Visits to one of Arizona’s most intact ghost towns will soon be a thing of the past.

After more than 30 years of welcoming tourists, the private owners of Ruby will permanently close the abandoned mining camp about 75 miles southwest of Tucson on June 3.

“It’s just gotten to be too much work,” said one of the owners, Pat Frederick. “We’re all very sorry to have to close, but it’s time.”

Frederick is 80 years old, and Ruby has been in her family for most of her life.

She was still a student at Salpointe Catholic High School when her father, Tucson real estate broker and devoted fisherman Richard Frailey, recruited four partners to buy the 356-acre townsite in 1961.

“He discovered there was a lake with fish in it (on the property), and that was it,” Frederick said.

She fondly recalls family outings to Ruby to camp and fish and explore the old buildings. “It was just a casual place to enjoy,” she said.

Frederick and her husband, Howard, eventually inherited a share of the property as it was passed down through the families of the original owners.

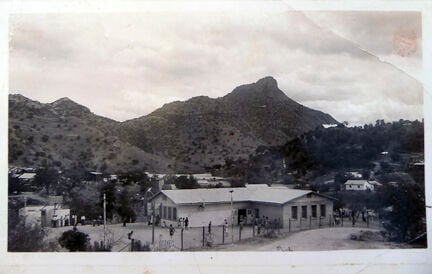

Howard Frederick hangs a sign on the museum he and his wife, Pat, established inside the old schoolhouse in the ghost town of Ruby.

Though the ghost town surrounded by Coronado National Forest land was occasionally made available to people by request over the years, Frederick said the ownership group decided to formally open the place to visitors in 1991, after researching Ruby’s history and hearing from former residents who were interested in seeing it again.

A few years later, they hosted the first of several reunions for people who had lived and worked in the town. Organizers were expecting no more than about 150 people to attend the inaugural event in 1993, but roughly 400 showed up instead.

“We had men in their 80s who had worked in the mine. It was very special,” Frederick said.

Rise of Ruby

Early prospecting in the Atascosa Mountains, west of Nogales, dates back to the 18th century, 100 years before the range would be added to the Arizona Territory by the Gadsden Purchase in 1854.

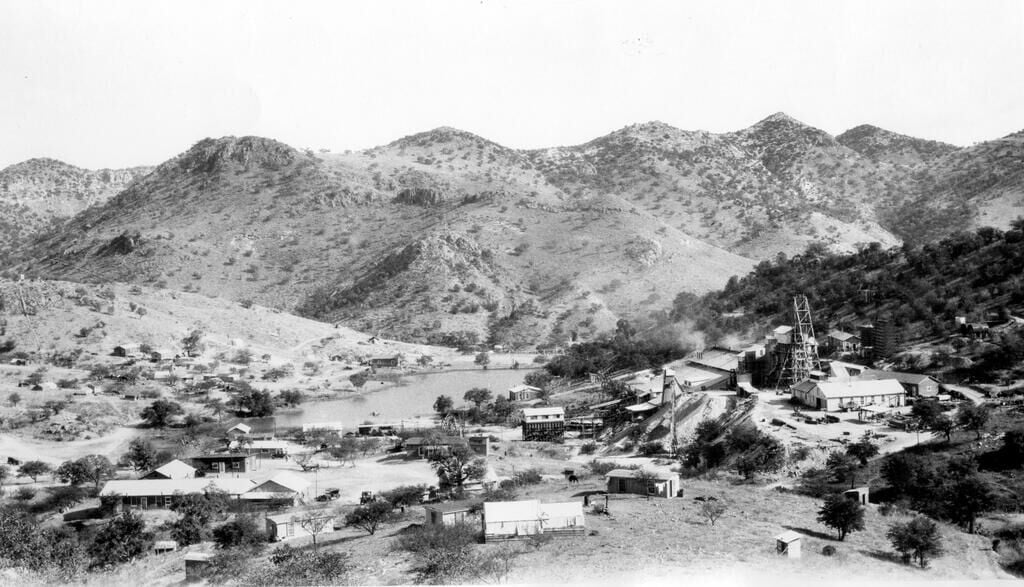

The first significant American mining activity in the area began in the 1870s, and by the turn of the century, several mills were operating in the shadow of Montana Peak.

The adjacent settlement was known as Montana Camp until 1912, when a local merchant applied for a post office for the town he christened with his wife’s maiden name of Ruby.

Before it was even a decade old, the young community was the scene of two grisly murders — the first in 1920, when brothers Alex and John Fraser were gunned down during a robbery at their general store, and the second just 18 months later, when bandits robbed and killed the mercantile’s new operator, Frank Pearson, and his wife, Myrtle.

Ruby’s most prosperous period lasted just 15 years, beginning in 1926 with the arrival of the Eagle-Picher Mining and Smelting Co.

In a photo courtesy of Tallia Cahoon, her father, mining engineer Walter Pfrimmer, holds her on a burro in Ruby, when they lived in the town 75 miles southwest of Tucson sometime in the early 1930s.

