Editor's note: This story was originally published in 2021.

Día de los Muertos, also known as Day of the Dead, has been a long-celebrated holiday in Mexico and parts of the United States on Nov. 1 and 2.

But what exactly is Día de los Muertos? #ThisIsTucson chatted with Michelle Téllez, Ph.D., an associate professor and director of graduate studies for the Mexican American Studies department at the University of Arizona. This explainer will cover the origins of the holiday, its traditions and what it means to the Tucson community.

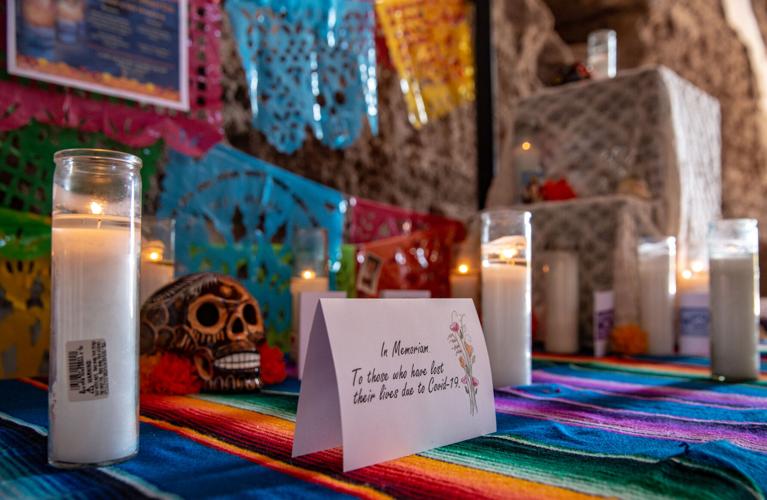

A Día de los Muertos altar inside the Mission San José de Tumacácori at the Tumacácori National Historical Park, on Oct. 21, 2020.

A holiday 3,000 years in the making

The origins of Día de los Muertos can be traced back 3,000 years, where the Aztecs held a ritual known as Miccaihuitl that honored the dead and celebrated the changing of the seasons, including the harvesting season. As a result, the holiday is “deeply related to the natural world,” according to Téllez. Once the Spanish arrived in the Americas in the 16th century, they brought organized religions, such as Christianity and Catholicism, to the area.

“Upon the arrival of the Spanish and Christianity, they were looking for ways to further assimilate Indigenous peoples,” said Téllez. “And so they brought in All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, as a way to syncretize the ancient ceremonies of Miccaihuitl.”

Now, Día de los Muertos is a combination of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, and honors our ancestors and celebrates the lives of loved ones who have passed before us.

“I think in this moment in time, as people become more aware of what Day of the Dead is and the possibilities that it represents, people are yearning for a way to connect. Both to their ancestors, to their family, community members, the natural world, to ceremony, to traditions, to rituals, to have a way to understand themselves in relationship to what is coming for all of us,” Téllez said.

An ofrenda at St. Philip's Plaza. -- Credit: Sue Agnew

The traditions of Día de los Muertos

In Mexico, one of the most significant traditions for Día de los Muertos is to visit your deceased loved ones at the cemetery, clean off their grave and decorate it with bright orange Mexican marigolds and items that they enjoyed.

You can also create an altar, also called an ofrenda, in your home if you are unable to visit your loved ones at the cemetery. An altar is usually filled with photos of the deceased, a food offering such as pan de muerto and other items such as candles, flowers and papel picado.

However, there is no right or wrong way to create an altar that best represents your deceased loved ones. Téllez says there’s a spectrum to decorate an altar that best fits your beliefs. Some may incorporate items representing the four elements — fire, water, wind and earth — while others may include more religious items representing the Virgin Mary or Jesus Christ.

“It's just important to be clear that there's a spectrum on how altars are created and how people, sort of, ground their altars might be a tad different between communities and families and people, but I think the sentiment is the same,” she said.

The altar serves as a portal to welcome the spirits of your deceased loved ones back into your home on the nights of Nov. 1-2.

Other traditions include throwing a party or hosting neighborhood altar gatherings. In Tucson, the local nonprofit organization Many Mouths One Stomach hosts the 2-mile All Souls Procession annually. This year, the All Souls Procession to honor deceased family, friends and community members will be held on Sunday, Nov. 5.

Monica Smith, right, shows Roberta Carrillo the ofrenda, or altar, with members of her family at the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson, on Oct. 23, 2018. Smith and seven members of the Carrillo family worked to get their Dia de los Muertos altars ready for display.

It’s not related to Halloween

Although Día de los Muertos is right after Halloween, it’s not related. Many people associate these holidays with one another because of Día de los Muertos’ newer tradition, painting a calavera, also known as a sugar skull, on one’s face.

However, the calavera face paintings aren’t a costume.

“People want to embody the duality of life and death by painting their faces and I think some people really are drawn to that and other people reject it as not being traditional,” Téllez said.

Over the years, Día de los Muertos has become something more of a commercialized holiday in the United States instead of remaining a cultural-based holiday.

“It becomes something that people want to sell and buy and that, for me, is the most problematic thing. Because culture shouldn't be bought and sold,” she said.

Frank Perez and his fiancee, Donita Montgomery, remember departed friends and relatives as they walk in the 30th annual All Souls Procession in Tucson in 2019.

Día de los Muertos in Tucson

The All Souls Procession has been a Tucson tradition since 1990 and brings around 150,000 participants to the annual event.

If you can’t make it to the procession, there are plenty of other ways to celebrate Día de los Muertos in Tucson.

Check out local panaderias (bakeries) who are baking up pan de muerto or build your own altar in your home to celebrate the lives of your ancestors and loved ones in private. You can also find ofrendas at community spaces around town too, such as the Presidio Museum and the MSA Annex.

A look at the 2022 community altar at the MSA Annex, 267 S. Avenida del Convento.

There is no “wrong way” to honor your loved ones, but Téllez hopes that the community will continue to learn more about the holiday and its origins to help avoid the “commodification and capitalization” of it.

However you choose to celebrate, don’t forget the cultural roots behind the holiday.

“The visibility of Día de los Muertos in Tucson allows for the continuation of a cultural practice that I think is really important,” Téllez said. “And allows young people and community members to see themselves in that tradition.”