They lingered on the court at McKale Center, exchanging hearty hugs and oft-told stories. Coaches, ex-players, co-workers, family members, friends — all had been touched by Dick Tomey in one way or another.

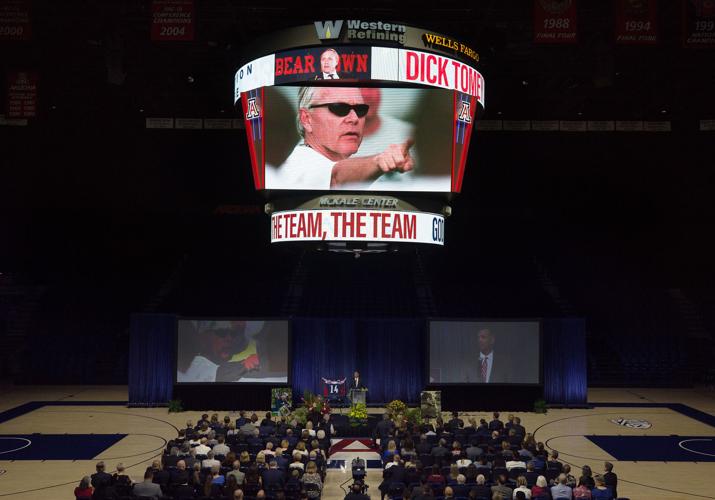

He would have loved seeing them gather and (literally) embrace this moment. Tears flowed during a heartfelt two-hour memorial for Arizona’s greatest football coach Friday morning. But as noted on the marquee, this was a celebration, not a funeral.

“When you look at the people down there, that’s what he wanted,” Tomey’s son, Rich, said about 45 minutes after the memorial. “The impact he made and the stories people tell are what keep his legacy alive. That’s what’s going on right there. That’s what will continue to go on.”

People began trickling into McKale Center at 8 a.m. By the time the event started at 9, about 1,500 had come to pay their respects, show their support and express their admiration for Dick Tomey, who died three weeks earlier at 80 after battling cancer.

Some of the attendees wore traditional mourners’ garb — black suits and dresses. Some donned blue-and-red UA gear. Others wore Hawaiian shirts and kukui leis, a nod to Tomey’s devotion to the islands.

One speaker after another ascended the stage, which sat at center court and was adorned with red, pink and yellow flowers.

Portraits of Tomey were perched on either side of the podium. One showed the retired coach waving to the crowd at Arizona Stadium; the other depicted him in his prime, in a full baseball uniform, ready to catch a high, hard one.

A framed, navy No. 14 Tomey jersey — representing his 14-year run at the UA — was positioned behind the podium. Two large video screens flanked the stage. One displayed a slideshow of photos featuring Tomey roaming the sidelines, hugging his grandchildren and posing aside his beloved wife, Nanci.

Mark Harlan was the first to address the audience. Seventeen others followed. Here’s some of what they had to say about a man who meant so much to so many:

•••

Nanci Kincaid, second from left, wife of the late Tomey, smiles at a joke during the public memorial service inside McKale Center on Friday.

Harlan, the Utah athletic director, basically grew up with the Tomey family. He considers Rich Tomey his best friend.

Harlan served as a UA team manager from 1987-92 and worked with Dick Tomey at South Florida. It was Harlan’s first appointment as the head of a program. He needed help. Tomey gladly provided it.

Harlan had witnessed Tomey’s benevolence in action.

The early part of the offseason, Harlan said, was “Dick Tomey season.” He’d spend hours on the phone, to the point of losing his voice, trying to help fired colleagues get jobs.

“If you were one of his guys, you were his guy for life,” Harlan said. “I miss him terribly.”

Then came Lisa Bravo, Tomey’s longtime assistant at the UA. Bravo recounted how every single phone conversation with Tomey ended.

"Love you, Lis,'" Tomey would say.

“Love you more, Coach Tomey,” Bravo would reply.

Then came Eli Wnek, who played for the Wildcats from 1998-2001. He recalled when Tomey came to recruit him, how he remembered everyone’s names.

“Coach noticed people,” Wnek said. “He asked. He cared. It was as if he was saying, ‘Hey, you matter. You have value.’ ”

Then came UA president Robert C. Robbins, who conceded that he didn’t know Tomey that well. But in the brief time that he did get to know him, Robbins quickly learned what Tomey was all about.

When Tomey would attend UA football games, Robbins could see how his ex-players interacted with their old coach. Robbins could hear it in their voices.

“His former players would do anything for him,” Robbins said, “because he’d do anything for them.”

Then came Ced Dempsey, the former UA athletic director who lured Tomey from Hawaii in January 1987. Dempsey was seeking a coach who could take the program to the next level. He also wanted someone who had integrity and professionalism. Tomey proved to be that man.

Dempsey recalled Tomey organizing games of capture the flag with his kids. Dempsey admired the way Tomey set the tone for the entire athletic department, how he’d attend tennis matches and softball games and lend his support to anyone who needed it.

“Dick was more than just a coach,” Dempsey said. “He was a teacher, a mentor, a family man and a man of God.”

Former UCLA and pro coach Dick Vermeil quickly discovered Dick Tomey’s passion and compassion when he hired him as an assistant in the mid-1970s.

