After listening alongside a rapt audience to Julius Erving recount the story of his remarkable life, I came away with this conclusion:

None of what Dr. J has accomplished was as easy as he makes everything seem.

Michael Lev is a senior writer/columnist for the Arizona Daily Star, Tucson.com and The Wildcaster.

Erving will turn 75 next month. He retains the elegance with which he played basketball. As Magic Johnson once said of Erving’s most iconic move — his one-handed, gravity-defying reverse layup against the Lakers in the 1980 NBA Finals — Dr. J played as if he were “walking in the air.”

But as Erving revealed during “An Evening with the Doctor” on Thursday at Palo Verde High School — the latest in the African American Museum of Southern Arizona’s “Fireside Chat” series — he is a grounded person who came from humble beginnings.

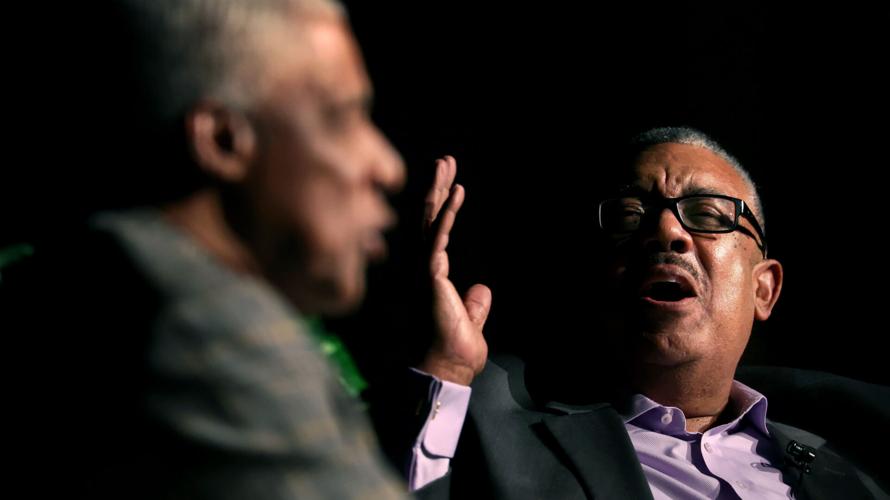

Erving shared the stage inside the PVHS auditorium with former teammate, longtime friend and AAMSAZ co-founder Bob Elliott. As Elliott joked afterward, he had a tough job: “All I had to do was lob softballs and get out of the way.”

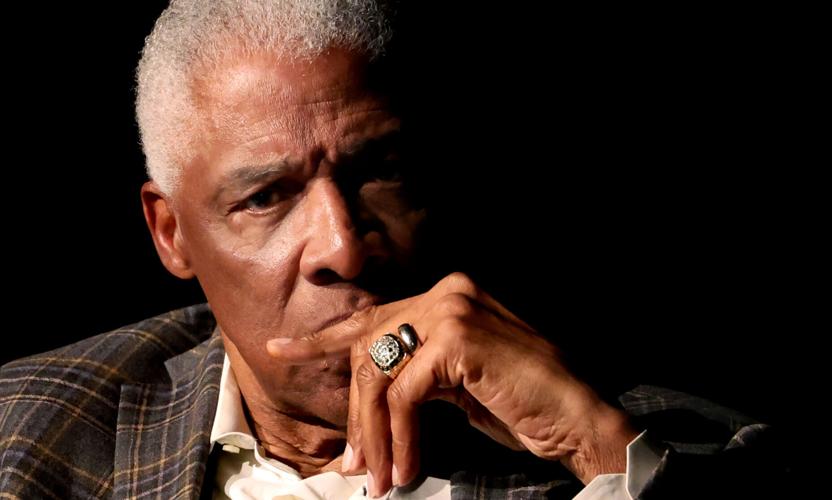

NBA and ABA great Julius “Dr. J” Erving mulls over a question from his former teammate Bob Elliott at the African American Museum of Southern Arizona’s “An Evening with the Doctor” at Palo Verde High School on Thursday, Jan. 16, 2025.