By 1930, Eagle-Picher had built a 17-mile pipeline across the Atascosa Mountains to supply its Montana Mine and the rest of Ruby with water from the Santa Cruz River.

By 1935, more than 1,200 people lived in tents, wood-frame houses and adobe structures dotting the hills.

Diesel engines supplied electricity to the town, which boasted its own medical clinic, boardinghouse, schoolhouse, Sunday school, Boy Scout troop, barbershop, ice cream parlor, pool hall and jail.

By some estimates, Eagle-Picher pulled more than $7 million worth of lead, zinc, silver and copper from the underground mine before the profits dried up and the operation shut down in 1941.

Ruby’s residents emptied out after that, leaving behind about a dozen buildings, three man-made lakes and a sun-bleached sand dune of fine-grain tailings stretching for more than a quarter of a mile.

A visitor walks across the sand dune of mine tailings at the Ruby ghost town, 75 miles southwest of Tucson, in April.

Several smaller mining ventures came and went in the decades that followed, but the town remained abandoned, save for a few hippies who squatted on the property without permission in the late 1960s and early ’70s.

Frailey and his fellow investors floated several development ideas for Ruby over the years, including as a movie set, a private club or a lakeside historical attraction. They even considered swapping the ghost town for other Forest Service property or putting it on the market for $350,000, but none of those plans materialized.

Instead, the Ruby townsite was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975, the same year Frailey died.

Back to nature

Another 18 years would pass before a concerted effort was made to preserve what was left of the town.

According to a 2004 history of Ruby, Frederick teamed up with Ned and Jim Daugherty, sons of original owner Louis E. Daugherty, to secure a $28,000 grant from the State Historic Preservation Office in 1993. Then, they recruited volunteers from the area to help stabilize and protect the crumbling buildings, with Howard Frederick supervising the construction.

That work, along with later efforts, have succeeded in saving many structures, but nature has been gradually reclaiming the rest of the isolated property, 4 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border and about 7 miles from the nearest paved road.

An opening in an adobe wall frames a patch of wildflowers at the Ruby ghost town in April.

The old mine now hosts a colony of more than 100,000 Mexican free-tailed bats that arrive each year in late spring and stay through the summer.

“They just showed up a week ago,” Frederick said. “It’s fascinating to watch them come out at night.”

Ruby’s wildness is one of the things she likes best about the place.

Once, while spending the night in one of the old buildings on the property, she said she was awakened by the roar of a jaguar as it moved through the abandoned townsite. A biologist later told her the animal she heard was almost certainly the endangered cat known as Macho B, which was the only known jaguar in the U.S. at that time.

More recently, one of the other owners stitched together a composite image showing all the animals that had walked past a trail camera on the property over the course of a single month in 2022. The picture showed a mountain lion, a bobcat, a coyote, a javelina, a gray fox, a white-tailed deer, two kinds of skunks and a family of raccoons, all crossing the same small patch of ground at different times of night.

Frederick said Ruby’s rebirth as a haven for native plants and animals received a major boost about 25 years ago, when the owners partnered with the Arizona Game and Fish Department on a fencing project designed to let wildlife come and go while keeping out stray cattle that were fouling the lakes and eating the plants down to the ground.

The sky reflects in Mineral Lake, one of three reservoirs at the Ruby ghost town. The private owners of the abandoned mining site will be closing their property to the public on June 3.

Since then, Frederick said, a thicket of trees has grown up to shade the canyon at the south end of the property, creating a new oasis for aquatic animals and other critters.

“That was not there until we fenced it,” she said. “It’s a very special place.”

Closing time

Ruby has seen its share of trouble in recent years. In 2022, a 12,000-acre wildfire burned right to the edge of the ghost town. Then last October, vandals pulled down the old front gate to the property, and several remote cameras were smashed or stolen.

But Frederick prefers to focus on the positive.

She said that since they announced the upcoming closure, a number of people have reached out to thank them for keeping the ghost town open for as long as they did.

The final decision was made in March, and the owners began advertising it on social media in April. Since then, she said, “there has been a horde” of people trying to get in to see the place before the gates are locked for good.

The school in Ruby as it looked in the 1940s.

Frederick and company plan to keep selling entry permits for single-day and overnight camping visits through their website at rubyaz.com right up until the last day. Because of the higher-than-usual volume, she urged people to be patient while their permit requests are processed.

Frederick said she is counting on the public to be respectful and stay out of Ruby after June 2. Just in case, though, the property will be monitored with security cameras, and there will be people there on a regular basis, including the biologists, historians and archaeologists who periodically will be granted access to continue their research.

Aside from the locks on the gates and the “no trespassing” signs, not much else about the ghost town is expected to change.

Frederick said there are no plans to restart mineral exploration at Ruby or otherwise develop the property. It’s going to be preserved much as it has been for the past few decades: as a nature sanctuary amid the remnants of a historic mining town.

“We are very much conservationists. We’re going to make it as comfortable as we can for animals,” Frederick said. “Not cattle, though. Just wild animals.”