Typically, the ongoing work of archeologists is relatively obscure — familiar to others within their circles, and unseen by the rest of us. That changes a bit when a Presidential administration takes it upon itself to blast, bulldoze, and desecrate Native American sites and drain centuries-old water sources.

Those types of actions will get the attention of the Washington Post, National Public Radio, the Sierra Club, and even the Supreme Court.

In early 2020, Sandy and Rick Martynec of Ajo got such attention. The construction of Donald Trump’s “big, beautiful wall” posed a threat to their archaeological work along the U.S.-Mexico border, as well as the region’s vegetation, natural resources, and wildlife.

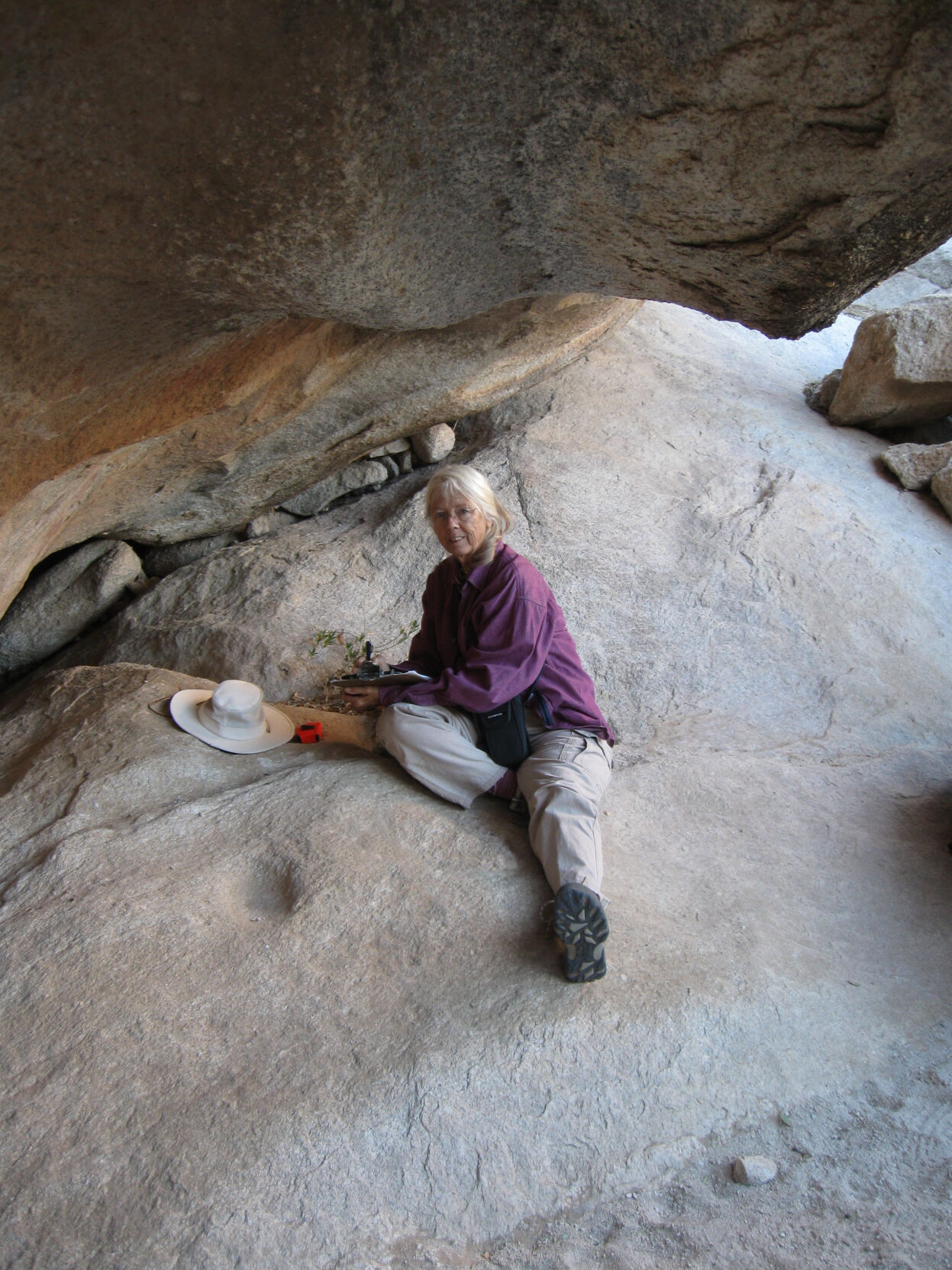

Garnering attention from the press is generally not their style. Retired archeologists, the Martynecs have been volunteering their time since 1996, documenting human life along the border — in the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and Organ Pipe National Monument where they protect artifacts and sites, rather than expose them to prying eyes or looting hands.