Erving still knows what to do with a lob.

Asked to tell his personal oral history in the spirit of some of the exhibits at AAMSAZ, Erving delivered a string of tales that would have earned perfect-score 50s if they were being judged like the dunk contests he practically invented.

He began by talking about his childhood. The last surviving member of his immediate family of five, Erving grew up in a housing project in Hempstead, New York, in the 1950s and early ‘60s. His parents split up, leaving his mother, Callie Mae, to take care of Alexis, Julius and Marvin.

The state of New York wouldn’t acknowledge the teaching certificate Callie Mae had obtained in South Carolina, so she did “domestic work” at a dental office and people’s homes, her middle child said.

“She just did what she had to do to get by,” Erving proudly recalled. “She was my hero.”

Callie Mae eventually became a hairdresser. She always insisted that Julius introduce himself by his given name, not Dr. J, a nickname born as an inside joke between himself and a teammate in high school.

“That goes back to Mom,” Erving said. “’We gave you your name, and I want you to use it. All this “Doctor” stuff, what’s that all about?’

“Then I got a couple honorary doctorate degrees. I said, ‘Aha, now I can use this. There’s truth in advertising.’”

As a youngster, Erving played basketball at Campbell Park near his home. Per a video shown during Thursday’s chat, it was too cold to play one day. So Erving and his friend, Archie Rogers, went to a gym to see if they could join a Salvation Army team.

The team’s young coach, Don Ryan, who’d later become Hempstead’s mayor, accepted the pair of 12-year-olds — even though they were Black and that area, at the time, was all white.

“Nobody on the team but me and Julius was African American,” Rogers said in the video. “But we were children, and we didn’t feel the racism.”

They became a team that would pile into the back of a station wagon to travel to games. The lessons Ervin learned from the Salvation Army — to “live not for ourselves but for others” and to “carry the books and the ball” — stuck with him for the rest of his days.

Bob Elliott, right, chats with his former teammate ABA and NBA great Julius “Dr. J” Erving at the African American Museum of Southern Arizona’s “An Evening with the Doctor” at Palo Verde High School on Jan. 16, 2025.

“If you didn’t get good grades,” Erving said, “you couldn’t play.”

The Ervings moved to the Roosevelt neighborhood, where Julius attended high school. He played baseball and football as well as basketball, but hitting was hard and the heavy football cleats suppressed his ability to jump.

“Black man can’t jump,” Erving joked. “That’s a problem.”

So basketball it was. But back then, Erving was 6-3½, 170 pounds. He wouldn’t grow into the prototypical small forward — 6-7, 210 — until college.

Erving said he had about six offers. He attended UMass. Dunking was banned in college basketball at the time. Can you imagine? Sorry, Doc: No dunking. That’d be like telling Hank Aaron he couldn’t hit the ball over the fence or Randy Moss that he couldn’t cross the goal line.

It didn’t matter. Erving averaged 26.3 points and 20.2 rebounds over two seasons. He got an offer from the NBA’s rival league, the ABA, to join the Virginia Squires after his junior year. They would pay him $500,000 for a four-year contract with the payments spread over seven years. It was an unimaginable sum for someone who’d grown up in a housing project.

“I didn’t have to think too long,” Erving said, drawing laughter from the crowd of about 1,000 at PVHS. “I just had to get her blessing.”

That would be Mom. She made him promise he’d finish school. He eventually did, walking with the class of 1987.

“She was so happy,” Erving said. “If you say you’re gonna do something, do it.”

Erving’s move to professional basketball came amid tragedy. Marvin, his younger brother, contracted Lupus and died when he was 16 years old. Erving was 19 at the time. His father already had passed. Although his mother had remarried, Erving felt as though he needed to be the man of the household. He carried their spirit with him on the court.

“Anytime I went mano a mano against anybody,” Erving said, “it was three against one.”

