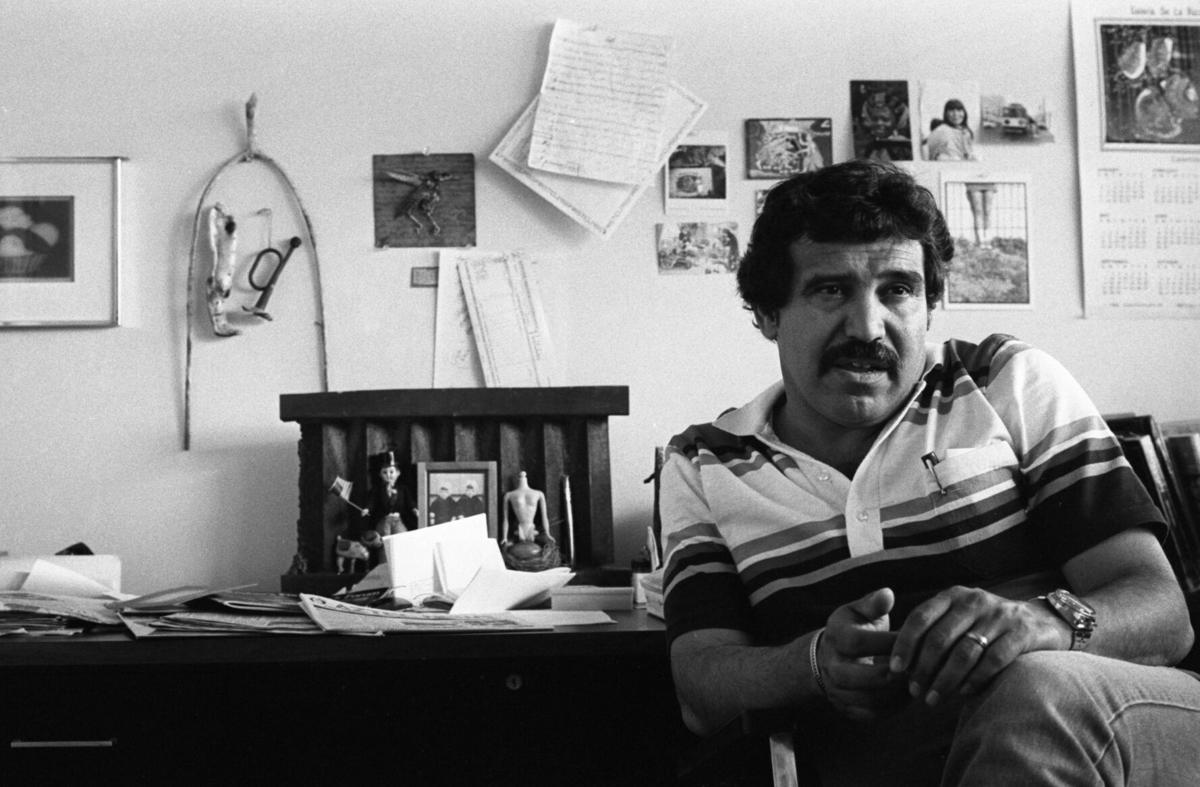

Nine-year-old Lisa Bernal Brethour accompanied her father, Louis Carlos Bernal, as he knocked on strangers’ doors in Douglas in the late 1970s.

They were often invited in. Bernal was quite charismatic and charming, she says.

The late photographer would emerge with captivating, revealing, deeply personal environmental portraits of everyday life in the barrio. Brethour says she, and more often her sister, Katrina Bernal, joined their father to help build trust with potential subjects to create photographs that chronicled barrio life in the Southwest.

Bernal’s photographs speak to the soul of the culture, Brethour says.

The community will be reintroduced to Bernal and have a fresh, in-depth chance to experience and explore his evocative documentary work because the University of Arizona’s Center for Creative Photography received a $255,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation. The grant will fund a substantial exhibition in fall 2023 of Bernal’s work.

With the grant, the Center for Creative Photography aims to raise awareness of the significant Chicanx photographer, promote dialogue and reinvigorate recognition of his photographs, according to Anne Breckenridge Barrett, director of the center and associate vice president for the arts at the University of Arizona.

"Martinez Brothers in Candy Store," photographed in Douglas, Arizona, in 1978, by Louis Carlos Bernal. Bernal took what could have been the subject of snapshots and elevated the content and impact with artistic treatment.

The Center for Creative Photography selected curator and writer Elizabeth Ferrer as the exhibition’s guest curator, says Rebecca Senf, the CCP chief curator.

Ferrer is the author of the 2021 “Latinx Photography in the United States: A Visual History,” the first survey of Latin American photography.

“Perhaps the first Chicanx individual to envision photography as an art form is Louis Carlos Bernal, … who may rightly be called the father of Chicanx photograph,” Ferrer says.

