UCLA’s ninth search for a basketball coach since John Wooden retired was destined to be a disappointment, but not necessarily a failure. It was like a golfer who needed a 66 to win the Masters but shot 70 and finished tied for sixth place.

Mick Cronin, 47 and full of energy, with nine consecutive NCAA Tournament appearances, is about as good as any Pac-12 team could expect to hire in modern college basketball.

It won’t be long until UCLA is at or near the top of the Pac-12 — maybe not year upon year, but with enough frequency that the Bruins can again rival the school’s dynamic gymnastics program for attendance at Pauley Pavilion.

Let’s be realistic. You’re not going to hire a sitting Final Four coach unless you’re Duke, Kentucky, Kansas or North Carolina.

Since the Pac-10 was established in 1978, only six Final Four coaches left their school without (a) getting fired; (b) making a stop in the NBA, or (c) stepping away from coaching for a few years such as Rick Majerus and Dick Bennett.

John Calipari left Memphis for Kentucky.

Kelvin Sampson departed Oklahoma for Indiana.

Shaka Smart left VCU for Texas.

Jim Larranaga bolted George Mason for Miami.

Lon Kruger left Florida for Illinois, but only after sinking to 17-13 and 12-16 in consecutive years.

Of that group, only Calipari has won consistently at the highest level.

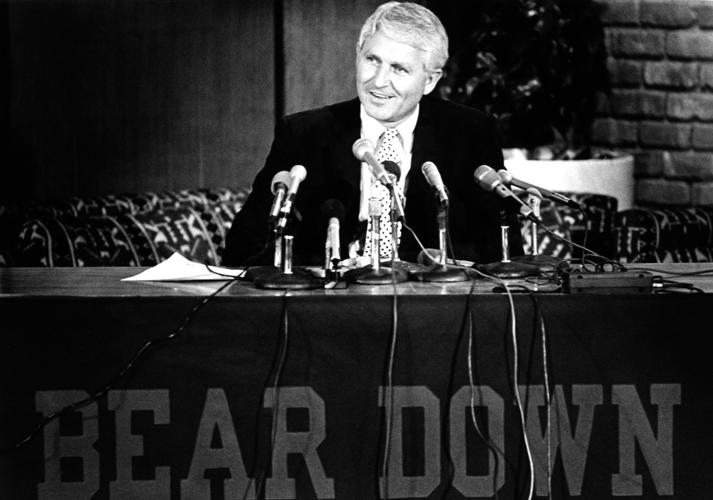

The sixth man on the list is Lute Olson, who abandoned Iowa for Arizona in the spring of 1983, and other than Calipari, sent more of a shock wave through college basketball than any other coaching move of the last 40 years.

Lute Olson signed a one-year deal at Arizona in 1983, just three years after taking Iowa to the Final Four.

There was so much serendipity involved in Olson’s move to Arizona that anything close to replicating it isn’t likely to happen again — anywhere — for another 40 years.

First, Arizona athletic director Cedric Dempsey had the conviction to aim ridiculously high. He initially targeted Olson and Villanova’s Rollie Massimino, who was on the brink of winning the national championship two years later.

Dempsey wasn’t a dreamer; he knew that Arizona had strongly supported basketball 10 years earlier, and that the league was a victim-in-waiting. Cal, Stanford, Oregon and Arizona State had dreadful basketball programs. UCLA was fading. USC and Washington State were average. That was more than half the league. Powers Washington and Oregon State were coached by men nearing retirement.

Dempsey was able to sell winning, and Olson was smart enough to sense the opportunity.

But the other variables that applied to the Olson-to-Tucson move no longer apply in college basketball.

Dempsey didn’t have to spend a fortune; Olson’s first UA contract was $65,000, although a few extras took it close to $100,000. There was no buyout of his Iowa contract. Unbelievably, under state law, Arizona was not permitted to allow multiyear contracts. Olson signed a one-year deal.

The Olson family had grown weary of living in the fishbowl in Iowa City, and the weather was a significant negative; the Olsons lived in Los Angeles for 10 years before moving to Iowa.

Dempsey was a mile ahead of the UCLA administration of the early ’80s, which surely could’ve hired Olson had it sensed the opportunity. Instead, the Bruins were going through a period in which they were hiring those with Wooden blood, such as Larry Farmer and Walt Hazzard.

Both of those men were eventually fired.

As UCLA learned in the last few months, hiring a college basketball coach at the elite level has become a fiscal jigsaw puzzle, with layer upon layer of get-what-you-can leverage and inexhaustible egos.

Best man available? Not any longer. It’s more like the lowest qualified bidder, which seems to apply to the Pac-12’s other new basketball coaches, Cal’s Mark Fox and Washington State’s Kyle Smith.

The perfect Pac-12 coach would need a mixture of qualities, including the inexhaustible dedication to recruiting of Arizona coach Sean Miller.

The perfect Pac-12 basketball coach is no longer one man, no longer John Wooden or Lute Olson. It would be a mix of qualities from the following men:

You would want Utah’s Larry Krystkowiak for his engaging nature and approachability.

You would want Washington’s Mike Hopkins because you could be confident he’d treat your son the way you would want him to be treated.

You’d want Oregon’s Dana Altman’s craft for game-planning and X’s and O’s.

You’d want Arizona’s Sean Miller for his inexhaustible dedication to recruiting.

You’d want ASU’s Bobby Hurley for his pedigree and competitive nature.

Over the last 25 years, the Pac-12 has learned the hard way about hiring basketball coaches who are too temperamental (Ben Howland), too disagreeable (Kevin O’Neill), too nice (Lorenzo Romar), too distant in the community (Steve Alford), too ready for retirement (Ernie Kent) and too in over their head (Ken Bone).

In that time, the landscape has changed so thoroughly that UCLA is no longer considered the league’s No. 1 basketball coaching job. The quality of life is better at Oregon, Arizona, Utah and Colorado. The basketball audiences in Tucson, Salt Lake City, Eugene and Boulder provide a more welcoming backdrop.

Being stuck in traffic on a Los Angeles freeway is no way to live the prime years of your coaching life.

Most of the West’s Top 100 recruits are closer to UCLA than any other Pac-12 campus, but as Mick Cronin will soon discover, the game has changed since 1975.