Ced Dempsey was going to crash.

Arizona’s longtime athletic director and the former NCAA president lay in UC San Diego Medical Center, placed in a medically-induced coma following his 10-hour open-heart surgery in 2016. As Dempsey rested, a battle raged in his mind. He and his wife June were in trouble.

“I had dreams constantly — intense dreams,” Dempsey said. “I was taken to hell by two guys who tortured me until I was finally able to jump out, get in a truck, and drive away. Then June and I were on a plane and they made an announcement that the plane was going down and we had to get off now. I was trying to wake June, but I couldn’t wake her, so I decided to stay with her. There were a lot of people who were really mad at me for not getting off. They all got off and I stayed with June.”

Except Dempsey was fine.

“We survived,” he said. “The plane never crashed.”

Following decades spent battling health issues, Dempsey — who worked at the UA from 1982-93 and was responsible for hiring Lute Olson, Dick Tomey, Mike Candrea and others — is still ticking, even as his latest health challenge looms.

The 88-year-old is ready for another round.

Beating the odds

After nearly four decades of beating the odds against lymphoma, Dempsey continues to approach every day as an opportunity to help others. It’s fitting for a man born in Equality, Illinois.

In Tucson, he’s best known as the athletic director who brought Arizona into the big time.

Ex-UA AD Ced Dempsey, center, with former UA football star Chuck Cecil, left. Dempsey made several key coaching hires in his stay in Tucson.

Recruited at age 50 to revamp the athletic department, Dempsey made a lasting impact with his strategic hire of Olson away from Iowa and the addition of Candrea (softball), Tomey (football), Cindy Potter (diving), Joan Bonvicini (women’s basketball), Fred Harvey (track and field), Becky Bell (women’s tennis), Frank Busch (swimming and diving), Dave Rubio (volleyball) and many more administrative leaders.

Olson led the Wildcats to the 1997 NCAA championship. Tomey became arguably the UA’s most beloved coach. Candrea and Rubio are still on staff.

Concern for the welfare of student-athletes prompted Dempsey to establish the Commitment to an Athlete’s Total Success Program. C.A.T.S. was the first comprehensive student-athlete support system. Having lived the scholar-athlete life at Albion College, Dempsey created C.A.T.S. as an avenue for developing academic support and life beyond college.

Three years into his tenure at the UA, Dempsey battled cancer for the first time. Hardly anybody knew.

Half-dollar sized lumps

Dempsey was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma in 1985. It happened by chance.

The UA’s athletic director went to have his heart checked by Dr. Gordon Ewy, then head of the UA Sarver Heart Center, mentioning that he had a small but noticeable lump in his groin.

“That’s got to come out right away,” Ewy said

“Half-dollar size lumps. Do they still make half dollars?” Dempsey said.

Dempsey and his wife June chose not to tell anyone — not even their three children who were in their 20s at the time.

They found out when Dempsey’s comments about it led to articles in Tucson’s newspapers.

“They were devastated,” he said. “We didn’t tell June’s parents or the kids.”

It wasn’t long before June’s mother was on the phone, incredulous.

“Don’t you know that’s what families are for?” she said.

After a pause, Dempsey said, “I’ve been straight with them ever since.”

Cedric Dempsey in 1989

Dempsey chuckles as he describes how cancer forged a mutual understanding between academics and athletics.

Dempsey was recommended a surgeon who just happened to be on the UA’s faculty senate board. Dr. Charles Zukoski, the longtime Chief of General Surgery at the UA College of Medicine, “resented the influence of university athletics,” Dempsey said.

When it came time for his appointment, Dempsey walked into the surgeon’s office and found Zukoski sharpening a knife.

“I’ve been waiting to do this a long time,” the doctor joked.

“Over the course of my surgery and treatment we became friends,” Dempsey said.

Dempsey credits Dr. Tom Miller, former director of lymphoma at the UA Cancer Center, for his treatment success.

Through it all, Dempsey continued to work. He’d leave his McKale Center office around 5 p.m. for chemotherapy.

Then, Dempsey said, he’d go home “and sometimes regurgitate, go to sleep and get up and do it all over again.”

He continued the routine for six years.

Dempsey would occasionally hold meetings in the infusion room. Former UA associate athletic director Kathleen “Rocky” LaRose recalled seeing him hooked up to machines as foreign substances were pumped into his body. It was scary.

“One of my most vivid memories was going to his hospital room while he was discussing daily operations,” La Rose said.

LaRose, 31 at the time, admired her boss’ ability to stay calm and keep moving forward regardless of his health concerns. She did the same when, in 2002, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. LaRose also faced a rare appendix cancer in 2011. She retired from the UA at the end of 2013.

As Dempsey received treatment, June served as his gatekeeper — someone who knew what kind of day Dempsey was having, and whether he could talk with visitors.

