A few days after his 53rd birthday, Dick Tomey put on a baseball uniform and drove to the backlot behind Hi Corbett Field, carrying a catcher’s mitt and gear suitable to play in a city league game against a bunch of 20- to 25-year-olds.

Surrounded by a motley crew of ballplayers that included the UA’s groundskeeper, its golf coach, athletic trainer, sports information director, several former Wildcat baseball players and a couple of sportswriters, Tomey was comfortable in a pose as an underdog.

Late in a game that became chippy and full of macho chatter, Tomey was hit in the face by a fastball. Those from the Creative Awards dugout, Tomey’s team, some wielding baseball bats, ran toward the pitcher’s mound.

There was going to be a fight.

Momentarily dazed, Tomey gathered himself, sprinted to the mound and faced not the fearful pitcher but his own teammates.

“Get back!” he commanded. “I’ll be fine. Play ball.”

After the game, Tomey, his wife and son, Rich, the club’s pitcher, joined the team at a campus-area bar and grill, Bob Dobbs, to celebrate his birthday. He had a soft drink, and before he left to attend a movie — in his baseball uniform — I noticed two red welts on his chin. They were the outline of the stitches of a baseball.

“I wanted to make sure we didn’t get kicked out of the league,” he said. “We were only going to hurt ourselves if we got into a fight.”

Dick Tomey died late Friday following a struggle with lung cancer. He was 80. He was so much more than a football coach. The old DePauw University Tiger had a perspective on life that went far beyond wins and losses.

In early January, I sent Tomey a text message expressing my frustration that he wasn’t part of the Class of 2019 of the National Football Foundation and College Hall of Fame.

He called a minute later.

“Please don’t make an issue of this,” he said. “I’ll be fine.”

Dick Tomey once threatened to not take his team to a bowl game if the walk-ons weren’t allowed to come on the trip.

A month later, the Southern Arizona Chapter of the Hall of Fame transmitted an 18-page nomination of Tomey to the Hall of Fame office in Atlanta. It included testament to his worthiness from UA Hall of Famers Tedy Bruschi, Chuck Cecil and Ricky Hunley. Utah athletic director Mark Harlan, Tomey’s former student manager at the UA, wrote that Tomey’s proudest achievement at Arizona wasn’t beating No. 1 Washington or shutting out mighty Miami in the Fiesta Bowl, but winning the Provost Award as the UA’s best teacher. He was the first-ever coach to win the award.

“That is the kind of respect Dick Tomey had from the faculty and administration on campus,” wrote Harlan.

Tomey coached at Arizona for 14 seasons, winning more games in the 1990s than any Pac-10 team, but that wasn’t who he was. Coaching didn’t define his job. He preferred a broader concept: being a father figure, a shoulder to cry on, an advocate, a friend.

When backup defensive end Earl Johnson — a young man who grew up without either parent in his life — quit football in 1991, he moved to Las Vegas without a real plan. Tomey phoned Johnson.

“You can quit football,” he said, “but you can’t quit school.”

Johnson returned to Tucson. Tomey renewed his scholarship and Johnson finished school. For that alone, Tomey should’ve been Pac-10 Coach of the Year.

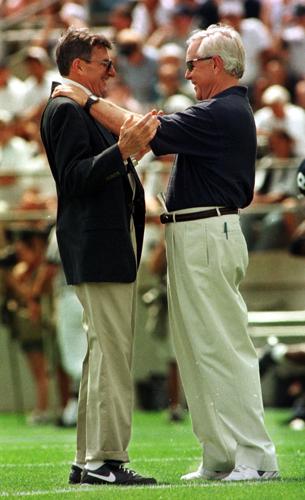

In 1999, Dick Tomey, and the Wildcats met Joe Paterno and Penn State. The Wildcats lost 41-7, but to Tomey, UA’s winningest coach with 95 victories, it was about being a mentor as much as it was about wins and losses.

After his team finished No. 4 in the nation, beating Nebraska in the 1998 Holiday Bowl, Tomey was asked if he would speak to the inmates at the Arizona State Prison in Douglas, near the UA’s annual Camp Cochise training site.

