Three weeks ago, RJ Reliford II, who is a junior at the University of Arizona, was running out of time to find an affordable place to live.

He’d been living in an off-campus apartment without an official lease when his landlords decided to remodel the unit. They gave him a month to move out. In that time, he’d inquired about numerous listings. His girlfriend and family were helping him look, too. But most of the places they called require students to have someone, usually a parent, co-sign as a guarantor and that’s not an option for the 21-year-old.

“It’s so stressful,” Reliford said late last month, but “I’m just looking for reasons to keep going.”

At that point, he was four days away from his move-out date and still hadn’t found a place. His girlfriend and a few other friends said he could temporarily stay with them if nothing panned on his tight timeline. “I appreciate that,” he said. “But I just want my own stable living environment.”

Richard Reliford II, junior at the University of Arizona

Reliford’s paying his way through college with student loans, financial aid and the money he makes from two part-time jobs. But even with those resources — there’s a limit to how much undergraduates can take out in loans at one time — he’s still struggled to balance academic expenses with the costs of meeting his basic needs like food and housing the whole time he’s attended the UA.

His recent scramble to find an affordable apartment on short notice was the latest hurdle.

“When I was applying to come here, I didn’t realize how expensive the meal plans and other expenses like books really were,” said Reliford, who moved to Tucson after graduating from high school in southern California. The UA estimates the sticker price for one year of attendance for an out-of-state student living on campus, which Reliford did during his first year, is $55,650.

“Felt like a failure”

“I had to really spread out my meals. I had one good meal a week and everything else was just snacks — mostly popcorn — and maybe some Ramen noodles,” he said about his first-year experience at the UA. “The friends I made in the dorm would all want to go out to eat, but I hardly ever went because I couldn’t afford it and I was too embarrassed to ask them to pay. I hate asking for help.”

He was working at a university concession stand and didn’t have a car at the time, which made it difficult to clock enough hours to buy the food he needed.

“I would stay up all night because the hunger pangs made it hard to sleep. I was so mentally tired from working all the time, so my grades started to drop,” he remembers. “I felt like a failure.”

Reliford is far from the only college student whose immediate stressors of securing decent meals and stable housing have clouded his focus on academics and career planning.

Todd Millay, executive director for University of Arizona Student Unions, talks about the University of Arizona’s Rooftop Garden inside the greenhouse atop of the Student Union.

A statewide, national problem

A recent report by the Hope Center for College, Community and Justice at Temple University showed that out of 195,000 college students surveyed in 2020, 34% experienced food insecurity (that doesn’t just mean abject hunger, it includes scenarios like not eating enough to make food last longer, or skipping meals because a student didn’t have enough money to buy more food), 48% experienced housing insecurity (that can include crashing on a friend’s couch because a student had nowhere else to go, or not having enough money to handle a rent increase) and 14% experienced outright homelessness.

Basic needs insecurities were felt most sharply among Black and Latinx students. Women of all races and ethnicities also experienced higher rates of basic needs insecurities than men, according to the survey.

As Reliford, who is finishing up his third year as an information science and technology major, knows firsthand, those problems have major implications on student success.

