Embers and smoke swirl around a saguaro with one of its arms on fire in a cell phone video captured by a firefighter in the desert northeast of Scottsdale.

The nightmarish footage is from May 18, the first night of the so-called Wildcat Fire, but it could be an ugly harbinger of scenes to come.

Once vanishingly rare, major wildfires in the saguaro scrubland of the Sonoran Desert are becoming larger and more frequent, according to a new report by researchers in Tucson and Flagstaff.

The report released Wednesday identifies a confluence of human-caused factors for the troubling trend, which threatens to transform Southern Arizona’s iconic desert landscape into a fire-prone grassland of non-native plants.

Tucson-based ecologist and lead author Ben Wilder said the Sonoran Desert has long been “largely fireproof,” but the rapid spread of invasive weeds and grasses in recent decades is covering the once-bare ground with fuel that can carry fires across greater distances.

Data outlined in the report shows two huge spikes in the amount of acreage burned by desert wildfires in 2005 and again in 2020. A number of those fires were started by people.

“It’s a really alarming transition that’s happening,” Wilder said. “We’re at an inflection point of fires becoming a much larger part of the ecology of the Sonoran Desert.”

Researchers still have a lot of unanswered questions about how forests of saguaros and palo verde trees recover after fires, he said, but based on how slowly many native plants grow, any amount of healing is sure to be a slow process.

“If it ever gets back to the desert it was before, it will take hundreds of years,” Wilder said.

And if an area is hit by waves of successive fires — a cycle of seasonal burning where there wasn’t one before — it might never recover at all.

The Bighorn fire burns in the Catalina Mountains outside of Tucson in June of 2020. A new report warns that fires in the desert are growing larger and more frequent due to the spread of invasive plants and other human-caused factors.

“The ecology of the desert that I grew up with is not necessarily the desert of the future,” Wilder said. “From my perspective, we can’t just go blindly into this future.”

Plan of attack

The new report is called “Fire in the Sonoran Desert: An Overview of a Changing Landscape,” and it’s not written like your typical academic paper.

It’s designed to be “actionable,” Wilder said. “It needs to go to land managers,” who can use the information to respond to what’s happening on the ground.

The report was published by the Southwest Fire Science Consortium with funding from the Arizona Wildfire Initiative, two efforts based at Northern Arizona University aimed at improving wildfire prevention, management and recovery.

Molly McCormick is a program manager for both the consortium and the initiative. She said the new report was developed in response to natural resource and wildfire specialists, who came to them seeking guidance after witnessing fire behaviors no one had seen before.

“It’s just happening so quickly,” she said. “People can’t circle back to what they did before, because there is no before.”