What coach of a top-10 team would do that? A two-hour drive to the most remote piece of earth in Arizona, no compensation, no TV cameras to make him look good.

Cochise College basketball coach Jerry Carrillo told me I could watch Tomey’s interaction with the prisoners, but that no photographers would be allowed and that I would be escorted from the property as soon as Tomey’s speech was concluded.

I waited in the parking lot for more than an hour on a hot summer afternoon. When Tomey finally appeared, I asked him how it went.

“It was a life-changing experience,” he said.

I told him I agreed; the prisoners visibly absorbed his speech.

“Not for them,” he said. “For me.”

Tomey was a head coach at Arizona, Hawaii and San Jose State. He also was an assistant at Kansas, UCLA and Texas.

Tomey was 60 years old. He had been a head coach at Hawaii and Arizona for 23 years. He had been an assistant coach for the iconic Bo Schembechler and at UCLA and Kansas. Yet he insisted that speaking to prisoners at the Mohave Unit of the Arizona State Prison changed his life.

When you talked to Tomey, he didn’t spend time with the details about a big win at USC or Arizona State, but about those he met along the way.

Arizona was invited to the 1990 Aloha Bowl, a homecoming game in Honolulu, playing Syracuse on Christmas Day. It was going to be all about Tomey going back to his head coaching roots, with TV cameras meeting the team on the tarmac, telling the story of Tomey’s triumph as the Rainbow Warriors coach from 1977-86.

But that wasn’t part of his plan at all. Before the trip, he sparred with the UA administration, which was trying to save money, sending a skeleton travel party to what would be a very expensive bowl game in Hawaii.

The athletic department limited Tomey’s traveling squad, informing him that 10 or 12 walk-ons would not be allowed to go.

“We’re not going unless the walk-ons are going,” Tomey insisted. “They’re as important to this team as (All-America cornerback) Darryll Lewis.”

The walk-ons made the trip.

It wasn’t a victory that gets you into the Hall of Fame, but for Tomey it was the kind of win that made you feel fortunate you could call him a friend.

Wildcats share favorite memories of their coach

'No one compared to him:' Dick Tomey's Wildcats share favorite memories of their coach

'A great man that’s willing to give people opportunities, from all walks of life'