Erving dominated in the ABA, playing an above-the-rim style that had even the greats of the time in awe. He was a pivotal figure in the ABA-NBA merger. The Philadelphia 76ers bought Erving’s contract from the New York Nets. The rest was history. Erving became an 11-time NBA All-Star, an MVP (1980-81), a champion (1982-83) and a Hall of Famer (1993).

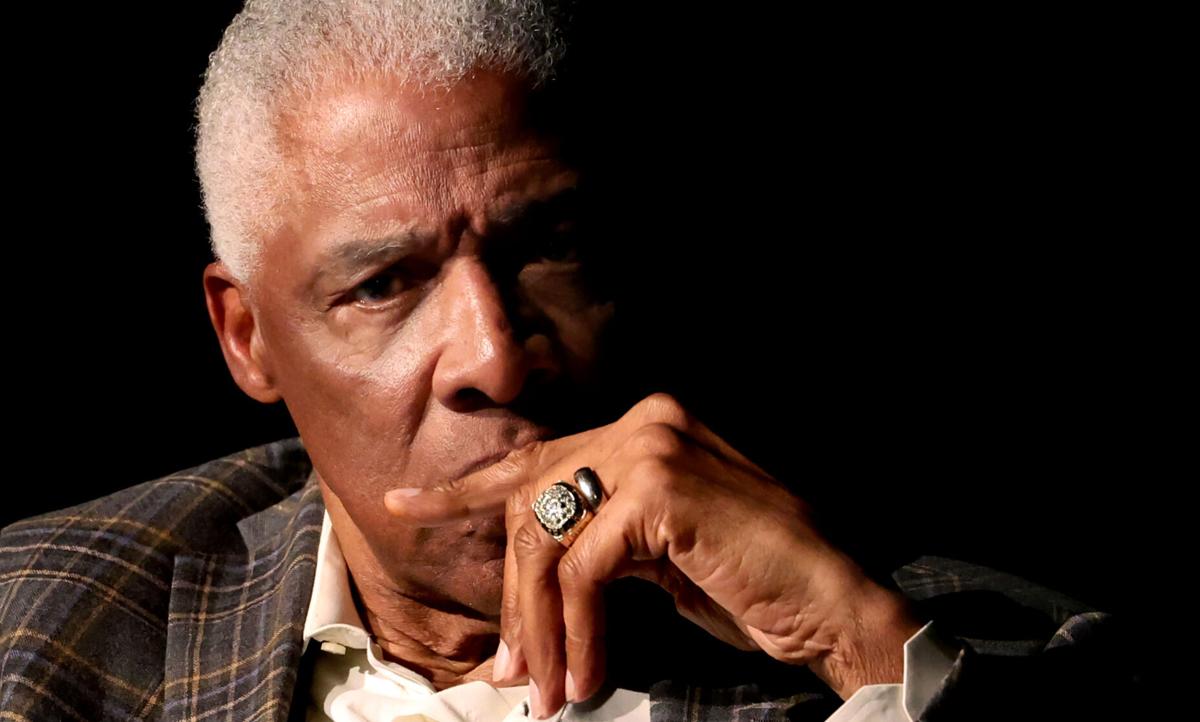

NBA and ABA great Julius “Dr. J” Erving relates an anecdote about growing up while onstage with his former teammate Bob Elliott at the African American Museum of Southern Arizona, Thursday, Jan. 16, 2025.

Toward the end of his playing career, Erving would lose his sister, Alexis, to colon cancer. She was 36. Julius was 34.

So even though he enjoys reliving the glory days, you can understand why Julius Erving prefers to look forward.

“I’ve always wanted to keep the carrot out in front of me,” he said. “My carrot is, I’d like for the best day of my life to be ahead of me as opposed to behind me. I try to orchestrate that. Sometimes it feels a little bit like a pipe dream. But to have that feeling, wake up in the morning, ‘This could be it — best day of my life.’ I’ve had some good days. I’m not conceding.

“Good things will happen to people who allow it to happen. Look for that best day in your life to be tomorrow, not yesterday.”

Doctor’s orders.