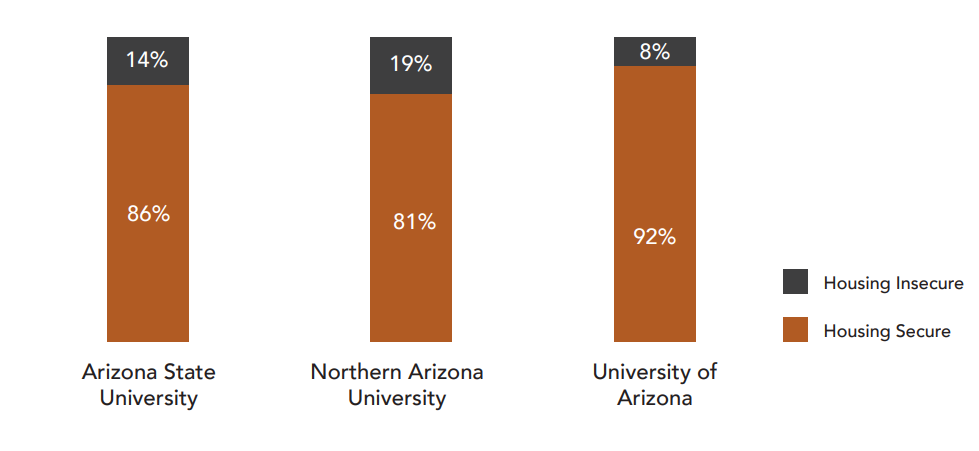

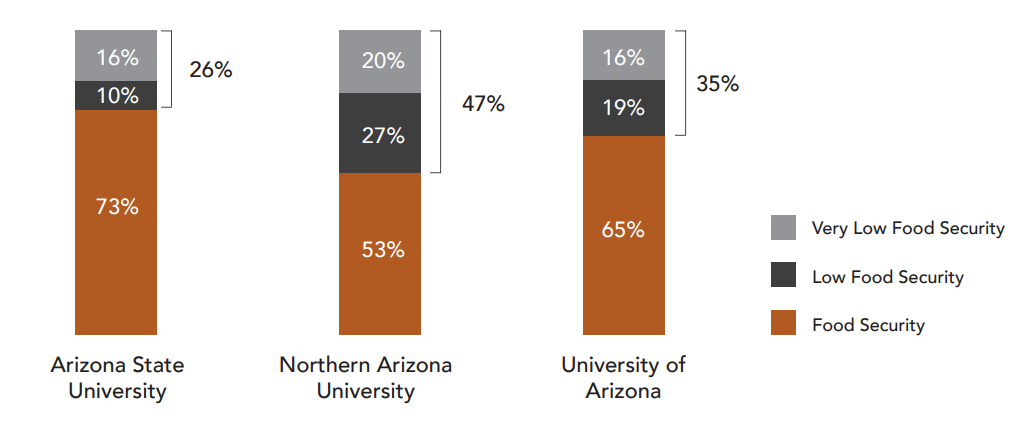

Reprint of a graphic from a 2021 Arizona Board of Regents report detailing rates of food and housing insecurity among students surveyed at Arizona’s three public universities. The report defines food security as the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire such food in a socially acceptable manner.

When students struggle to secure adequate nutrition and shelter, their risk of chronic absenteeism, withdrawing from classes and refraining from registering for courses is exponentially higher than for students who aren’t concerned about those basic needs. According to a study published in the journal Public Health Nutrition last summer, food-insecure college students were 40% less likely to graduate and 60% less likely to obtain a graduate or professional degree than their food-secure peers.

The students at Arizona’s three major universities, which include the UA, Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University, aren’t immune to any of those problems. Last fall, the Arizona Board of Regents released a report, based on surveys a working group conducted on student experiences at the three schools, detailing the extent of basic needs insecurity.

According to the report, which surveyed nearly 10,000 students during the heightened economic strain of the COVID-19 pandemic, 47% of NAU students, 35% of UA students and 26% of ASU students said they’d experienced food insecurity. NAU students also reported the highest levels of housing insecurity at 19%; 14% of ASU students and 8% of UA students said they’d faced housing insecurity.

“Serving students with the most pressing financial needs on campus requires an institutional shift from considering these issues as individual deficits and instead considering broader trends in college enrollment and cost of living,” concluded the report, which instructed each university to form a basic needs committee and produce an annual report on campus-level initiatives aimed at combating food and housing insecurity.

“Intentional changes to improve access and retention of students require additional resources to ensure students can focus on their studies rather than their basic needs.”

Resources exist, but ‘it will never be enough’

At the UA’s Tucson campus, there are already numerous initiatives underway designed to do just that.

The UA Campus Pantry, which opened as a small student-led initiative in 2012 serving about 30 people a month, now provides free groceries and other resources, like toilet paper and toothpaste, for more than 2,000 UA students and employees a month. The pantry’s full-time coordinator also helps its eligible patrons fill out the sometimes-tedious federal food assistance applications.

Although the pandemic spotlighted how many people on campus rely on a service like the food pantry, the people who have been involved with this work for years say there’s always been an astounding unmet need for food, clothing and shelter at the UA.