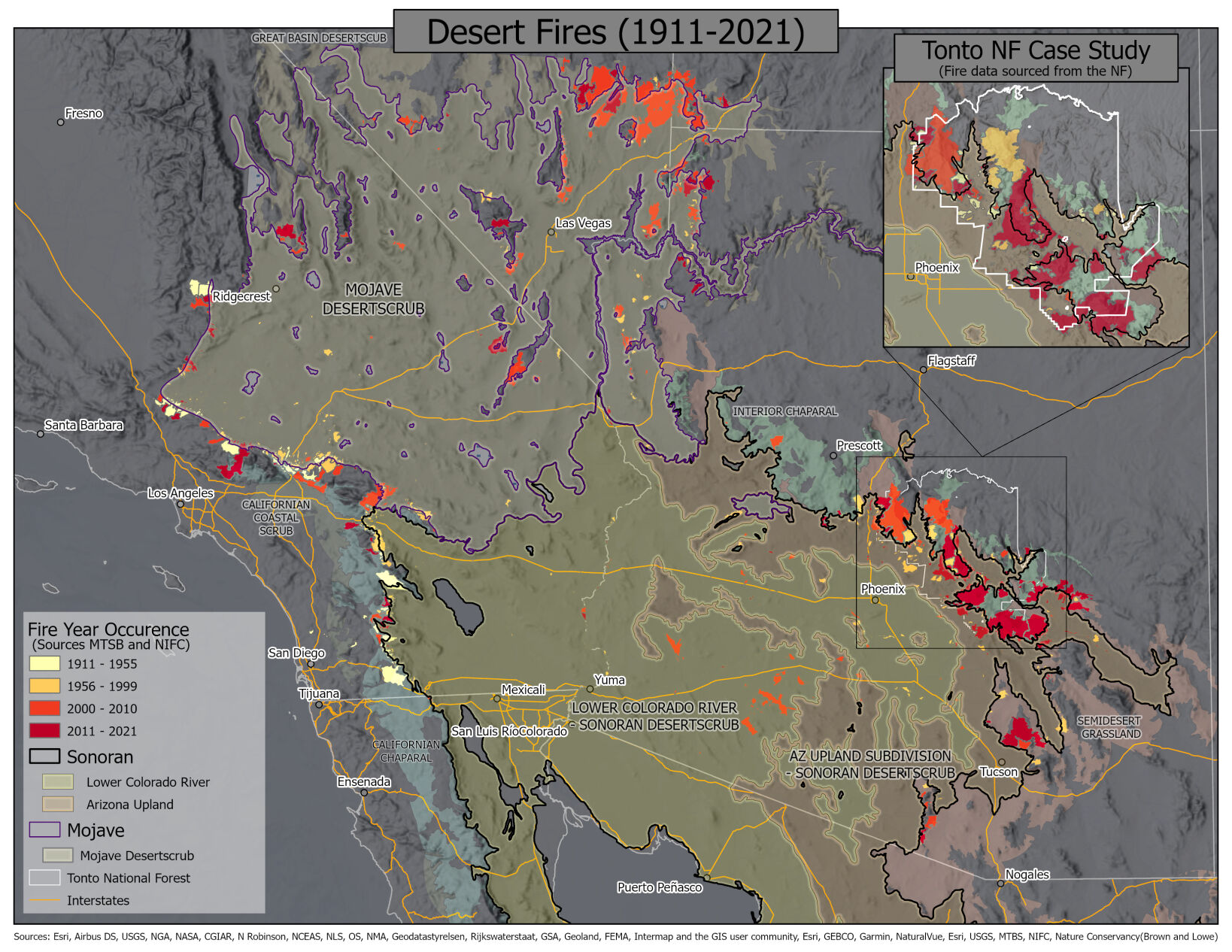

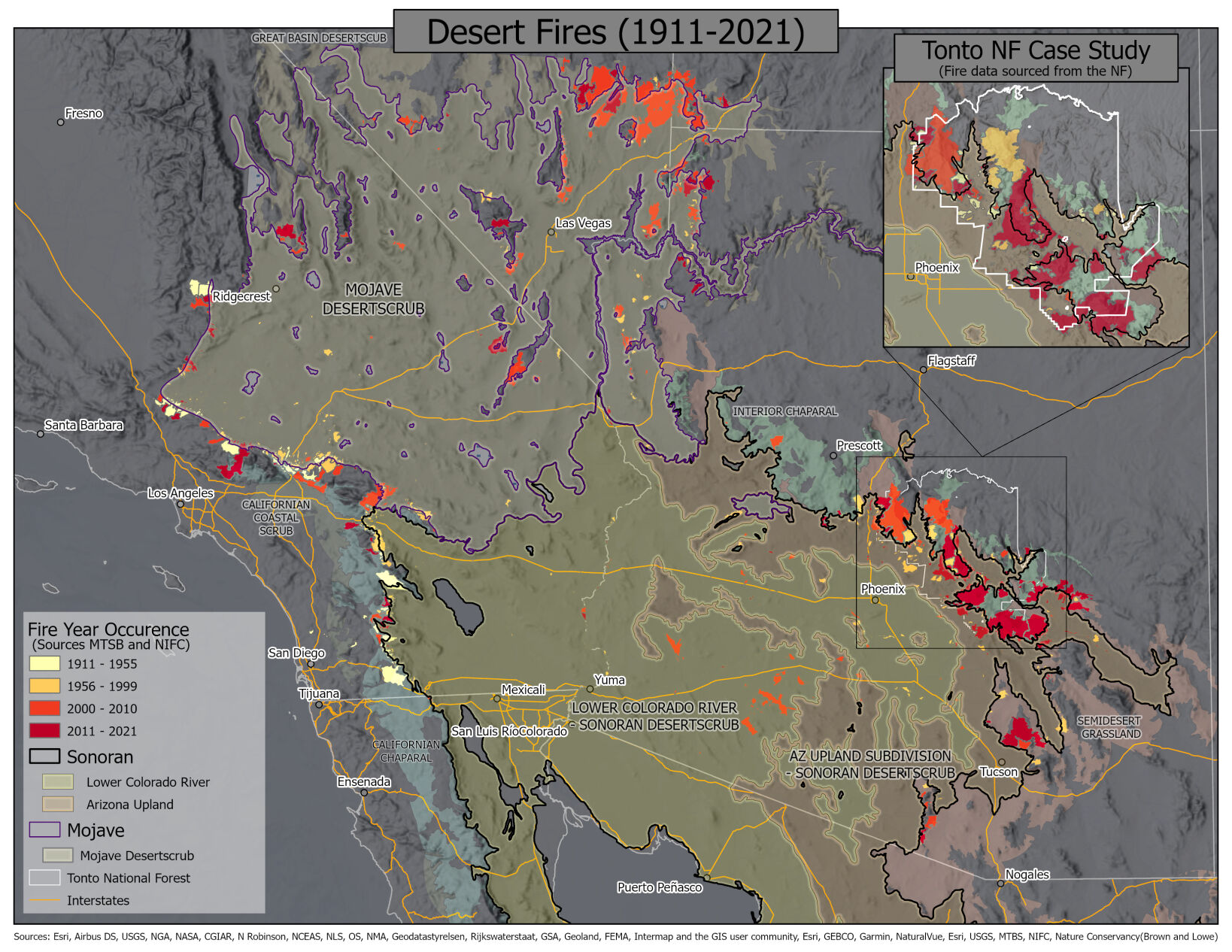

A map of desert fires from 1911 to 2021 in the Mojave and northern Sonoran deserts.

The 58-page document details a range of what McCormick called “emerging management actions,” from using hiking trails and game paths to create larger fuel breaks to designating certain areas as desert landscape “refugia” where fire should be kept out at all costs. Those might be places of ecological, archaeological or recreational importance or simply patches of pristine desert with high biodiversity that haven’t yet been overrun with invasive plants, she said.

Land managers also might need to expand the use of prescribed fires to reduce fuels in desert areas that see heavy recreational use and are primed to burn.

Desert ecologist Ben Wilder stands among saguaros that burned in the 2020 Bighorn Fire at Catalina State Park in Tucson on June 16, 2021.

Wilder said officials at Tonto National Forest near Phoenix are already experimenting with the practice around popular target shooting areas that can often be ignition points for human-caused fires.

“They’re doing controlled burns in the desert. That would have been unfathomable five years ago,” he said.

Time to act

Wilder described the report as a “synthesis” of recent research on desert landscapes and fire activity.

That includes extensive work on the aftermath of the 2020 Bighorn Fire in the Catalina Mountains by him and his co-author Jim Malusa, a research scientist with the University of Arizona School of Natural Resources and the Environment.

