person into treatment.

"From my experience, 99.9% of people on these types of charges end up on probation," Liwski said. "So it makes sense to get them onto probation sooner rather than later, for them and the court."

STEPs launched in mid-February and is expected to include more than 1,000 low-level offenders each year.

Prior to the pandemic, roughly 2,000 felony drug possession cases were issued each year, making up one-third of the total cases issued by the County Attorney's Office.

"It's a huge chunk of the cases, but also a huge chunk of the cases that end up on probation and where treatment is really the answer to the issue," Liwski said. "I think everyone believes incarceration is not going to solve this problem."

As of Aug. 31, 314 people arrested on low-level felony possession charges were determined to be STEPs-eligible before the case was sent over to the county attorney's office for consideration, according to data obtained by the Star through a public records request.

Two-hundred of them were offered and accepted participation in STEPs, with 142 of those entered into the clinical track, meaning they require some kind of treatment for substance use or mental health.

Of the 142 who were referred for clinical services, 87 showed up to the referred provider.

And as of Aug. 31, 32 people have graduated from the program, with many of the original 200 still engaged in services.

The challenge is trying to get more eligible candidates to come to the preliminary hearing so they can learn about and accept entry into the program, Liwski said.

Getting the word out

The court is working on creating a pamphlet with more information, which Liwski hopes will help people — many of whom are afraid to come to court, she said — get comfortable with the idea.

"The public defender's office is doing more at initial appearances to speak with people about the program," Liwski said. "And we've had other judges say that people have asked about it. That's a good sign."

To date, everyone who has shown up for their hearing and been offered STEPs as an option has accepted, Liwski said.

"It's sad for me when they don't show up for STEPs, because then I have to arraign them" on the formal charges for which they were arrested, said Ruskin, the prosecutor.

The final decision if a person graduates from STEPs is made by the prosecuting office, Liwski and the defense, but they rely heavily on their behavioral health partners for input.

"With hope, anything is possible"

After that day on Golf Links in 2018, Wooll was able to get a spot in one of CODAC's transitional-living programs, a three-bedroom home that housed five men in recovery, and things started looking up.

"It was that place where I had that I knew I could put my head down, I knew I was safe," he said. "You didn't go hungry if you were there."

CODAC helped Wooll find a job at a call center, and he said the level of care he received in both his recovery and physical health was "phenomenal."

"Hopelessness is the denial of choice. I thought I had no choice, but you can choose to be better, you can choose to be happy," Wooll said. "Recovery has given me hope, and with hope, anything is possible."

He has since regained custody of his now 6-year-old daughter after taking every parenting class he could find here three years ago.

Now he teaches parenting classes for CODAC, after getting hired as a peer support specialist with the criminal justice team in August. He also works with clients in jail and helps find placements for people seeking treatment.

"This is my last career," Wooll said. "Because they saved my life."

"A model program"

One expert said the STEPS program is encouraging and addresses some of the biggest challenges in the justice system.

"People with mental health or substance use disorder need treatment urgently, but normally in the justice system it can take months or even years for cases to be resolved," said Marc Levin, chief policy counsel for the Council on Criminal Justice, which works to promote understanding of policy choices.

Sonia Castro, recovery coach at CODAC, far left, and Cindy Buchler, a STEPs diversion specialist, look over at Amy S. Ruskin, deputy Pima County attorney, as she speaks to the judge during a STEPs hearing, a pre-indictment drug court, at Pima County Superior Court, 110 W. Congress St. in Tucson, on Oct. 19, 2021.

"There's this idea that you have to get a conviction to get treatment, which I think people on all sides of the spectrum agree that shouldn't be," he said.

Levin called STEPs court the kind of solution that addresses many traditional shortcomings of the justice system when it comes to substance addiction.

"It seems like a model program that's well-designed, and given the research of what we know about intervening early, it would certainly stand to reason that this would be more effective than putting the same person on probation in the case after spending eight or nine months, and then trying to connect them with services," Levin said.

In September, STEPs court was awarded the Arizona Supreme Court's Excellence and Innovation award.

During a STEPs hearing last month, one defendant said he needed more time to think about if he wanted to participate or move forward with criminal charges. Liwski told him to take the weekend and return Monday.

"I just want you to know how important it is that you show up," Liwski told the man, as a warm smile peaked out from behind her mask. "I would like you to make it your choice and not lose this opportunity."