Updated

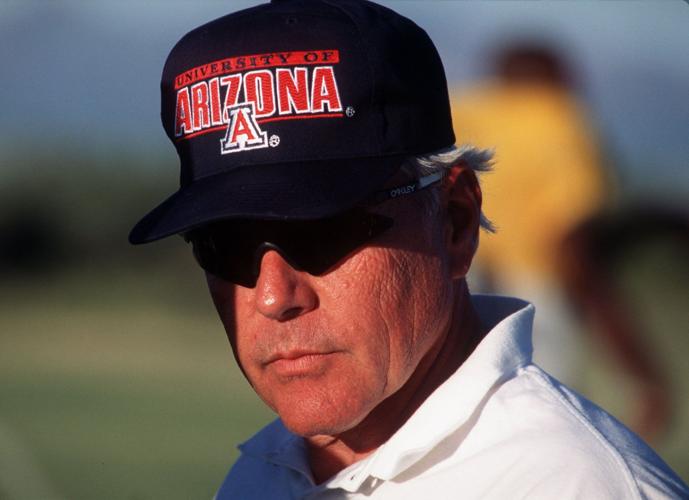

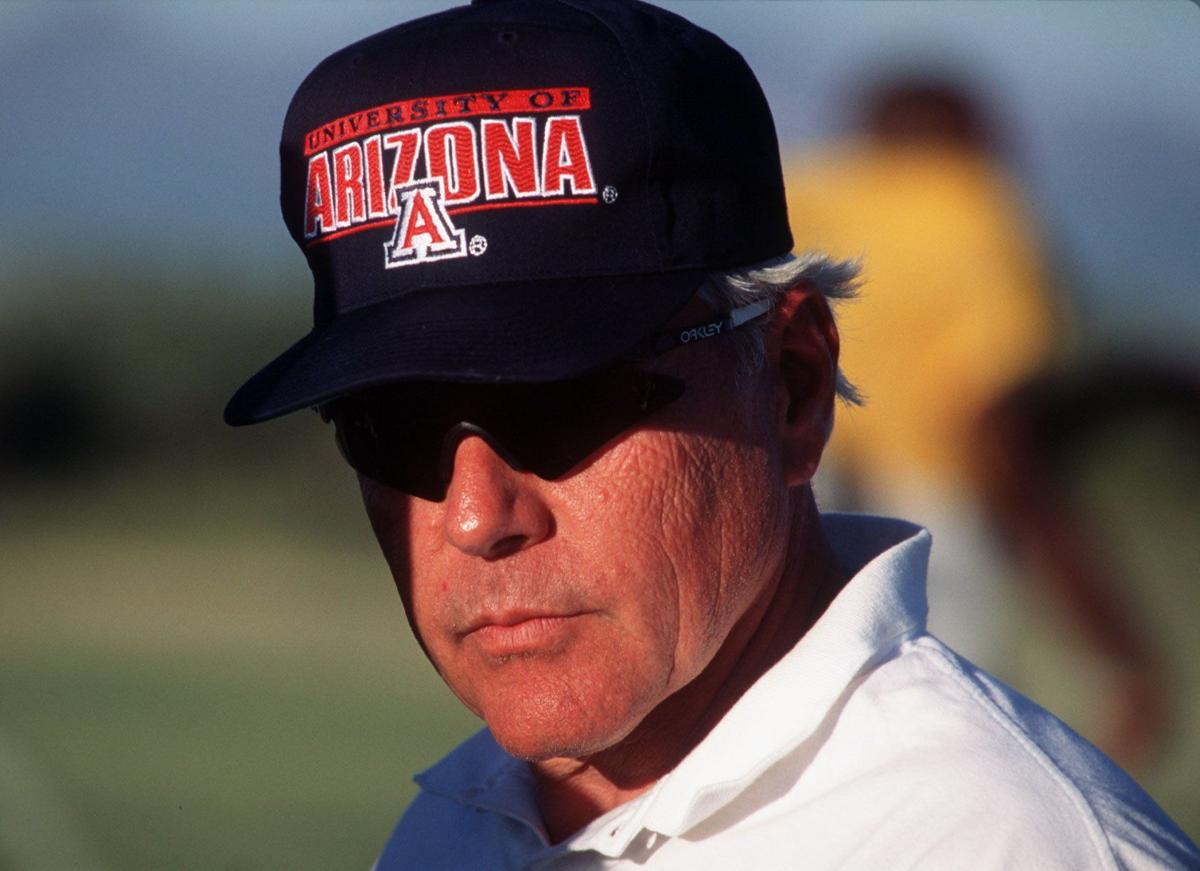

Dick Tomey beams after his Arizona Wildcats defeated Miami 29-0 in the 1994 Fiesta Bowl in Tempe.

The Arizona and college football community lost one of its own Friday night after UA legend Dick Tomey passed away at 80 following a battle to lung cancer.

At Arizona, Tomey won 95 games between 1987-2000, and 48 between 1993-98, which is considered the best stretch in program history. Tomey coached the UA's "Desert Swarm" defense and won the 1998 Holiday Bowl with an Arizona team that finished the season 12-1. With a stop at Hawaii before his time at Arizona and San Jose State afterwards, Tomey posted a 183-145-7 record over 20 years.

Known for his unique way of connecting with people, Tomey touched the lives of many and developed relationships with anyone he encountered. His UA players will be the first to tell you. Some of his players shared their favorite memories and lessons Tomey gave them at the UA and beyond.

Glenn Parker, UA offensive lineman 1988-89, recruited by Tomey out of Golden West College

Updated

Former Arizona football player Glenn Parker stretches out before a team practice with the New York Giants, Thursday, Jan. 18, 2001. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens)

Do you remember much about the recruitment process?

A: “Oh yeah. One of the things he talked about was, ‘Don’t fall in love with a coach. You’re going to a school.’ But I went to Arizona for the coaches. I went there for Dick Tomey and Ron McBride. I got offers from a lot of places. Arizona wasn’t really on my map when I started the process. It quickly became the only place I wanted to go.”

What was it about his pitch or his personality that drew you in?

