Two Tucson-based artists, Navajo tapestry weaver Barbara Teller Ornelas and Tohono O’odham poet Ofelia Zepeda, were named 2023 USA Fellows and will each receive an unrestricted $50,000 cash award from United States Artists, a Chicago-based arts funding organization.

Ornelas, 68, is an accomplished fifth-generation master weaver raised in the famed Two Grey Hills on the Navajo/Diné Nation, near Newcomb, New Mexico.

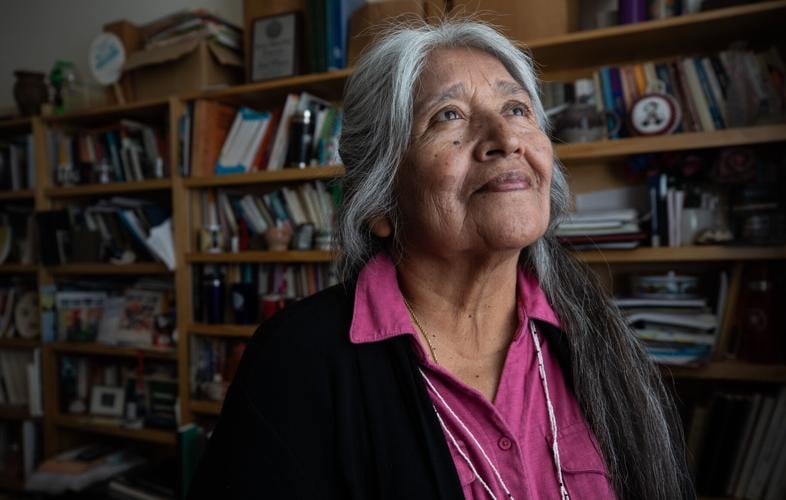

Zepeda, 68, has roots in the rural town of Stanfield, Arizona, and is an author, regents professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona, an affiliate faculty in American Indian Studies and director of the UA American Indian Language Development Institute, which works to revitalize endangered languages, and serves educators, researchers and activists.

Ofelia Zepeda, professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona, has taught many Tohono O’odham educators to teach the O’odham language to students and to develop the language in their communities.

“The award honors their creative accomplishments and supports their ongoing artistic and professional development,” according to a news release from United States Artists. This year, 45 fellows across 10 creative disciplines, were recognized across the country. Ornelas received a fellowship in traditional arts and Zepeda received a fellowship in writing. The other disciplines were architecture and design, craft, dance, film, media, music, theater and performance, and visual art.

Ornelas said the cash award will allow her to take some time off. “I put an ex-husband through pharmacy school, and two children through college. I never had a break. This money will let me slow down a bit and buy new equipment for weaving. I am very grateful.”

Zepeda said the award will enable her to focus on producing more contemporary poetry in O’odham with hopes of getting it published. She also said she has book projects that she wants to finish.

Master weaver

Ornelas remembers weaving at age 5, learning from her mother, Ruth Teller, and her grandmother, Nellie Teller. In the family home in Two Grey Hills, New Mexico, Ruth weaved on her loom in the living room while Ornelas and her two sisters weaved on their looms nearby. Ruth taught her daughters basic weaving using white, brown and black wool in the style of Two Grey Hills weaving. Ornelas learned the stories, songs and prayers that are integral to weaving from Nellie.

Nellie taught the girls how to pray before they started weaving, and the songs while working the loom, finishing the piece and taking the weave off the loom. Nellie passed her knowledge to Ornelas before she died in 1968, nearing the age of 70. Ruth, who died in 2018 at age 88, also taught Ornelas everything she knew about weaving.

Barbara Teller Ornelas is an accomplished fifth-generation master weaver raised in the famed Two Grey Hills on the Navajo/Diné Nation, near Newcomb, New Mexico. Video by Carmen Duarte/Arizona Daily Star.

Ornelas said her mother and grandmother were master weavers and taught her what her family is known for — tapestry weaving. These pieces are hung on walls, and Ornelas sold many pieces at Two Grey Hills Trading Post where her father was a trader and worked the store for more than 35 years.

“I have been teaching Navajo weaving for over 23 years,” said Ornelas, who along with her younger sister, Linda Teller Pete, teaches classes at the Heard Museum in Phoenix and also at Idyllwild Arts Academy in California, in the mountains above Palm Springs.

“I teach students everything I know, and share certain songs and prayers. But, my songs and my prayers are personal and I keep them to myself. The only ones who have heard my songs and prayers are my children and my grandchildren,” said Ornelas while sitting near her loom in her studio at her midtown home. Boxes of wool that she spins are in the studio. She mentioned she learned how to shear sheep at a young age at her grandmother’s house.

“My grandmother lived in a hogan, a round space, and she had her loom in the living area. I would sleep under her loom when I was visiting her,” said Ornelas with a smile while recalling the special moments in her childhood. Her grandmother lived in White Rock, New Mexico.

When Ornelas was older and it was time to go to grade school, she was sent to Toadlena Boarding School in New Mexico, about 60 miles north of Gallup. She continued her weaving while in boarding school, missing her family for months on end. When she returned home in the summer, she weaved some more, learning more about technique and design work from her older sister Roseann Teller Lee. Her father would take Ornelas and her sisters to Two Grey Hills Trading Post to sell their pieces. The family also traveled to Farmington and Gallup where they bought their school clothes for the year. After grade school, Ornelas went to Aztec High School, a public school in New Mexico.

Ornelas moved to Phoenix when she was older and began selling her work to galleries. Gallery owners then told her that her weavings were high quality weavings that should be sold to museums and private collectors. In 1979, she sold a piece to the Heard Museum and gallery employees groomed Ornelas into the artist she is today.

