On a recent Wednesday, the garden at Tucson's south-side food bank was abuzz with activity, as volunteers hauled gravel, transplanted saplings and pulled weeds in the warm morning air.

Most of the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona volunteers at the Nuestra Tierra Learning Garden that day were working on a special project: building the first of four shade huts to be erected around town, which will shelter young mesquite and fruit trees until they're mature enough to be planted in the ground.

The program is called SOMBRA, and the name has two meanings. Sombra is the Spanish word for shade, and SOMBRA is an acronym for Sonoran Mesquite Barrio Restoration Alliance.

The food bank will place the huts in parts of the city especially vulnerable to extreme heat, with a goal of increasing Tucson's shade canopy by 20,000 trees by 2030.

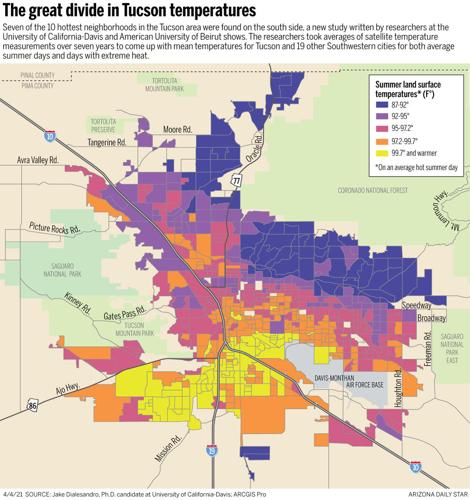

In neighborhoods with trees and shade, the air is cooler. In Tucson, seven of the 10 hottest neighborhoods are located on the city's south side, data shows.

SOMBRA is a tree-planting project at its core, said organizer Brandon Merchant, but it will also address other issues while teaching residents how to care for plants and grow their own food.

Pandemic spurs change

Merchant came to work for the food bank as its health and garden education coordinator in the winter of 2020, after his business, Southwest Victory Gardens, closed during the pandemic. A longtime volunteer and contractor with the food bank, he said the transition made sense.

Started in 2012, Southwest Victory Gardens helped people gain the skills and confidence to garden for themselves through workshops, videos and more. Merchant and others also assisted hundreds of Tucsonans with the installation of backyard gardens, he said, speaking in July at the annual agriculture conference of the University of Arizona's Water Resources Research Center.

"Growing food during times of struggle and times of need has been something we as communities have always done," Merchant said. "And folks have always grown food close to home. The closer it is to home, the more sustainable it is."

But in 2020, everyone saw the effects of the pandemic on the agriculture industry, as people found empty shelves in grocery stores. Weather-related events in 2021 disrupted food supplies again, and this year, the war in Ukraine again affected the supply chain, Merchant said.

"As one person, I couldn't do very much with gardens, so I decided to join the food bank full-time and continue that work," he said.

In the spring of 2021, Merchant started putting the idea for the project on paper after researching a similar effort in Portland, Oregon, that uses chestnuts instead of mesquite trees.

"Chestnuts offer very similar benefits as mesquite in that they're native trees that can be planted in urban settings but that provide many added benefits," he said. "The main benefit of the mesquite project is that it supplements grain agriculture."

In addition to bringing shade to neighborhoods that need it, velvet mesquite trees produce a product that can be used as a supplement to grain. Mesquite pods can be ground into mesquite flour, an added benefit of the low-water use tree, according to Merchant.

"As we started thinking about it, we started noticing that we can use these trees to also build up the shade canopy in different neighborhoods," he said. "We started tooling around with the idea of 'how can we use the trees as a food supplement or security project and also do these other parts of it, too.'"

By the time Merchant and his group were done brainstorming, they'd come up with a program that he says will address heat islands, water scarcity, food insecurity, soil health and more.

Gordan Forsyth rakes gravel in the new shade hut at the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona. Trees grown in bags are placed in the shade hut, watered for 15-20 weeks, then transplanted into the ground.