A: “The first time he was in my house, we were just talking. We’re sitting in the living room with the family. He opens up a big map of the campus, and he puts it on the floor. He’s down on the floor. I’m still on the couch. He wanted me to get down on the floor with him. He was like, ‘I’m not going to be above anybody. This is who we are.’ I would never see another coach do that. It was like, ‘Wow, this guy’s different.’”

He was extremely successful here. How was he able to achieve so much at the U of A?

A: “He understood what Arizona is. He understood what Tucson is. He had come from a place at Hawaii where he build that program. He was very happy to be in Tucson. Even though he’d been at UCLA, he’d been at a lot of great places, he was happy to be in Tucson. Sometimes as fans we forget what makes Tucson … Tucson. It’s kind of like Reno, Nevada — it’s the biggest little city. Everywhere you go, you know someone. I think a lot of coaches, it becomes a steppingstone for them. Or they look at it as someplace that’ll get them back on their feet.

“Dick Tomey was happy here. Dick Tomey wanted this to be home. I don’t know that Dick Tomey looked around much, you know what I mean? He understood who we were, and he understood what type of player would fit in there. He understood who it was that he was looking for. He would get a top recruit, but he would also get some guy that nobody had noticed and knew that that guy was going to fit … the University of Arizona and the city of Tucson.”

Do you have any other favorite stories about Coach Tomey?

A: “One that endears him to every player, yet I know it would have been a source of embarrassment to him. Cal in ’89. We had to beat them to go to the Rose Bowl. We were beating them pretty well at half. Ended up losing the game (29-28). He was so angry. We were all devastated. At the end of the team prayer, he said, ‘God bless the rainbows.’ And then he swore. Openly swore at himself.

“We had never really heard him swear. We kinda laughed it off. Nobody was angry at him for it. We were all heartbroken. We all understood in the moment that he forgot where he was. The players loved him for that as much as for anything.”

Brandon Sanders, 1994-95 First-Team All-Pac-10 safety

Updated

Brandon Sanders (18), was an All-Pac-10 first-team safety twice during his career. He has the Pueblo football team off to a 2-1 start this year after a 42-0 win over Rio Rico on Saturday.

What were conversations like between you and Tomey?

A: “Whenever you left from his presence, he’d grab you by the neck or whatever, give you that smile, look at you in eye, and give you a big hug. He’ll give you a kiss on the cheek and tell you that he loved you. That’s my memory of Coach Tomey. It wasn’t beating Washington or Miami, it’s that and that resonates with me more than any ring or Pac-10 championship.”

How has Tomey impacted you as a high school football head coach?

A: “Coach Tomey said one thing at a coach’s clinic that really resonated with me: ‘Coach your players hard, but love them harder.’ When he said that, it hit me so many different ways because I look back on our time and that’s exactly who he was. He was hard on us as players, but win, lose or draw, whether you failed or were kicked out of his program, he always kept that love for you.”

Kelvin Eafon, RB and team captain on 12-1 1998 squad, scored 16 TDs as short-yardage specialist

Updated

Kelvin Eafon (38) scores the Wildcats' first touchdown in the first quarter at Arizona Stadium against the UCLA Bruins on Oct. 10, 1998.

If someone had never met Coach Tomey before, how would you describe him?

A: “A great man that’s willing to giving people opportunities, from all walks of life. The thing I always think about is all the different types of people that were on the team. We had ex-military guys. We had Samoans. We had Southern black guys like myself. (Eafon is from Dallas.) Guys from the West Coast. He brought everybody together. Never, ever did I feel any tension or anything that wasn’t (like) family around the team.”

How was he able to do that?

A: “Because he cared about the person first before the player. He for sure could coach his butt off. He had a great coaching staff. All great guys. That’s something else that I keep thinking about. Man, we had Coach (Duane) Akina ... Coach (Dino) Babers. You think about all these great coaches and men that he had us around. He just believed in people.

“One of the quotes he had was, ‘What you do speaks so loudly that I can’t hear what you say.’ You couldn’t con him with him your mouth. You couldn’t talk your way into anything with Coach. He was going to go by your character.