People would ask her how Dempsey was doing. If he was well enough to meet, June would reply, “Why don’t you ask him yourself?”

On the move

Dempsey is always moving. It’s his way.

After graduating from Albion College in 1954, Dempsey took on two head coaching positions. He led the school’s men’s basketball and men’s cross country teams from 1959-62. Determined, he also earned a doctoral degree from the University of Illinois in 1963.

Over the next three decades, Dempsey accepted positions that required him to restructure underperforming sports programs.

Pacific. San Diego State. Houston. And Arizona, where he returned as athletic director in 1983 after serving as an assistant AD for three years in the 1960s.

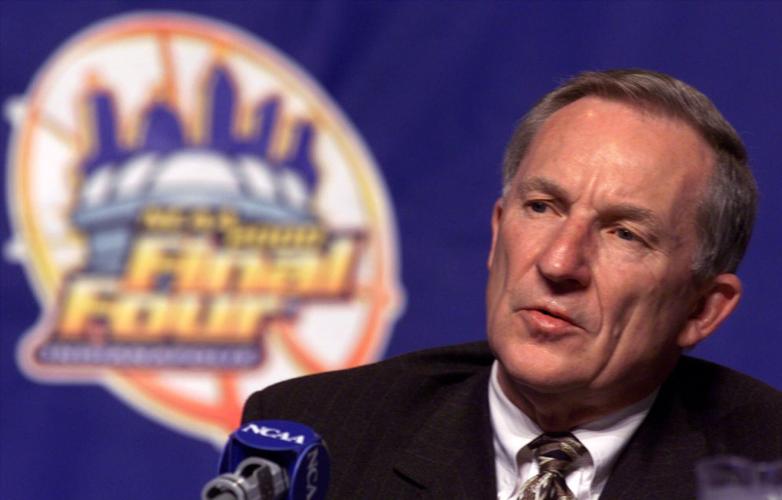

Following 11 years in charge of Arizona’s athletic department, Dempsey was named executive director and then the third-ever president of the NCAA.

After 11 years as Arizona athletic director, Ced Dempsey had a nine-year run as the third-ever NCAA president.

Based on past policy and an over-burdened bureaucracy, the NCAA required a robust overhaul. The Black Coaches Association was about to boycott the NCAA over academic standards, while Title IX for women was establishing new territory in a world dominated by men’s sports.

Dempsey resolved to improve the system rather than stroke egos. He was among the first at the NCAA to use outside experts for an unbiased perspective.

“We used outside lawyers, particularly for anti-trust lawsuits and experts from our membership who volunteered their services,” Dempsey said.

After nine years as president, Dempsey, then 71, left the NCAA. He later served as commissioner of the All-American Football League from 2007-2010. Along the way, Dempsey started his own consulting business; he continues working to this day.

Despite holding high profile positions, Dempsey wrangled with seven relocations, three bouts of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, two open-heart surgeries, a pacemaker, and the sudden loss of his son David.

David Dempsey was working as a psychiatric technician when he died in 1996. He was 37.

“When we lost David, that was the hardest of all,” said Dempsey. “David was a special, talented young man.”

All the while, Dempsey kept checking for half-dollar-sized lumps.

“When I find them,” he said, “I know cancer has come back.”

Another battle

Dempsey just knew.

After being diagnosed again with lymphoma earlier this year, Dempsey met with his doctors to discuss his treatment plan. In one exchange, he insisted that his hair wouldn’t fall out because of its color.

“It’s true,” Dempsey said. “When it’s dark, it falls out; but when it’s gray, it doesn’t.”

Former UA athletic director Ced Dempsey speaks during the dedication of Dick Tomey Football Practice Fields on Nov. 1, 2019.

His doctor asked Dempsey how he knew this. Dempsey answered: “I’ve been at this for a while.”

Dempsey started receiving new treatment in August. “This one really gets your attention,” he said.

As part of his ongoing routine, Dempsey meets regularly with a men’s group.

“They all have something wrong with them, so they don’t mind listening to your problems,” he said. “Unfortunately in the last few months four friends have passed from non-COVID-19 issues.

“That’s the trouble with getting older: People move on and they are missed.”

Over the years, Dempsey — who now lives in La Jolla, California, north of San Diego — has found creative ways to relieve stress. He and June regularly escape by watching films, reading scripture, and sharing time with friends — many of whom are Arizona graduates.

Sunsets are a time for connecting and reflection. Watching the waves of the Pacific Ocean from their front deck, June and Ced often ask Alexa to play their favorite tunes.

The voice assistant plays music by Willie Nelson, Frank Sinatra and the man Dempsey calls “The ‘Sweet Caroline’ guy” — Neil Diamond.

The Dempseys were blaring The Village People’s “YMCA” recently when they noticed something across the street. Six young girls were dancing with them.

“Dancing On our deck to ‘YMCA’ at 88 is almost as much fun as making a hook shot at 18,” he said.