Macro and micro benefits

To advance their project, Merchant and others started meeting with city officials from the Tucson Million Trees project, an initiative driven by Mayor Regina Romero to plant one million trees by 2030 to increase the city’s tree canopy and help mitigate the effects of climate change. They talked about how SOMBRA could fit into the city's plan.

By fall, the food bank's grant department alerted Merchant to an Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management grant opportunity.

The Community Challenge Grant Program supports nonprofits and other agencies in "activities that encourage and promote citizen involvement in supporting long-term and sustainable urban and community forestry programs at a local level." The food bank was awarded a $24,750 grant in December and began ordering supplies at the start of the year.

Volunteers at the Nuestra Tierra Learning Garden, at the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona, build one of four shade huts aimed to bring shade to the greater Tucson community. This project is completely run by volunteers and the foodbank encourages the community to get involved. Video by Pascal Albright / Arizona Daily Star

Constructed out of metal piping and mesh shade screens, the huts are equipped with timed sprinklers and are large enough to protect dozens of young trees from the elements. There's gravel on the bottom to retain moisture. The design came from Desert Harvesters, which grows its plants under nearly identical setups.

The first hut is completed, with three more set to be placed in the next several months at Desert View High School, Las Milpitas Community Farm and Flowers and Bullets' Midtown Farm.

Midtown Farm's neighborhood, Barrio Centro, "is actually one of the seven of the 10 hottest neighborhoods we're talking about," Merchant said. "We're trying to target these in neighborhoods where they can have added benefits."

Those benefits include increasing the shade canopy and building up water capacity in the areas where trees are planted. Water infiltration will increase, which will help build the water table, Merchant said. In addition, leaf litter that falls and accumulates will trap and store carbon, which will eventually lead to lower temperatures.

"All of these things are sort of micro benefits of planting a tree," he said. "And there's so many other things."

If planted strategically, mesquite trees can provide shade and water runoff to other crops, including fruit and edible cacti, he said.

"Unlike corn or whatever you have to plant in a row, we can grow our flour and our fruit and stuff in one spot," Merchant said. "The idea is that you can mix things, too. It doesn't have to be just a mesquite tree. When you water this tree, you water that tree."

Building systems and capacity

Seeds for the project were donated by the University of Arizona's Desert Legume Program, which is dedicated to the preservation of legume biodiversity from arid and semi-arid regions of the world.

Volunteers prepared and planted the first batch of seeds at the start of June. Six to eight weeks later, the saplings were ready to be transplanted from smaller trays into large grow bags. From there, they were moved under the shade hut, where they'll remain until they grow to maturity.

Nuestra Tierra Learning Garden, the site of the first hut, is an educational garden located at the food bank's main branch. It features vegetables and herb gardens, a greenhouse and a chicken coop. Merchant and others use it as a demonstration garden for organic food production, rainwater harvesting and worm and compost demonstrations.

"We do a lot of cool stuff. We raise earthworms and sell worm castings and worms to folks," Merchant said. "We also provide low-cost garden materials to folks. We started a sliding-scale price structure this year and folks kind of choose whatever cost they want to pay. We've been able to kind of keep prices low even though the cost of everything has gone up."

Dozens of mesquite saplings receive protection in a shade hut behind the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona. Sonoran Mesquite Barrio Restoration Alliance will build four shade huts around town and stock them with mesquite and other trees.

The food bank's community growing site, Las Milpitas Community Farm, which will house the organization's second hut, is on Tucson's south side, near West Silverlake and South Mission roads. The 6-acre working farm is a place for neighbors to learn, connect and grow their own food. It offers community garden plots and workshops, and hosts class field trips.

During the pandemic, workshops were halted, but the food bank was able to pivot and fill other needs in the community, said garden education supervisor Victor Ceballos.

"During COVID, we were in a position where we were able to support a lot of community partners that had to temporarily shut down. Native Seeds/SEARCH shut down and the Pima Seed Library shut down, so we were the only source of seeds," Ceballos said. "There are arguments to say we should have these systems in place because if one fails, we might be able to support each other with these other ones. It's about not putting all our eggs in one basket."