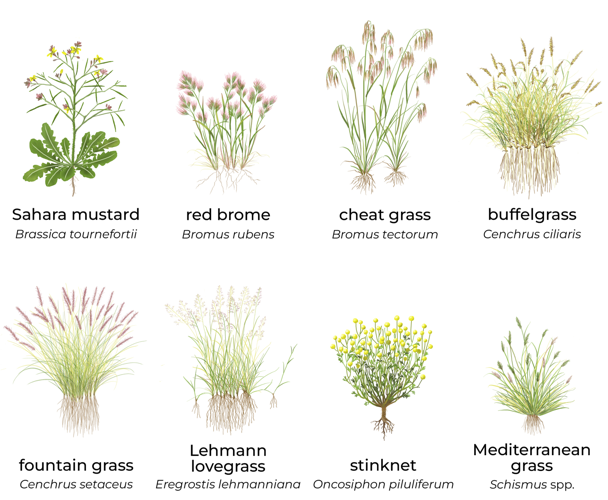

Malusa said one of the most remarkable things that researchers have discovered is the emergence of different fire regimes across the desert Southwest in response to different dominant invasive species.

In the Mojave Desert, the main fuel is red brome, a non-native winter annual. In the Phoenix area, it’s a combination of red brome and the noxious weed known as stinknet. And around Tucson, the main threat is posed by perennials such as buffelgrass and fountain grass.

This illustration shows the primary invasive plants (not to scale) that researchers say have spread into parts of the Sonoran Desert, contributing to larger and more frequent wildfires in a landscape that once rarely experienced major blazes.

“The invasive grasses are fairly patchy in most areas, but the gaps between are closing,” Malusa said. “If the strike that started the Bighorn Fire had hit further downslope on Pusch Peak, that whole slope would now be a savanna, without our green-skinned friends, the saguaro and palo verde.”

That’s why it’s vitally important to continue — and expand — efforts to slow the spread of invasive plants, the report’s authors said.

There also needs to be a wider push to prevent human-caused fires and blunt their impact, especially around growing desert cities that have seen what Malusa called “an increase in yahoos proportional to their population gains.”

“One Tonto (National Forest) employee told me of a series of roadside fires along the Beeline Highway that were ultimately the result of a single source: a man who was heading to a barbecue in Payson and wanted his charcoal briquets ready to grill, so he lit the grill before he left town and put it in the back of his pickup,” Malusa said.

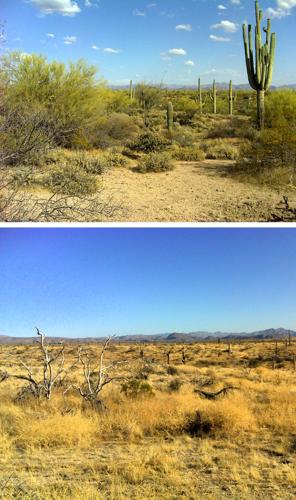

Photos taken from the same spot along the Beeline Hghway west of Phoenix in 2015 (top) and 2023 (bottom) show how the desert is changed by fire. University of Arizona research scientist Jim Malusa said desert vegetation in the Tonto National Forest has recovered very poorly after recent fires there, “and the situation for saguaros is grave.”

Though the new report documents daunting long-term problems facing our desert, all is not lost.

“There is still time to act,” Wilder said, “and the cost of action now is far lower and more impactful than it will be in just a couple years.”

Already, there are people out there doing their part, McCormick said. “There are so many volunteer efforts out in the desert that bring me so much hope. There are grandmas out there beating back the buffelgrass,” she said.

At the moment, though, land managers are worried about what the immediate future might bring.

This spring has been generally wet throughout Arizona, and “conditions are ripe for an active fire season,” McCormick said. “There is a lot of fuel on the landscape, much of it invasive, and it is drying out fast.”

As of Friday, the Wildcat Fire northeast of Scottsdale covered just over 14,400 acres. According to the national wildfire database, it was human-caused.

A map of desert fires from 1911 to 2021 in the Mojave and northern Sonoran deserts.

Besides the one in the cell phone video, it’s unclear how many saguaros have burned.