“One of the things I appreciated was for him to see a guy who came from basketball to give me an opportunity to come out and be on the football team, recognize that I could help the team. And then to allow me to take over the team as a captain, put my imprint on the team with my leadership. I still can’t believe that.”

Kelvin Hunter, defensive back, 1997-99

Updated

Kelvin Hunter returns a fumble against Washington State in their overtime loss 35-34 in Pullman, Wa.. Photo by David Sanders.

When did you first meet Coach Tomey?

A: “I first met Coach Tomey on my recruiting trip. I got off the plane and told him right then and there that I wanted to commit and he asked me why I wanted to commit to the University of Arizona. He then came to my house and met my dad and my dad said that’s where I need to go because he’s a man of integrity. He said, ‘That’s where you need to be because it’ll help you be a man. That meant the world to me because my dad was all about trust and if he trusted you, then that’s where I need to go.”

Barrett Baker, special teams captain, walk-on, lettered at UA in 1998:

Updated

How would you describe your relationship with Coach Tomey?

A: “Well, it’s such a cliché, but I feel like he made me who I am today. That two-year time with him, when you hear of his passing and you immediately go to look for every picture and every voicemail and every text that you sent back and forth just to see his words or hear his words … it’s just a powerful thing.

“My dream growing up was to play college football. He gave me that chance. He believed in me. It sounds kind of strange, but I swear there’s kind of a domino effect to that. When someone gives you a chance at something and then rewards it with a full scholarship, it changed the trajectory of my life. I hope that doesn’t sound too dramatic. He instills a belief in every person that he comes across that they can be somebody important.”

What’s your favorite Dick Tomey story?

A: “I was late to a meeting at Camp Cochise. Keith Smith, Mike Lucky, myself and Hadley Kilgore, we were late. He kicked us out of a meeting. We had to meet with him the next morning for discipline. Here I was, a walk-on that pretty much knew my career was over before it ever started. Two hours later at practice, I blocked a punt. He said, ‘Who was that?’ They said, ‘Barrett.’ He said, ‘Put him on the travel squad.’

“There was never any grudges held. Everything that he did was for a reason when it came to coaching. If I was late, we paid it off. If I did something great, he would pay it forward.”

Mark Fontana, offensive line, 1987-89

Updated

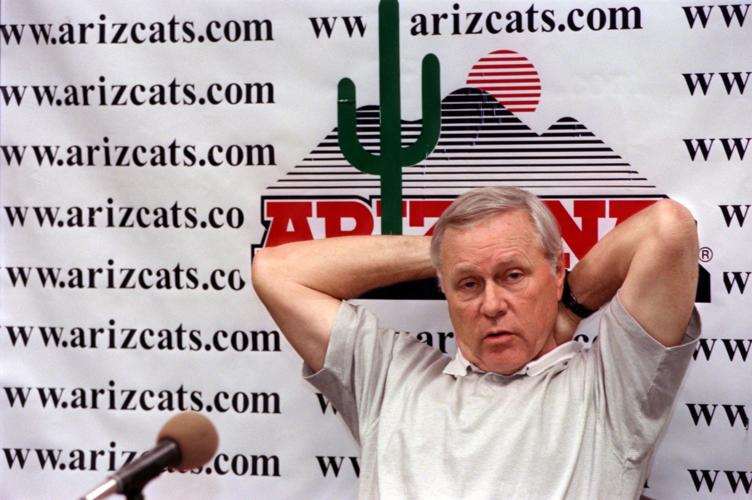

University of Arizona head football coach Dick Tomey takes questions at a press conference on January 13, 1987. Photo by Bruce McClelland/Arizona Daily Star.

What do you remember most about Coach Tomey’s philosophy?

A: “Team, baby. It was all about the team. You can’t win alone and that’s what I got from him. You have to be a team that loves each other. You have to love each other if you want to win. You can hate each other off the field and we don’t have to like each other, but when you’re out here, you have to love each other. That’s what Coach Tomey was all about.”

Was there there anything significant you took away from Tomey?

A: “I love the guy — for some reason — even more after I was done playing than when I played. Seeing how he treated people with love and respect, I looked at him more highly after I was done. Looking back on his wisdom, he was an incredible coach. Any other coaches I played for, even his assistant coaches, no one compared to him.”