As part of SOMBRA, communities will be trained on how to grow and care for their trees, as well as how to harvest and mill the mesquite pods into flour. Several local groups, including Urban Forestry of Tucson and Desert Harvesters, have offered to provide trainings.

"That's all part of it, building up the capacity of folks so they can plant these trees and care for them over the long-term," Merchant said. "Within a lot of public-maintained spaces, trees are kind of an afterthought. We want to start centering this idea that trees have many, many added benefits and they're not just nuisances."

Students play a part

Over at Desert View High School, the project will be undertaken by students in Anna Lawrie's agricultural standards class.

The course takes place over two years and includes education in plants, carpentry, and the science, business and mechanics of agriculture. Lawrie said that while students work with her, there's an ongoing thread of backyard gardening and sustainability.

"Every kid plants seeds, transplants them and has a bed in the garden," she said, adding that students also learn soil and water science, hydrology, greenhouse systems and aquaponics. "It's a good way to give kids knowledge to work in those upcoming trends and maybe get hired into the industry. They can take their knowledge from here and apply it to going to the UA or getting a job with AmeriCorps," a federal community service project that addresses local needs.

In her eighth year of teaching agriculture at the school, Lawrie said her program would be a lot different if it weren't for the food bank, where she learned skills like finding and cultivating indigenous plants and harvesting water.

"I didn't know how to do any of that. I come from a landscape background, but didn't know how to grow food in the desert successfully," she said. "The community food bank taught me those skills and I get to pass them onto students."

Lawrie said she's "so stoked" about bringing SOMBRA to campus and her students, as are her students, who learned about the program during the last school year.

"It really addresses the kids in-person, because they live in heat deserts here on the south side of Tucson," Lawrie said. "It gives a good conversation about different inequities and social justice, plus the kids learn how to be arborists for native trees."

The food bank will teach students to build the shade hut and to plant and maintain the trees. They'll also learn about shade and heat island discrepancies in Tucson and tree care, including how to properly trim and to prevent diseases.

"This relates right back to the industry, so they'll have skills to put on their résumé and hopefully can get jobs," Lawrie said. "And they can say they're part of that bigger, million tree project. Kids take great pride in being part of those larger solutions."

Goal for next year: 2,000 trees

While Merchant said the project is mesquite-centered, he said they're not going to tell people what they can and cannot do.

"A lot of people really want fruit trees, like pomegranate and citrus and stuff. Those trees are just really high water use," Merchant said. "What we tell folks is 'if you're going to do that, you plant the rain first. You either have a basin you dug with rainwater going toward it, or maybe you have the gray water coming off your laundry machine or whatever. As long as you do those things, you can definitely still get the fruit trees.'"

The goal for the first year was initially set at 2,000 trees, but the food bank encountered some supply chain and other issues and had to lower that number. There was also a learning curve with mesquite trees, as food bank employees and volunteers are used to planting fruits and vegetables.

A mesquite seed on the ground may come up after a year or so, but there are steps one can take to speed up that process, Merchant said. Volunteers had to learn to plant the seed overnight and alter its coat to encourage rapid germination, something that isn't necessary when planting fruits, vegetables and herbs.

Now that the infrastructure is in place, they can easily hit the 2,000 trees goal in 2023, Merchant said.

As part of SOMBRA, each community will get to decide what to do with the trees it grows in its shade hut. The main goal is to get the trees out into the neighborhoods and people's backyards to help build up shade and lower electric bills, and over the long-term, to help provide food security, Merchant said.

"The thing about this project is it doesn't really require a lot of investment on (the neighborhoods') end. We're really supporting most of it, so it can be as much or as little as they want it to be," he said. "There's this desire for trees and low-cost, but there's also not a lot time. People don't want to have this huge burdensome thing going on. This really helps with that because it's not too intimidating."

It's clear that green infrastructure is now a top priority for many neighborhoods in Tucson, he said.

"The community is asking us for these things," Merchant said. "We're trying to figure out simple solutions that build up community capacity that don't require huge invest on our end and that other people are really excited about and want to support, so this really falls into line with what the food bank is trying to do now."