It was at the Heard Museum that she learned about the use of colors, and she began weaving with reds, blues and pastel colors. There are over 80 different styles of Navajo weaving.

Barbara Teller Ornelas works on a wool tapestry at her home in Tucson.

“A lot of my weavings are inspired by old pieces. I get inspired by paintings, sunsets — especially Arizona sunsets. Right now, I am working on a piece with different shades of purple, magenta, maroon, greens, yellows, pinks and blues. It reminds me of the Arizona sunsets, but with a purple hue,” said Ornelas as she looked at the piece on her loom.

“There were a lot of workers at galleries who believed in me and they taught me how to sell my pieces,” explained Ornelas who was guided on where to go and who to see. In 1985, she traveled to London to the Museum of Mankind, which is part of the British Museum, and Ornelas was featured in the American Festival. The festival highlighted diverse communities, including jazz musicians from New Orleans and Chicago, and Native American artists. She sold a tapestry weaving to the Museum of Mankind.

Her pieces are in countless collections, including the Denver Art Museum and the Eiteljorg Museum in Indianapolis. She has authored books on Navajo weaving and is an advocate for Navajo weavers. She lectures and participates in cultural exchanges through the U.S. State Department, traveling to Peru, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

The weaver’s smaller pieces sell for $1,500 and large pieces — 5-feet across and 9-feet long — sell for thousands of dollars. She and her sister sold a piece to a private collector for $60,000. The piece won Best of Show at the Santa Fe Indian Market. Ornelas can invest months in completing smaller tapestries to over a year when weaving big pieces.

“I love looking at the old collections in different museums. Navajo women 100 years ago were great weavers, and did not work in a comfortable studio sitting on a chair and having great light. This makes my work easy compared to what they had. I am inspired by their legacy, tenacity, creativity and their brilliant designs. I can pass on their legacy to my students and my children and grandchildren,” Ornelas said.

Beauty in language

The award-winning Zepeda didn’t grow up writing poetry.

It was an O’odham language class that she was teaching at the UA that sparked the writing bug.

O’odham students were in the class to learn to read and write their language. “Some of the students were traditional O’odham singers, and when I saw their songs in print I would call it poetry. The O’odham songs became a collection of reading materials,” Zepeda said.

She began writing her collections in O’odham and English, and her poetry includes the desert, summer rains, family life, and wise older women who made an impression. Among her books are “Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert“ and “Where Clouds are Formed.”

It’s no surprise that she draws from nature, having grown up in the community of Stanfield, enjoying the rural, open spaces. One of the nearest cities is Casa Grande.

Her father, Albert Zepeda, and her mother, Juliana, spoke O’odham and never went to school. He worked on cotton farms and on ranches, supporting his wife and eight children.

Zepeda was the middle child in her family, attending elementary and junior high in Stanfield, and then went on to Casa Grande Union High School, graduating in 1972.

She was a bookworm in school and her senior year she enrolled in a preparatory program for minority students through Arizona State University, spending the summer after high school on the ASU campus. Once the program was completed, she enrolled at Central Arizona College in Coolidge and received her associate of arts degree in general studies, and then enrolled in classes for social work for one year before transferring to the UA and majoring in sociology.

Zepeda found her niche as an undergraduate because the university was creating a linguistics department under professor Kenneth Hale, a visiting professor from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Hale was known for the study and preservation of endangered languages. O’odham was Zepeda’s first language and she longed to read and write the language.

She said there were two books in O’odham that were published, and anthropology professor Dan Matson of the Arizona State Museum took Zepeda under his wing and taught her to read and write her native tongue. The university received funding to teach Indigenous to speak their native language, and Zepeda changed her major to linguistics and received a bachelor’s in 1979, followed by a masters and a doctorate.

Zepeda’s mother died in 1976, three years before Zepeda received her bachelor’s.

“My mother didn’t express to me that she was proud of my achievements, but I know she was,” Zepeda said. Her father, who died in the 1990s, would ask his daughter how she was doing in school. This went on for years. When she graduated, he was happy that his daughter had a job. Zepeda was hired by the UA in 1985 as a research associate in the American Indian Studies program.

Zepeda climbed at the UA — becoming an assistant professor, associate professor and full professor teaching for the department of linguistics. She created an elementary course on the Tohono O’odham language, and a general course on Native American languages mostly of the United States. Her most recent course is teaching language revitalization and language documentation.

She is a recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship for her work in American Indian language education and recovery for tribal communities who have few members who speak their language. She also is a member of the International Task Force for the UNESCO International Decade (2022-2032) of Indigenous languages representing Indigenous people of the United States.

“My early work was working with language teachers who were able to teach the language in the schools and they are still doing it. I worked with teachers on campus and on the reservation, primarily at the schools where they teach,” said Zepeda, mentioning schools in the Baboquivari Unified School District. She also mentioned schools in the Bureau of Indian Education.

“We are in a good position now because we have O’odham teachers who are speakers of the language and can teach the language to students,” Zepeda said. She said the UA’s language institute has been attended by “many O’odham educators who are developing the language in their communities.”

“I have been teaching for 35 years. Dozens of educators who speak O’odham have been impacted,” said Zepeda, who as an adult realized the beauty of the O’odham language. She saw the beauty in the language’s structure, sound and melody. “You have to step back and look at it and you see all these things that are present in your language. You have a different type of appreciation for it,” she said.

Tohono O’odham poet Ofelia Zepeda is an author, regents professor of linguistics at the University of Arizona and director of the UA American Indian Language Development Institute. Video by Carmen Duarte / Arizona Daily Star.