Back in the 1990s, when they were wrapping up a paid project on a border road project, a manager from Cabeza Prieta approached them and played “coyote calling out the dogs,” said Rick.

“Don’t you wonder where all these trails [off the road] go?” the manager asked.

They did. And, moreover, “What were they doing? What were their food?”

They were hooked, and made an arrangement to do a supported, but unpaid, archeological survey of Cabeza Prieta.

Sandy and Rick, both 75, have documented over 600 features or sites that record human habitation in the area ranging from 10,000-year-old Paleo-Indian, through 16th-century European and 18th-century O’odham farming settlements.

They’ve been particularly interested in how the desert O’odham and their ancestors managed to make treks across the desert on foot, — from the Salt Pilgrimages to the Sea of Cortez; to the Yuma area to farm; and how they managed to conduct trade, as evidenced by seashells used for jewelry and obsidian for arrowheads.

Their survey is complete, but now they’re seeing “connections.”

Naturalist and writer Bill Broyles notes about the Martynecs, “Without their work, much information would already be lost to erosion and vandalism. Because of their work, sites are better protected, and we all — archeologists, site stewards, and public alike — have a better understanding of who, when, and how prehistoric and subsequent people lived there.”

In their 25 years, Broyles said, the Martynecs “by themselves or leading strong volunteer crews of dedicated desert detectives, have studied hundreds of archeological villages, camps and trails in Southwestern Arizona. They have filled in the blanks of major sites such as Las Playas, Charlie Bell Canyon, and Montreal Well.”

But they have also witnessed degradation and destruction inflicted on the area. Looters and vandals have long been a threat to archeological sites.

An even greater threat in recent years was the militarization of the border by the U.S. Government.

Cross-border foot traffic has long cut trails through the desert, but since 9/11, Border Patrol vehicles have carved roads and damaged the environment and archeological sites.

Rick tells a story that demonstrates how “national security” doesn’t necessarily equate to archeological destruction: During the George W. Bush administration, when efforts were made to bolster the already-existing fencing between the United States and Mexico, contractors were poised to bulldoze the 60-foot wide “Roosevelt Reservation” roadway. The Martynecs realized it might also destroy the ancient Las Playas Intaglio they had uncovered.

In Cabeza Prieta, the intaglio is an 84- by 15- meter fish-shaped figure tamped into the ground. The Martynecs wanted it preserved, so they recruited some friends and set about encircling it with small rocks, along with an adjacent gravesite that would definitely encroach on Roosevelt.

The construction supervisor arrived and demanded to know what they were doing. They explained, and he left. When he returned, he was accompanied by a crew. To the Martynecs’ surprise and delight, the contractor ordered large boulders to be arranged around the site to protect it. In addition, they diverted the road fifteen feet, to secure the grave.

Those sorts of actions were not taken during the Trump years.

When the contractors rushed in to build Trump’s 30-foot steel “wall,” they banned anyone like the Martynecs from approaching within a half-mile. They scraped bare the desert, killing 100-year-old “protected” saguaros, bulldozed earth into stream beds, and began sucking up enormous amounts of ground water for its concrete bases.

Quitobaquito, a seep- and spring oasis that’s been used for at least 16,000 years, is only 200 feet from the border, and was particularly vulnerable.

Biden stopped construction just in time, Rick observed; they’d planned illuminate the wall with stadium lights. “You’d have been able to see them out in space.”

The Martynecs noticed subtle improvements since construction was halted. Ground water has ceased subsiding. Thanks to actions taken by Tohono O’odham Tribal Chairman Ned Norris, Jr., destruction of Monument Hill, where bodies of warring Apaches had been left, was halted.

The Martynecs’ influence is far-reaching. Rich Davis, archeology advisor to the Methow Field Institute, who, along with his wife Linda, volunteered with the Martynecs for years, praised Sandy and Rick for their own pursuit of archeology. “They inspired many of us to become better, more dedicated people through their example,” Davis writes, “and through their professional high standards in fieldwork and reporting….No long hike, no cold desert nights, hot days, no fear of drug smuggling encounters prevented them leading us to the next discoveries.”

What still remains the greatest threat to our vulnerable, ephemeral archeological connection with the past? “People not understanding,” Sandy Martynec said. “People just not understanding.”