When the pantry first opened a decade ago, it was located in a small closet mostly stocked with a collection of donated canned goods, packs of old Ramen noodles and other non-perishables.

It’s now housed in a 3,000 square-foot grocery store-like space located on the first floor of the Student Union Memorial Center, which also includes a clothes closet where students can shop for free professional shoes and clothing.

Todd Millay is the executive director of Arizona Student Unions and dining services. When he first started working there about seven years ago, the problem of food insecurity on campus was invisible to him.

“I couldn’t wrap my head around 40,000 students coming to school here and many of them not being able to feed themselves,” said Millay, who has since overseen major expansions of the resources available to food-insecure students. “The biggest problem, though, isn’t just food insecurity. It’s financial insecurity. That includes transportation insecurity, food insecurity, housing insecurity and basic resources insecurity.”

Boxes of rice sit on a shelf at the campus pantry at the University of Arizona.

Over the past several years, the pantry has worked to acquire more substantial food donations. such as milk and eggs, from the vendors the UA already contracts with to supply its 30-plus on-campus restaurants.

In 2018, a group of agriculture students built and now staff a hydroponic greenhouse on the roof of the student union which produces some 5,000 pounds of vegetables a year that go directly to the campus pantry — a first of its kind in the country.

The university, whose campus convenience stores accept food stamps, has also started boxing up or flash-freezing uneaten food from catered campus events and preparing single-service microwavable meal boxes for distribution at the food pantry. This program now distributes more than 10,000 free meals annually.

As for what’s to come, the UA is considering instituting a similar food waste repurposing initiative at its campus restaurants, as well as a campaign to encourage customers to round up their total to the nearest dollar and funnel that money to the campus pantry.

Despite all of these efforts, Millay is realistic about the scope of basic needs insecurities on campus. “There’s something being done, but it will probably never be enough,” he said. “Unless everything is completely free I don’t know how you completely solve it.”

In addition to offering free food and clothing, the Basic Needs Center is also the headquarters for a program called Fostering Success.

It launched in 2018 and offers peer mentoring and other assistance — like helping with applications for scholarships, government benefits and housing — for any UA student who has ever been involved in the foster care system, as well as unaccompanied youths and those experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness. To date, about 5,000 students have self-identified as eligible for the program on their application for admission to the UA, but 150 have enrolled in the program.

‘A disconnect’

But the availability of these resources at the UA isn’t always known to the students who need them the most.

Although Reliford, the UA student who was down to the wire on his housing search last month, now works as the student director of the campus pantry, he didn’t find out about its existence until he’d been skipping meals and relying on caffeine to curb his hunger for months.

Reprint of a graphic from an Arizona Board of Regents 2021 report detailing housing and food insecurity among students surveyed at Arizona’s three public universities. The report defines housing insecurity to include a broad set of challenges such as the inability to pay rent or utilities, or the need to move frequently.

“I was a really involved student and still didn’t hear about the pantry and these other resources. That was shocking to me,” he said.

Instead, as he recalls it, when he told his academic advisors about his struggles at school, they suggested he drop out. “There’s definitely a disconnect between the students and higher-ups. They should at least know about the pantry.”

When Reliford finally heard about the campus pantry from a friend, it gave him access to more food and helped soothe his feelings of isolation on campus.

“It was a big support for me. I started volunteering there. It gave me a sense of belonging,” he said. “They treated me like a human being. It was one of the first places here that started to feel like home.”

Two years later, the network he’s created through the UA’s basic needs programs is still coming into play. Last month, when he was a few days shy of not having a permanent address, he got in touch with Fostering Success for help with finding an apartment.

The program was able to find a few options that didn’t require a guarantor — a big obstacle for a lot of students looking for housing — but none of those places were available for an immediate move-in. Regardless, Reliford, who didn’t realize his housing insecurity qualified him for help through Fostering Success until that week, said “it’s still nice to know I have that support.”

Then, at the last minute, he got approved for an apartment with the help of a company called Leap, which co-signs leases as a guarantor for a one-time fee.