“It’s great timing,” says Brethour, who lives in Tempe. She is excited that the center received the grant near what would have been her father’s 80th birthday.

Bernal’s photographs documented what was valued in the community, such as family and relationships, say Breckenridge Barrett and Senf.

“My images speak of the religious and family ties I have experienced as a Chicano,” Bernal said in a passage that Ferrer cited in “Latinx Photography.” “I have concerned myself with the mysticism of the Southwest and the strength of the spiritual and cultural values of the barrio. These images are for the people I have photographed,” he continued.

Bernal was born Aug. 18, 1941, in Douglas, which is about 120 miles southeast of Tucson on the border with Mexico. He grew up in Phoenix and began taking photographs when he was 11.

“Dos Mujeres,” in Douglas, Arizona, in 1978, by Louis Carlos Bernal. The community will be reintroduced to Bernal’s work in a new exhibition.

He completed his Master of Fine Arts at Arizona State University in 1972 and joined the faculty of Pima Community College, where he founded, headed and taught in its photography program.

Bernal was riding his bicycle on his way to the college’s West Campus in October 1989 when he was struck by a car and was left in a coma. He remained in a coma and died almost four years later on his birthday in his Tucson barrio home.

Powerful pull

No one else was doing the type of work Bernal was — walking the streets and into homes with a camera slung over his shoulder, says Ann Simmons-Myers, Bernal’s successor as head of Pima’s photography program. Simmons-Myers spearheaded the 2002 dedication of the Louis Carlos Bernal Gallery, in the PCC Center for the Arts complex on its West Campus, and created several Bernal exhibitions.

Bernal’s images have a powerful pull that resonates with viewers, says Senf. Bernal took what could have been the subject of snapshots and elevated the content and impact with artistic treatment.

His images shot from the streets and homes of barrios in places such as El Paso and Douglas show subjects who are at ease with the photographer.

Bernal was “charming, engaging and had the ability to make you feel important,” says Simmons-Myers.

When you look at Bernal’s intimate, personal shots, you can see that a “person with a big heart was behind the picture,” says Terry Etherton, owner of the internationally respected Etherton Gallery.

"El Gato," photographed in Canutillo, New Mexico, in 1979, is among the many works by Louis Carlos Bernal that showcase barrio life in the Southwest.

Bernal photographed the objects that surrounded people, says Brethour, who was an engineering student at the time of her father’s accident. She is now an artist who creates sculptural and functional pieces from clay and teaches ceramics and art classes.

As an example of his photographic treatment of everyday items, Brethour points to Bernal’s 1977 “Benitez Suite,” a series of black-and-white images that Ferrer says “poetically documented the home and belongings of a woman who had gone to live in a nursing home.”

Bernal created striking, sentimental, artistic images of everyday items such as holy cards, notes above a bureau and light filtering through a lace curtain.

Bernal was not prolific, says Etherton. He was technically exacting and a harsh critic of his own work. Bernal was one of the first people Etherton met in Tucson. Bernal encouraged Etherton’s gallery and helped Etherton paint the retail space on Sixth Street near Fourth Avenue when he first opened his gallery in 1981.

Bernal was a big part of the reason Etherton came to Tucson.

Spark discussion

Bernal died at a time in a photographer’s career he would have been having exhibitions and writing books, actions which heighten awareness of an artist’s work, says Senf.

The Center for Creative Photography acquired a sizable addition to its Bernal holdings in 2014, says Breckenridge Barrett. The funding will enable the center to celebrate and commemorate the Bernal collection. The collection includes 98 fine prints, both black-and-white and color, and research materials, such as project records, correspondence, clippings, writings and publications.

The center is taking an interdisciplinary approach to the project and is forming a community advisory group to help define and create relevant, authentic programming.

Guest curator Ferrer’s knowledge allows her to draw on a range of ideas, themes, historical considerations, art historical trends and medium-specific developments, says Senf. Ferrer will be working from the primary source material in the Center for Creative Photography collection, directly studying the prints, negatives and other archival materials Bernal produced. She will also interview Bernal’s students and colleagues.

Louis Carlos Bernal photographed Leon Speer's Barber Shop, Felix Valdivezo and daughter Patricia, in Lordsburg, New Mexico, in 1978. Bernal's photos often documented what was valued in communities, like family and relationships.

Breckenridge Barrett and Senf say the Center for Creative Photography aims to create conversation and expect new scholarship to percolate from the exhibition and programming.

The Luce-funded project to make better known Bernal’s artful documentation of the Mexican-American experience is an example of Arizona Arts’ commitment to the principle that our location in the Sonoran Desert is a rich context for rigorous engagement with the arts, said Andrew Schulz, UA vice president for the arts, in a news release.

Arizona Arts is the overarching UA division for academic programs of the College of Fine Arts and the arts and entertainment experiences UA produces and curates.