Arizona and the other Lower Colorado River Basin states need to cut their water use more and faster to bring the river’s falling reservoirs into sustainability, a longtime water conservation advocate says.

The Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada need to cut total water use by 18% from their 2000-2018 average to bring Lakes Mead and Powell into a long-term state of balance, says Brian Richter.

Richter is president of the nonprofit group Sustainable Waters and a former director and chief scientist for the Nature Conservancy’s Global Water program.

His statement comes despite last year’s approval by all Colorado River basin states of a drought plan that will reduce water use some but not nearly that much in the short term.

The Lower Basin’s annual water use average was very close to 7.5 million acre-feet, the same amount the three states are legally able to pull from the river each year, Richter said, citing U.S. Bureau of Reclamation statistics.

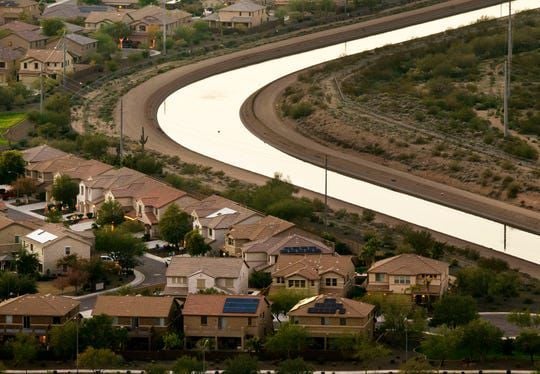

In 2019, the three states came a long way toward reaching Richter’s goal. The basin’s annual river water use will wind up at only 6.567 million acre-feet, the reclamation agency estimated at year’s end. That was the lowest annual total water use since 1986, when the Central Arizona Project wasn’t fully online yet, meaning that a lot of Arizona’s water was still staying in the river. The CAP’s canals deliver Colorado River water to Tucson and Phoenix for drinking and to farmers for irrigation.

But it’s not clear that the states will continue down the conservation path on their own. California’s Colorado River use, always by far the largest of the three states, was less than normal in part because a heavy snowpack allowed extra supplies to flow from the Sierra Nevada mountains into the California State Water Project. The project sends water from Northern to Southern California through canals.

The Drought Contingency Plan, which kicks in next year, will reduce Arizona’s take of CAP water by 12% annually as long as Lake Mead stays in the range of 1,075-1,090 feet. It ended 2019 at just above 1,090 feet.

But California is not affected by the first round of cuts and Nevada’s cut is tiny at 8,000 acre-feet, limiting the total savings the plan will achieve at first. The cuts will deepen if Mead drops to lower levels, as is expected.

Over the next seven years, the seven basin states and the feds will try to put together a longer-range plan to address the prospect of even deeper shortages on the river, which carried about 19% less water from 2000 through 2018 than it had on average during the 20th century.

Here are some questions and answers with Richter, who lives near Charlottesville, Virginia. Sustainable Waters is a global water education organization that promotes sustainable water use and management with governments, corporations, universities and local communities.

Q. Why did you look into the question of how much water needs to be saved to protect Lake Mead and Lake Powell?

A. I was frustrated. I hadn’t seen any simple statements about the status the two lakes were in. You hear things about how many feet it dropped in a year, but that’s about it. It was really prompted by another interview, in which a reporter asked ‘how much less water do we need to use to get Powell to full capacity’. I was really embarrassed that I didn’t know. I’m a numbers geek. I wanted to know how much they changed, what happened year to year, and why.

Q. You’ve been posting blogs recently that indicate Lake Powell is in particular danger because it keeps making greater than average releases to Lake Mead. You calculated that since 2000, Powell has lost an average of around 600,000 acre-feet a year. Why does this matter?

A. My real concern is for everyone that relies on this river, including the natural world. The risk of a really horrible water crisis emerging has been very understated in this basin. If we go into a repeat of the extreme drought years of 2001 through 2005, these reservoirs will tank. (Their water levels were much higher then than now, making the potential consequences of another ultra-dry spell more severe.)

That sets off quite a calamity. It means the Upper Basin couldn’t meet its legal requirements under the Colorado River Compact to deliver water to the Lower Basin. They would be forced to curtail their use. And we’d be short on hydroelectric power and in all of this I think the environment will end up getting screwed.

Q. How would an 18% cut in Lower Basin water use help the situation?

A. I have calculated that if Lake Powell had released only 8.23 million acre-feet a year to Lake Mead since 2000, Mead would be dry by now. Instead, in many of those years Powell has released 9 million acre feet, jeopardizing its future. If the Lower Basin’s use were to be cut, it would then give Mead enough water to absorb the 8.23 million releases and still stay in good shape.

Q. What drove the river’s problem home to you?

A. During 2018, the river was in critically low condition, from the summer into the fall. That time, my wife and I happened to be traveling through the West, and we went to the river upstream of Grand Junction, Colorado, a stretch called the 15-mile reach. It was precariously low. It was pretty much a trickle. I could walk the entirety of that stretch in what are normally its deepest parts. It was ankle deep in most of that stretch.

The Colorado there was down to one-tenth the level that biologists say is necessary to maintain the habitat for four native river fish species that have historically lived there.

Q. Why do you say the environment will suffer during a crisis?

A. When push comes to shove, when we are in a water shortage crisis, people get concerned they are not going to have enough water coming out of their taps. One of the last things that gets priority in those circumstances is the natural environment.

Q. How are these risks related to the way the federal government runs the reservoirs, by trying to balance the levels in Mead and Powell?

A. We’re in this situation where we are trying to balance the risks of water shortage between the Upper and Lower basins, and the rules are trying to protect both of them from running out. But the reality is that these two water bank accounts are both being overspent. If you are moving money between bank accounts and you are overspending your income in both of them, you will get in serious trouble.

Q. But the balancing of releases between the two reservoirs — isn’t this the way the system is supposed to work?

A. Don’t get me wrong. I think the bureau is doing a good job at balancing risk. But the overall problem of overconsumption is not being adequately addressed.

I’m really concerned that people aren’t reacting swiftly enough to protect us from a real disaster for both people and nature. The drought plan is a really important step but there is no active program out there to incentivize people to save water. I’d like to see programs put into place that will incentivize conservation, particularly for farmers (who use 70% to 80% of the river’s water). But I think it would be interesting to find ways to incentivize the major urban users as well to start using less water.

Q. Last year was extraordinarily wet on the river. That put off the onset of serious shortages and cutbacks until 2021 or later. It was the third good year for the river out of the last five. Could we be having a respite from the drought?

A. Multiple climate scientists are in agreement with the understanding that climate change is already affecting flows in the river system and it’s going to get a lot worse pretty quickly. At the recent Colorado River Water Users Association conference in Las Vegas, researcher Brad Udall of Colorado State University gave the best science now, that by 2050 we can expect 20 to 30% less water on the river.

Of course, we are going to have some great years. Hallelujah, I’m thankful for that. But the long-term trend is not going in a favorable direction.