Then came Dick Vermeil, the Super Bowl-winning coach who kept Tomey on his staff at UCLA in the mid-1970s. Vermeil didn’t have a prior relationship with Tomey. Vermeil soon discovered Tomey’s passion for football and his compassion for people.

Vermeil hosted recruits at his home one time. In the course of instructing them on techniques, Tomey backpedaled into the pool. He hopped right out and kept on going, without so much as toweling himself off.

“He signed every one of those guys that day,” Vermeil said.

Then came Ken Niumatalolo, the Navy coach whom Tomey recruited to Hawaii. A native of Laie, Niumatalolo admired how Tomey embraced the islands and represented the people there. Tomey left Hawaii as the Rainbow Warriors’ all-time winningest coach, but he did so much more.

“To measure him by wins and losses would be such a shallow reflection,” Niumatalolo said. “He drew a community and a state together.”

Then came Jesse Sapolu, the former San Francisco 49ers offensive lineman who played under Tomey for the Rainbow Warriors. Despite starting for four years and earning honorable-mention All-America acclaim, Sapolu wasn’t taken until the 11th round of the 1983 NFL draft.

“You go to the 49ers and show them you are the best draft choice they ever had,” Tomey told Sapolu.

He played for them for 15 seasons and was part of four Super Bowl champions.

Then came Pat Manley, a Tucson businessman, community leader and longtime family friend. He talked about what Tomey represented.

“It’s an idea,” Manley said. “It’s a way of life. It’s a path to greatness. It encourages all of us — the name Dick Tomey — to climb the mountain.”

Then came Kelvin Eafon, the short-yardage specialist for the 12-1 Wildcats of 1998. Eafon remembered the way Tomey made him feel loved. Tomey respected Eafon’s leadership ability and anointed him a team captain.

“He had a way of making you feel so special about yourself,” Eafon said. “He was on your butt. But family gets on your butt. He showed me how to love unconditionally.”

Former UA football player Joe Salave’a talked about the mutual love and respect Tomey and his players had for each other. “There’s a reason some of us would run through a wall for that coach —our coach,” said Salave’a on Friday.

Then came Joe Salave’a, the current Oregon defensive coordinator and star UA defensive lineman in the mid-1990s. Salave’a remembered how much Tomey believed in and cared about his players.

“Coach Tomey is what’s wholesome about this world,” Salave’a said. “There’s a reason some of us would run through a wall for that coach — our coach.”

Then came Dino Babers, the coach at Syracuse who played under Tomey at Hawaii and coached under him at Arizona. Babers spoke of the imprint Tomey left on people — about his “uncanny ability to take men and make them love each other.”

Babers met with Tomey this spring, two days before Easter. Despite his weakened condition, Tomey wanted to make sure Babers remembered what coaching was supposed to be about.

“You’re doing it for the kids?” Tomey asked him. “You’re giving back?”

“Coach,” Babers replied, “I will always ask those questions.”

Then came Chuck Cecil, the legendary UA safety whose final season, 1987, coincided with Tomey’s first. The two became great friends. Tomey had a way of bringing a team together, of somehow blending the violence of football with the ability to love his players, that has stuck with Cecil for decades.

“That’s who he is,” Cecil said. “He’s you, and he’s me. I believe the best way to honor Dick Tomey is to live our lives the way he did.”

A photo of late UA football coach Dick Tomey is projected during a public memorial service Friday. About 1,500 showed up to pay their respects.

Then came Brent Brennan, the coach at San Jose State who apprenticed under Tomey at SJSU in the mid-2000s. Brennan called Tomey his “football dad” who used “the power of encouragement” to get the best out of his players.

Brennan wrote a poem about his mentor. The verses included this one: “Making you a better man was always his goal.”

Then came Rich Brooks, the former coach at Oregon who worked with Tomey at UCLA in 1976. Brooks was privy to Tomey’s intensive competitiveness, which came out when they went for a jog (“You didn’t just go for a jog with Dick Tomey”) or when they played golf (they kept track of strokes for an entire year for a grand prize of $20).

Brooks admired Tomey’s optimism. Other coaches would despair when they lost a key player to injury. Tomey would see an opportunity.

“The glass was never half-empty for Dick Tomey,” Brooks said. “It was overflowing.”

Then came Mayur Chaudhari, assistant special-teams coach for the Atlanta Falcons who also happens to be Tomey’s son-in-law. Chaudhari recalled how Tomey would start every day by making a cup of coffee for Nanci. Chaudhari then explained that “Dick Tomey season” didn’t end when his coaching career did.

“After he retired, every day was like that,” Chaudhari said. “He could just get down deep into your soul and squeeze out every bit of goodness you had.”

Then came Angie Tomey, Dick’s daughter. She appreciated that her father always supported her, whether she was taking up rock climbing, becoming an organic farmer or taking a year off to help tsunami victims in Sri Lanka.

Angie described her dad’s passing as a “beautiful” experience. He was surrounded by his family. She thanked everyone for their well-wishes.

“He knew you were all loving him,” she said. “That meant a lot to him.”

Finally, Rich Tomey spoke. He could see the impact his father had just by peering out into the audience.

“The whole week has been an inspiration,” Rich said afterward. “It’s been overwhelming just to see the legacy he left and the lives he touched. It shows the power a coach can have … what all coaches should aspire to be.”