“I was so relieved when all the paperwork went through,” he said a couple days after moving into his new place. Now, he’s got his sights set on graduating, getting a well-paying job and making a dent in his student loans. “In my freshman year I felt crappy, like I wasn’t doing anything with my life. There’s still times when I feel like that now, but overall I’m doing better.”

A lack of institutional support?

Helping students like Reliford meet their basic needs so they can focus on getting the most out of their college experience is a big goal for Dani Carrillo, coordinator of Fostering Success, and Bridgette Nobbe, coordinator of the UA Campus Pantry. But when they look at the numbers, they sometimes wonder if the UA is as serious as it says it is about helping to make that happen on a widespread scale.

The pantry costs about $370,000 a year to maintain, but the UA doesn’t directly fund that whole amount. Despite consistent yearly increases in the number of people coming to the pantry for food, the amount of institutional funding it receives hasn’t reflected those changes.

Bridgette Nobbe, coordinator of Campus Pantry and Campus Closet at the University of Arizona

The pantry gets $150,000 annually from the president’s discretion fund, which pays for the rooftop garden, one graduate assistant and food costs. It gets another $112,000 from student service fees, which funds student staffing, printing and one full-time coordinator.

The other $108,000 the pantry needs to run — it does not turn people away — comes from philanthropic donations, grants and corporate partnerships staff have to regularly apply for.

The campus closet, which serves 70-80 students a week, doesn’t receive any additional funding outside of student service fees.

Fostering Success, which receives roughly $100,000 a year from the UA to fund one full-time position, six student staff salaries and basic technology supplies, is in a similar situation when it comes to looking for outside money to make sure it’s able to help the students who ask for it.

“A lot of time is spent in the scramble of trying to keep our own jobs and create sustainability for our own jobs. That time could be better spent creating sustainable support for students,” said Carrillo, who is the only full-time employee working at Fostering Success. “We’re talking about a really elevated risk our students are experiencing and one person can only do so much. The need is vast.”

From where she sits every day, working with students who are coming to campus without the family and financial support it often takes to obtain a four-year degree, “this university has not institutionalized any of these programs, which I think communicates a pretty strong message.”

In response to the Arizona Daily Star’s questions about institutional support for these programs, Sylvester Gaskin, associate dean of students at the UA, said in an email that while the campus pantry’s mix of revenue streams meets its current demand, the university is “planning for usage of the Pantry to potentially continue to increase as more University of Arizona community members return to campus as we exit this phase of the pandemic.”

Additionally, Gaskin said, “We are examining funding to support other basic needs areas” like Fostering Success and the campus closet.

On Friday, UA officials announced they have proposed increases in mandatory fees students pay for health, recreation and other services, saying that would help pay, in part, for priorities including “expanding efforts to fight food insecurity.”

Solution: ‘Centralize’ the problem

Just as the problem of basic needs insecurity among college students isn’t unique to the UA or the state of Arizona, gaps in institutional support aren’t, either.

“Most colleges and universities are not in the mindset to think about it as their responsibility to close that gap,” said Anne Lundquist, director of learning and innovation at the Hope Center, the organization at Temple University that conducted the massive survey on student food and housing insecurity. “There’s the policy attention to it and then there’s the actual practice.”

Tomatoes grow on a vine inside the University of Arizona’s Rooftop Garden greenhouse atop the Student Union.

The Hope Center works with colleges across the country to identify lasting solutions.

“The systemic change has to have campus-wide buy-in. It needs to include people like the president and the vice chancellors for enrollment services,” said Lundquist, who pointed to Compton College and Dallas College as two examples in which top-level administrators are leading the campus response on food and housing shortages.

In most cases, however, “The actions tend to be decentralized and relegated to lower-level staff without the authority or budgets” to create systemic change.

And beyond that, she said most institutions would also benefit from centralizing basic needs insecurity initiatives within their broader missions.

“Many of the approaches tend to be focused on small numbers of students and not link it to larger institutional metrics including the larger student success and retention agenda. It’s seen as outside or separate,” Lundquist said. “If you take diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and basic needs efforts and center those into the student success and retention conversation, that will elevate it.”